Culture of Abkhazia

From the earliest of times, a distinctive culture began evolving in Abkhazia. The warmth and mildness of the climate and the fertility of the land had defined the Abkhaz way of life. Thus, the ancient Abkhaz were mainly preoccupied with farming, cattle breeding, hunting, fishing and handicrafts. While defending their land from enemy attacks or fighting wars, the Abkhaz also developed combat and weapon-making skills.

Abkhazian culture is based on a folk ethical principle called apsuara, which means "being Abkhazian". Professor Sh. D. Inal-Ipa, a well-known Abkhazian ethnologist, defines apsuara as a traditionally shaped way of expressing the national conscience, an unwritten code of ethnic lore that describes the Abkhaz people's entire system of customs, beliefs and principles.

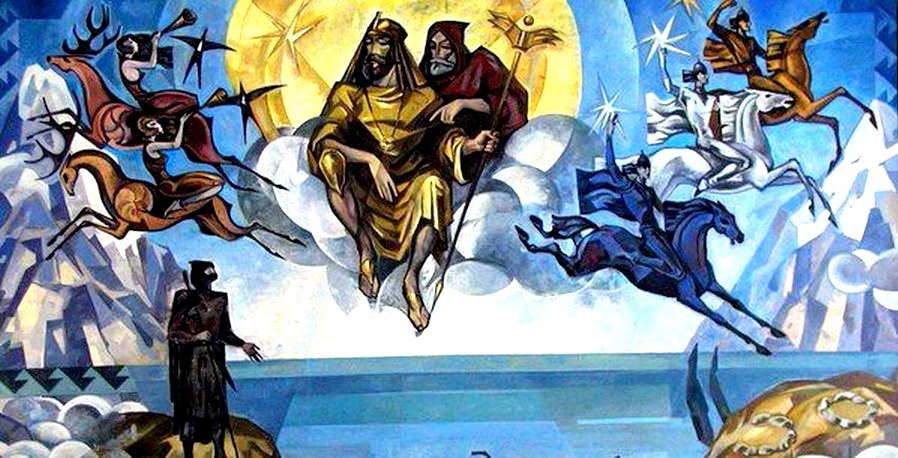

Abkhaz sagas and legends demonstrate the people's archaic beliefs about the Creation of the World and the role of the gods. Abkhaz Nartic sagas tell the story of the life and heroic deeds of the Narts, a hundred brothers and their mother, Satanaya-Guasha.

Abkhaz Language and Literature

Abkhaz is the official language of the Republic of Abkhazia. Together with Abaza, the Circassian languages (Adyghe and Kabardian), and the now extinct Ubykh, it belongs to the Abkhaz-Adyghe group, which today encompasses several million people.

As the common Abkhaz language was being formed, several dialects developed due to the feudal division of the country.

In 1862, P. K. Uslar, a linguist and researcher of Caucasian culture, published a work on Abkhaz grammar and created the Abkhaz alphabet based on the Russian Cyrillic script. D. I. Gulia, considered to be the founding father of Abkhaz fiction and the creator of the Abkhaz literary language, published the first lyrical epic poem in Abkhaz in 1913.

Abkhaz literary language evolved actively during Soviet time, as the language of the nation underwent a formative stage. Over a relatively short time, the vocabulary of the written language expanded greatly by borrowing from the native dialects and foreign languages.

As time went on and the use of written Abkhaz widened, a variety of writing styles developed: business writing, scientific writing, journalistic writing, and above all literary language, the language of fiction. Traditional Abkhaz oral poetic narrative played an enormous role in the formation and evolution of the Abkhaz literary language, as did works by Abkhaz writers, poets and playwrights, such as Dmitry Gulia, Samson Chanba, Iua Kogonia, Bagrat Shinkuba, Ivan Papaskiri, and Alexei Gogua.

Abkhaz Folklore

Abkhazian culture is rich with folk poetry and songs, dance and music. Abkhazian folk songs are a combination of vocal melody and chanting. Ancient pagan songs survive to this day, along with work songs, ritual songs, fairy tales, legends, myths, sagas, sayings and proverbs.

Polyphony is a distinctive trait of Abkhazian folk singing. Usually a tenor will start the song, and the other singers will then join in, improvising around the original melody in a lower register. A curious fact: there is no folk singing done by women, except for lullabies and mourning songs. The oldest songs belong to the hunting and herding folklore; more recent ones celebrate particular folk heroes: Khadzharat Kahba, Saluman Bgazhba and others. There is a widely known series of ritual songs performed to ease the suffering of the wounded. Abkhaz traditional mourning and circle dance songs are very expressive, and traditional weddings include a theatrical performance accompanied with songs and dance for the occasion.

The most significant examples of Abkhaz epos are the ancient sagas about the Narts and about Abrskil, the Abkhazian Prometheus who had fought the gods.

Nartic sagas are typical for most North Caucasian peoples, with the Abkhaz version of the story being the most archaic, in the opinion of many scientists. The sagas tell of a hundred brothers and their beautiful sister Gunda, and their life as governed by their mother, a wise, eternally young woman called Satanaya-Guasha. The sagas center on the youngest brother, Sasrykva. His many adventures and heroic deeds serve as the plot of the epos.

The tales of Abrskil are of later origin. As punishment for disobeying the gods, the heroic Abrskil was chained to a pole deep in the Otap cave, now known as Abrskil cave, in the Ochamchira region.

Music and Dance

Traditional Abkhazian musical instruments include strings, woodwinds, and percussion. Among the most popular string instruments is the ap'hyartsa, a two-stringed instrument with a narrow spindle-shaped frame, played with a bow and usually carved from alder wood. The ayumaa is a triangular harp with 14 horsehair strings (ayumaa means "two-handed" because the musician holds it on one knee while playing with both hands).

The woodwinds include the acharpyn, a flute with three or sometimes six holes made of hogweed (acharpyn in Abkhaz) and adorned with ornamental decoration. Another popular instrument is the abyk, a single-reed horn carved from wingnut wood. The akabak khtsvy, a shepherd's pipe with three openings, is carved from a pumpkin stem.

Percussion includes various types of drums and clappers (also used to scare birds away from corn fields). Akyapkyap clappers consist of a thick handle with attached wooden slats that make a loud crackling noise when rotated, and the very popular adaul drum often serves as the main musical accompaniment, especially for folk dances.

Dancing is the most popular form of folk performance in Abkhazia. There are several professional dance troupes in the country and several choreography studios for children. The troupes perform folk dances, ritual dances with daggers and burkas (traditional coats with high, squared-off shoulders), and other traditional Caucasian dances.

Clothing

Traditional clothes are an important element of Abkhazian culture. In the past, people dressed in accordance with their occupation, and divided their clothes into everyday clothing, clothes for festive occasions, and ritual dress.

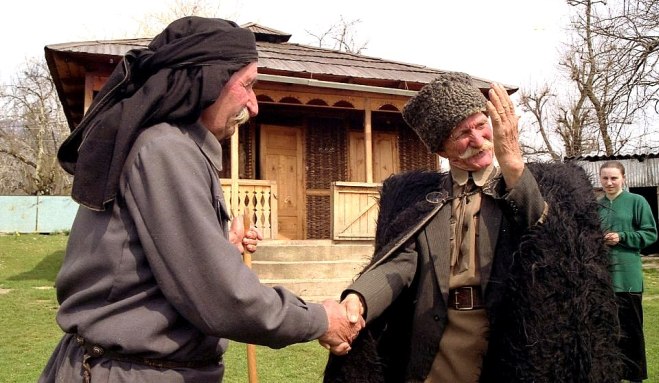

The chokha (or cherkeska) is the oldest and, even to this day, the most popular article of traditional male clothing. It was traditionally worn with trousers, a shirt with a button-up collar and a pair of rawhide shoes or, for special occasions, custom-decorated goatskin shoes. Spats or felt stockings were worn over the calves, and knee pads over the knees. The curiously shaped bashlyk served as the traditional men's head gear.

A must-have for every Abkhaz horseman was the burka (auapa in Abkhaz), a long cape with high square shoulders that was made of shaggy felt and made the silhouette look almost regal.

The traditional women's costume consisted of several key items: a dress with a short or long tunic coat worn over it, a shirt, two underskirts, a pair of trousers, and a hat or a head scarf. A decorative sash, worn around the waist on top of all the layers, was often a genuine work of art. The short tunic coat was usually made of homespun broadcloth or velvet; it fit tightly in the chest area and widened below the waist.

The alabasha, a tough wooden staff with a metal foot and a hook on top, was a symbolic element of traditional appearance. A walking stick that doubled as the simplest weapon, it would also serve as a sort of a "soap box" for someone about to make a speech: if an elder dug his staff into the ground and leaned on it, it was a sign that he was about to speak.