The Eden of the Caucasus | Colonial Politics, 20 July 1899, p.2

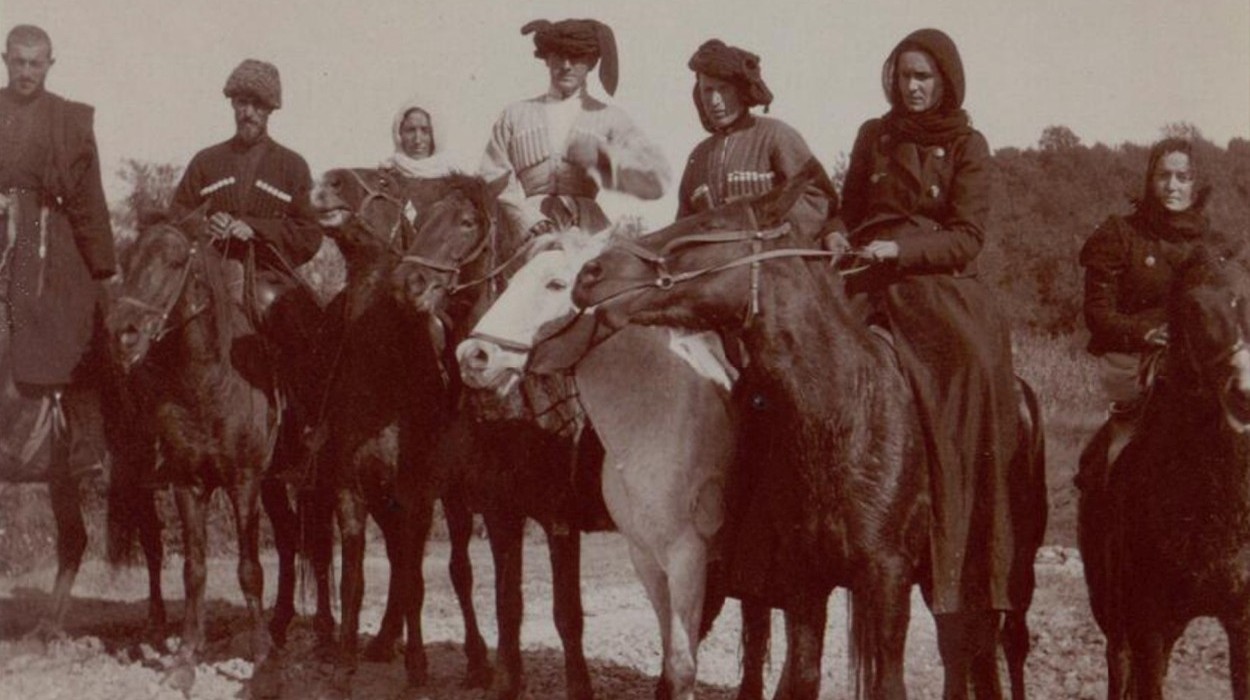

Abkhazians (1903). Photo by Joseph de Baye (1853-1931), French archaeologist and traveller.

Translation:

We extract from the interesting volume that Mr. Jean Carol has just published on two journeys - to the Caucasus - the following chapter on the Abkhazian people:

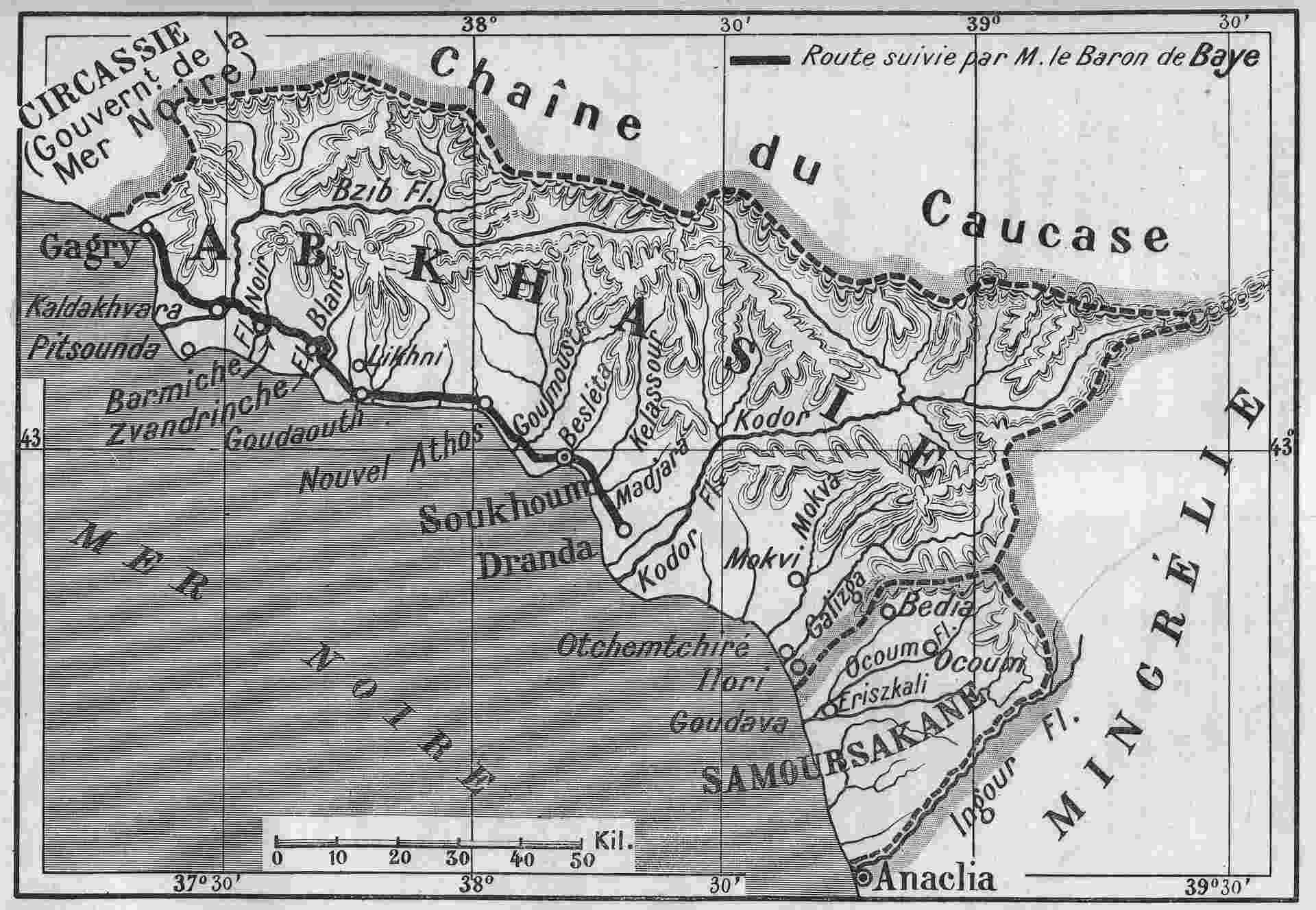

... Here we are in Sukhum. The central chain, from this point, moves away from the sea and continues its path diagonally across the Ponto-Caspian isthmus as far as the Apsheron peninsula, where it ends in a spewing of mud and naphtha. We are in the land of the Abkhazian people.

Of all the indigenous people I have encountered on my travels, the Abkhazians seemed the most amusing to me.

On the day of my arrival in Sukhum, I saw, in the public garden, two Caucasians whose careful attire indicated a certain ease of status. They were young, powerful, and lively. For an hour, they smoked and chatted, sitting on a bench. A phaeton came by. (Our uncovered two-seater cab, with a folding seat, has made its appearance in Turkey and in the Turkish cities of the Caucasus in recent years, where it is unanimously, though improperly, called a phaeton.) These individuals hailed the driver, got into the carriage, and had themselves transported to a café located less than three hundred steps away.

L'Eden du Caucase | La Politique coloniale, 20 juillet 1899 p.2

+ The original French version in PDF can be downloaded by clicking here.

"Here we have people who don't like to tire themselves out," I observed.

"It's because they are Abkhazians," murmured Rostom. "An Abkhazian must be very poor to go on foot. And even then, he will never go very far."

During one of my crossings on the Black Sea, around nine in the morning, while all the passengers, up since dawn, seemed happy to bustle about in a bright and warm atmosphere, my attention was drawn to the rhythm of a happy snore. This noise came from the nostrils of a very handsome man, stretched out on a kind of improvised bed on the lower deck. A heap of rich rags, bourkas, carpets, and scarves furnished him with a wide and soft bed. Another brightly coloured carpet, hanging down on each side, served as a blanket. One could see the edge of a linen sheet that had been carefully spread under his unclothed body; and his brown head, marked by brown eyebrows that one might have taken for a flight of swallows, with a double termination – one being his black beard and the other being his fur cap - sunk into a deep pillow. At the foot of this opulent-looking makeshift bed, a few valuable weapons were negligently deposited. A second pillow still bore the imprint of a head that had spent the night next to that of the handsome sleeper, and a young woman seemed to be watching over this restorative sleep with solicitude.

"Who is this oriental prince amusing himself by travelling in third class?" I asked.

"He's a wealthy Abkhazian," said the captain disdainfully. "They're all the same. Lazy as snakes. And they just can’t be bothered..."

"Even when travelling. It would seem."

But navigation in the Black Sea is no strait-laced matter.

On a Sunday, not far from the New Athos monastery, I witnessed a match between two groups of horsemen as remarkable for the solidity of their attire as for the fanciful nature of their exercises. One could guess that these men spent half their lives on horseback. One could understand, from the intoxication of their expressions, that they had no greater pleasure. And indeed, they were Abkhazians. The Abkhazians are the centaurs of this fabulous land. I found myself in the heart of their country, in the part where Christianity dominates. Below Sukhum, the former capital of the principality, the Abkhazian people - who call themselves Absoua, meaning, modestly, ‘the People’ par excellence - generally profess the religion of Muhammad. Christians or Muslims, their dominant passion is the horse. They are no less adored by their women, upon whom all the arduous or coarse tasks fall.

Abkhazia Map by Joseph de Baye (1853-1931), French archaeologist and traveller. Between 1898-1899, he visited the Caucasus. He wrote a book about Abkhazia: "En Abkhasie: Souvenirs d'une mission" (Paris, 1904).

+ Abkhazia and the Abkhazians (1903) | Photos by Joseph de Baye

+ The Universal Geography: The Earth and Its Inhabitants - Vol. VI Chapter II [The Caucasus], by Élisée Reclus

‘Ah! What an unpleasant people,’ you say? Can one lack gallantry and pity for the weaker sex to such an extent! It is clear that we are in the East!

There is no need to go to the East to find what revolts you. In Vienna, the European city where people claim to be the most gallant, the hard labour of masonry is exclusively reserved for women. And it is indeed one of the things that shocked me the most in this pretentious capital, along with the false luxury of its plaster palaces...

Let us complete the sketch of our Abkhazians with two essential traits that, at first glance, seem to exclude each other: they are thieves and they are hospitable. But even here, there are nuances, which for us are subtle ones. Thieves of horses, instruments, weapons, belongings, and generally anything of value, yes. But a thief of money, never! That would be a disgrace, an infamy. The father would ruthlessly chase from the house the son who boasted of having stolen a kopeck. On the other hand, he would approve of his son having acquired by theft scabbards, belts, stirrups, or other objects of this kind, made of a purer metal than the alloy of kopecks. Where does this bizarre respect for money come from in a people who were ignorant of its use before Russian domination? “Among the Abkhazians,” says Elisée Reclus, “the sign of exchange was usually represented by a cow, whose calves were the interest: it happened that after a few years, a small loan had to be repaid by the delivery of an entire herd. It was only in 1867 that this primitive mode of usury was replaced by that practised by all civilised peoples."

Another example. An Abkhazian offers you hospitality, and God knows how conscientiously they practise this virtue! Everything in their house seems to belong to you, however long you stay, and, when you are about to leave, they will beg you to remain their guest for one more day. They have depopulated their poultry-yard and emptied all the wine from their amphoras for you. Your person and belongings have been sacred to them. Then they have escorted you, as is customary, to the border of the neighbouring village. From there on, break off relations with him. If they were to accompany you further, they might try to purloin something from you.

Didn't I say that these nuances escape us? The Abkhazians would probably not understand any better the distinctions we make in the West between high-society thieves and highway-robbers.

Abkhazian villages have retained all their character, but Sukhum, the ‘capital’, now the administrative centre of a military district and seat of an Orthodox bishopric, has little or almost nothing left of the appearance that must have been offered up to 1877 by the Turkish city, where the Ottomans had built a fortress with debris from Greek monuments.

Its vast cove, where the imagination likes to picture the fabled Dioscurias emerging from the waves, is deep and sheltered from the winds. The Bora, the scourge of Novorossijsk and worthy rival of its namesake that blows in Trieste, is unknown here. With little money, one of the best ports in the great ‘Russian lake’ could be adapted here for navigation.

The bulk of local trade consists of dolphin-fishing, which yields an average of 2,500 heads per year. The dolphin is a very decorative fish; nevertheless, it remains the scourge of the Black Sea from the perspective of other species. While the fishermen of Sukhum, equipped accordingly, find some resources in it, it is cursed everywhere else in the coastal fisheries. Incessantly hunted by this voracious predator, the small fish that deserve our esteem and the feasting on which it disputes with us take refuge en masse in the Sea of Azov, which is too narrow and too shallow for the dolphin's frolics.

General view of Sukhum. Early 20th century.

The bourgeois dwellings (can one really use this word in a country where there is only ‘the people’, military personnel, and militarised officials?) in Sukhum resemble those in all the small southern towns of Russia. A ground floor topped with a first floor, pink walls, and a green-painted metal roof. The same goes for the shops, set back under the awning supported by wooden columns at the edge of the pavement. The series of awnings forms narrow and long galleries where people walk, sheltered, their noses in the stores, which are also workshops open to the public's curiosity. Here, the only secret of manufacturing is the manual skill or taste of the worker. Artists, armourers, embroiderers, goldsmiths, as well as shoemakers or bakers, everyone works coram populo. ‘Take-away’ cooking, as it would be called in Paris, or to be consumed on-site, is prepared with the same disdain for secrecy. Borscht foams before your eyes, and you can see a fish cooling in the terrible oil in which it was cooked.

A wide avenue leads to a vermilion church, which is better left unmentioned. The cosmopolitan clientele of a dozen Greek taverns, the cellars where people gather to sing while drinking wine stored in skins, the arrivals and departures of passengers noisier than numerous, all this lends constant animation to the quay. The quay extends south of the city alongside a beautiful public garden, where all these indoor-plants that we keep alive with such difficulty grow freely, facing the warm sea – with, at the slightest swell, the wave hooded on the parapet of the terrace.

As for the landscape, it forms a superb and charming setting. In the coming century, Sukhum could become the Nice of the Caucasus, as Yalta is the Nice of the Crimea. Those plagues by hest-ailments come in search of an effective respite and have these elegances to follow. If we succeed, as can be hoped, in confining the fever far enough around Sukhum through the desiccation of the masses of ferns and the multiplication of eucalyptus-trees, this Asian paradise will be one of the sweetest places on earth.