Samir Khotqo: "The creation of the Circassian flag is connected to the pan-Circassian mission of Sefer-bey Zaneqo"

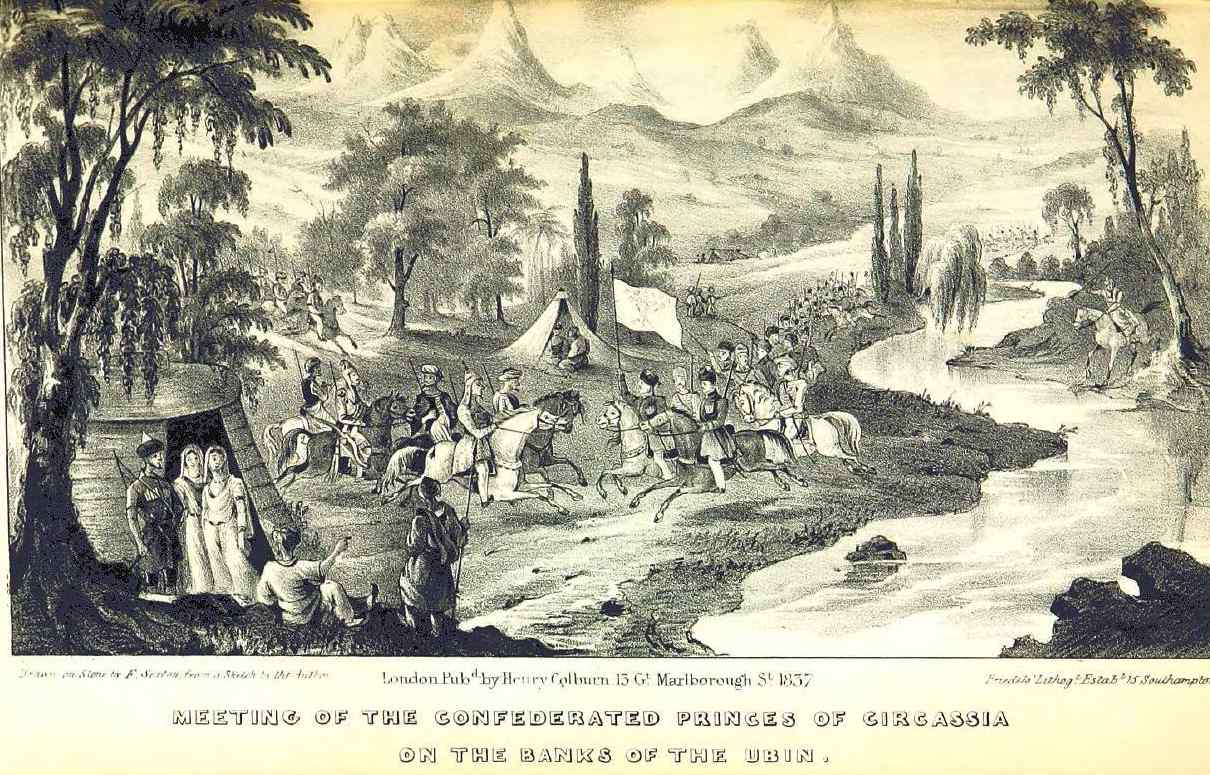

Gathering of the Confederated Princes of Circassia on the Banks of the Ubin in 1836. Drawn by John Bartholomew.

Naima Neflyasheva, Candidate of Historical Sciences, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Civilisational and Regional Studies, Institute for African Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences.

Today, 25 April, marks Circassian Flag Day. The elegant and aesthetically pleasing Circassian (Cherkess) flag serves not only as the national symbol of the Republic of Adyghea but also as the emblem for all Circassians, signifying their transnational spiritual and cultural unity.

Circassian Flag Day is to be numbered among the truly national celebrations, featuring horseback-processions, car-rallies, dzhegu (Circassian dance-gathering – ed.), and online flash-mobs. However, our understanding of the Circassian flag actually remains somewhat limited. Each year, the online sphere is inundated with quotes from the Englishman Edmund Spencer's book, "Travels in Circassia", describing the flag's first appearance in Circassia, as well as multiple interpretations of the Circassian flag's symbols – the 12 stars and the three crossed arrows.

I had a conversation with historian Samir Khotqo, Doctor of Historical Sciences and leading research fellow at ARIGI, about the real creator of the Circassian flag, the heraldic origins of its symbols, and the mission of Prince Sefer Bey Zaneqo [Circassian: Занэкъо Сэфэрбий - ed.] in the Ottoman Empire.

Samir Khotqo, Doctor of Historical Sciences and leading research fellow at ARIGI.

Naima Neflyasheva: In Western academic literature, the idea persists that the creator of the Circassian flag was Englishman [Scottish -ed.] David Urquhart, the secretary of the English embassy in Istanbul. Urquhart is known for a speech in which he refers to the flag of Circassia as the flag of freedom and claims to be its author. Regrettably, this has led to provocative and misleading articles about the supposedly non-Circassian authorship of the flag. Samir – has Urquhart's speech been scrutinised as a historical source? Is his involvement in the "Circassian issue" overstated, given that he visited Circassia only once? How can his claim of authorship be evaluated from a critical standpoint in terms of analysis of sources?

Samir Khotqo: Indeed, historical literature often claims that the Circassian flag was devised by David Urquhart (1805-1877), who began his diplomatic career as one of the most influential political figures of the British Empire. In fact, Urquhart himself emphasised that the authorship and even the idea of creating the flag belonged to him. Historical documents reveal that Urquhart sent three copies of the flag to Circassia in June 1836. One document mentions that Daud-bey, Urquhart's Muslim pseudonym, sent three monochrome flags to the Shapsughs, Natukhays, and Abazins, each featuring a white circle in the middle with three black arrows. According to Urquhart, this was the flag of independence, sent by the English king to the Circassians.

However, relying solely on this information without considering the general historical-political context would oversimplify the situation and overlook one of the influential figures in the national liberation struggle, Sefer-bey Zaneqo. The context is that David Urquhart's only three-day visit to Circassia in 1834, as well as subsequent English-Circassian contacts, were facilitated through Sefer-bey Zaneqo (1789-1859), the authorised Circassian representative in Ottoman Turkey.

It is clear that without the approval of the "Ambassador of Circassia", David Urquhart would not have taken responsibility for such an important matter.

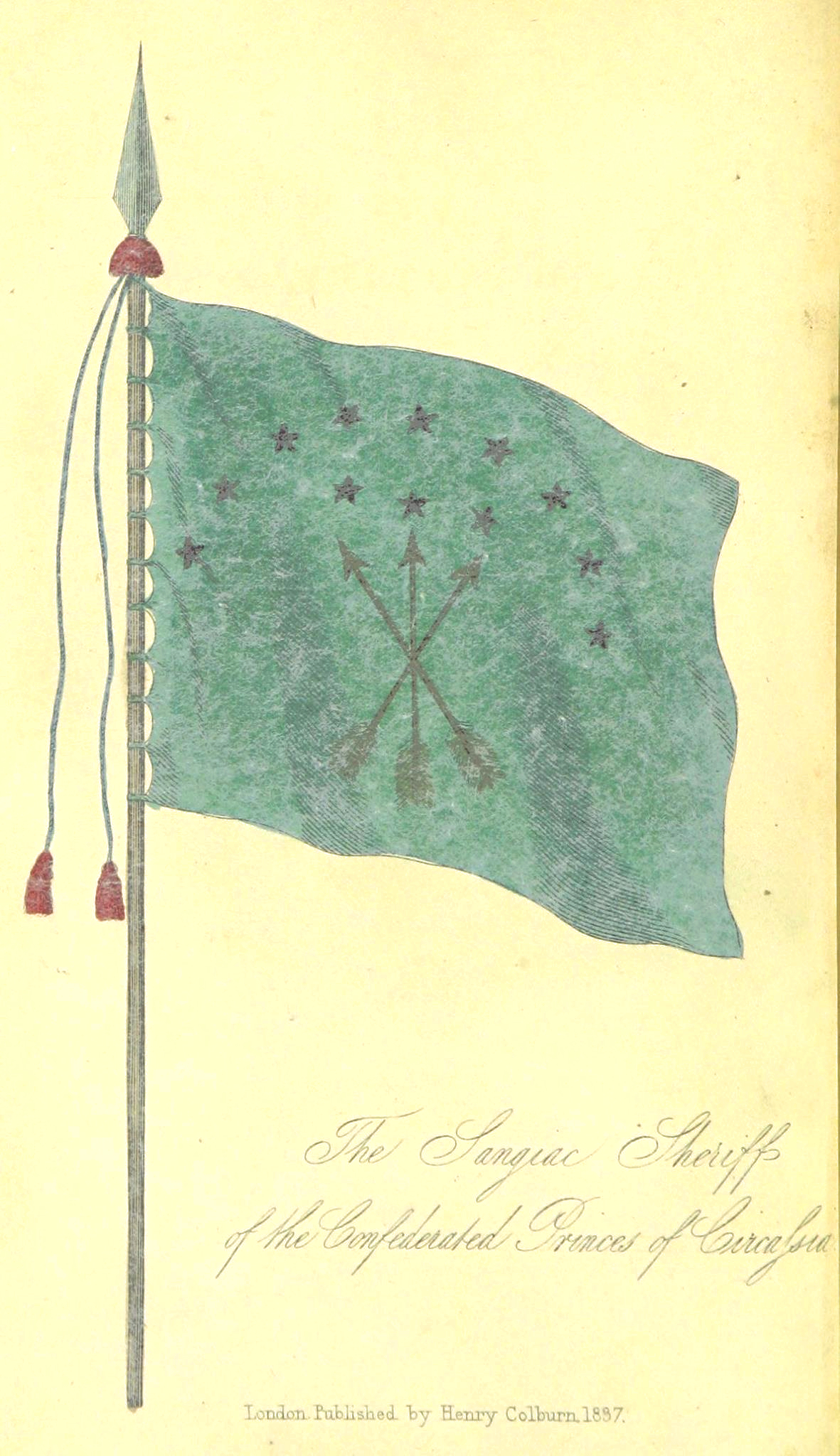

'The Sanjac Sheriff of the Confederated Princes of Circassia' - London, 1837. 'Travels in Circassia, Krim-Tartary, etc." by Edmund Spencer. Vol. II. London, 1838.

+ The Flag of Circassia: Speech of Mr. Urquhart, Glasgow, 23 May 1838 (Diplomacy and commerce, 1840)

+ The Work of J.S. Bell and D. Urquhart in Circassia in the 1830s: Enablement of Communication [PDF]

+ Imagining Circassia: David Urquhart and the Making of North Caucasus Nationalism, by Charles King [PDF]

Naima Neflyasheva: Moreover, the ideological influence of the English should not be overestimated, even though it was one of the factors affecting Circassia's foreign policy situation. In the same Western academic literature, there are insightful observations that the Circassian élite were not naïve, as they assessed the complexity of the geopolitical and strategic contexts in which they were destined to act.

Samir Khotqo: According to another English source, James Bell, the flag was called Sandzhak-Sherif in Circassia, similar to the name of the main flag of the Ottoman Empire. It was brought from Turkey by a young man named Hatazhuk, a close associate of the famous military leader Shurukhuqo Tughuz. The flag was stored in the village of the chief qadi [Turkish: kadı - a Muslim judge or an official in the Ottoman Empire. - ed.] of the Natukhay region, Mekhmet-Effendi. It seems that Sefer Zaneqo was directly involved in the creation of the flag.

Naima Neflyasheva: Edmund Spencer, who provided the most emotional account of the Circassian flag's reception in Circassia in 1836, is extremely concise regarding details as to who was its author, who delivered it, and who stitched it. He states that the first copy of the flag was embroidered by a high-ranking Circassian princess living in Istanbul. How in your estimation can the name "Sandzhak-Sherif" be interpreted? Sandzhak is a word of Turkish origin, whilst Sherif is of Arabic origin.

Samir Khotqo: The name Sandzhak-Sherif signifies "Sacred Banner" or "Banner of the Prophet" (sancak — Turkish ‘banner, province, state’; sherif — Arabic ‘noble, aristocratic’). Konstantin Bazili, a renowned Russian orientalist, wrote: "Sandzhak-Sherif was initially the chalma [‘turban’ - ed.] of one of the Muslim warriors; it then became the first banner of Islamism and the caliphs. It was passed to the Turkish sultans along with the caliphate after Selim I conquered Cairo. It is usually taken out at the camp when the sultan himself or the grand vizier leads the army."

Naima Neflyasheva: The Circassian flag features three arrows and 12 stars, and the interpretations of these symbols grow every year. Some explanations are quite convincing, while others are fantastical. Moving away from speculation and focusing on specifics, are there any genuine symbols in Circassian heraldry that could be traced back to the tradition of depicting arrows and stars on banners?

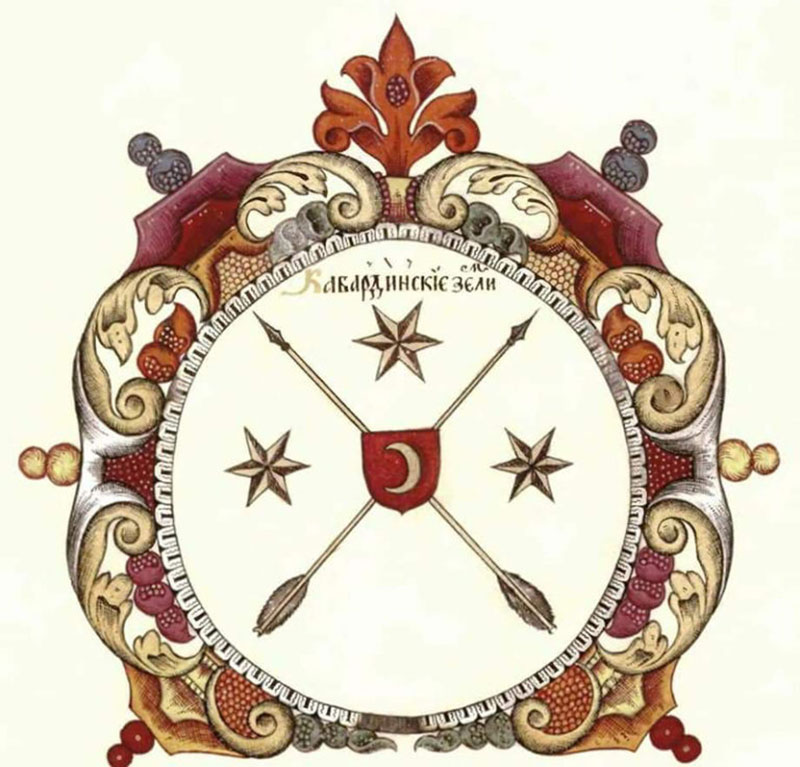

Samir Khotqo: The historical genealogical roots of the Adyghe flag are connected to the banner of the vali (‘senior prince’, pshyshkhwa [Circassian: пщышхуэ -ed.]) of Kabarda, Kuchuk Dzhankhotov. His banner depicted "two crossed arrows pointing upwards, and three stars - a symbol of united Kabarda". In its turn, Dzhankhotov's flag can be traced back to the coat of arms of the "Kabardian Land", created for the "Tsar's Titular Book'' [Ца́рский титуля́рник - ed.] of 1672.

Thus, the Circassian flag, assembled by the Western Adyghe prince Zaneqo in Istanbul (not excluding the participation of D. Urquhart) in 1836, has its origins in the coat of arms of Kabarda, created in Moscow in 1672.

Coat of Arms "Kabardian Land" 1672. See: Russian State Archive of Ancient Acts (RGADA). Fund 135. ANCIENT STORAGE. Inventory unit 401. "Titularnik" 1672.

The contemporary researcher Eugene V. Pchelov suggests that the Turkish coat of arms may have served as a prototype for the Kabardian one. "The basis for this assumption is that Kabarda, like Turkey, was part of the Islamic world. Additionally, since it had considerable independence (and was not included in the composition of the Russian state itself, like the territories of the former Horde of the khanates), it essentially represented the only Muslim land under the supreme protection of the Russian tsars. This fact was reflected in its coat of arms." Pchelov believes that the depiction of crossed arrows could have existed in the Adyghe environment, "including within the family of the Circassian princes, who could have influenced the creation of the Kabardian emblem of the 'Titular Book' to some extent."

Naima Neflyasheva: Since Sefer-bey Zaneqo was related to his father's cousin Atazhuk Khamurzin, the vali of Greater Kabarda, it becomes clear that he was familiar with the Kabardian heraldic tradition. As for the ritual use of arrows, many have written eloquently about this, such as the Adyghe historian and folklorist Shora Nogmov in his "History of the Adyghe People."

Samir Khotqo: Indeed, Sefer-bey Zaneqo could have utilised local genealogical experience when creating the general Circassian flag. Crossed arrows can symbolise the oath of national unity. Shora Nogmov, as you correctly pointed out, wrote that the Adyghes had a tradition of swearing in a sacred place, during which the parties broke an arrow to signify the inviolability of the agreement.

I reiterate that Sefer Zaneqo was the only authorised Circassian leader capable of sanctioning the creation of a flag. James Bell emphasises that Sefer-bey's departure to Istanbul was not for personal reasons but that he had previously travelled around all Circassian regions in the summer and autumn of 1831, securing the support of "chiefs and influential persons".

The Russian ambassador in Turkey, Butenev, emphasised this crucial fact in a letter to Baron Rosen, the commander of the Caucasian Corps: "He had with him written powers, sealed by about 200 highland uzdens [nobles - ed.] and chiefs."

"Meeting of the Confederated Princes of Circassia on the bank of the Ubin" - "Travels in Circassia, Krim-Tartary &c", by Edmund Spencer (1838). p. 270.

Naima Neflyasheva: In one of your articles, Samir, you write that according to Russian sources, the English ambassador Lord Ponsonby negotiated with Prince Sefer-bey in Istanbul not as a private individual but as an authorised "elder of twelve Caucasian tribes for negotiations with the Turkish government and English representatives in the Turkish capital". Are the names of these twelve tribes known?

Samir Khotqo: This is also confirmed by English sources. According to James Bell, "the league, of which Safir-bey was appointed ambassador, consisted of the following twelve provinces: Natukhaj, Shapsugh, Abazakh [Abadzekh/Abzakh – trans.], Psadugh [Bzhedugh - ed.], Temirgoy, Hatukoy, Makhosh, Besni [Bes(le)ney -ed], Bashilbai [a kind of Abkhazian tribe that lived in the Kuban region - ed.], Teberdekh, Braki, and Karachay."

Although Bell does not mention the Kabardians, they were one of the leading forces of the Circassian resistance since a large number (more than 60 auls) migrated from the Kabarda suppressed by Aleksey P. Yermolov to Western Circassia between 1822 and 1825.

The Teberdakh society mentioned by Bell (the "Teberdians [тебердинцы]" of Russian sources) was composed of these Kabardian hadzhirets [refugees or migrants -ed.]. The largest Abaza district, Bashilbai, was represented in this regard (i.e., in granting powers to Sefer Zaneqo) by not only Abaza elders but also Kabardian princes. The Kabardians participated in all Abadzekh gatherings.

It is crucial to note that Sefer-bey perceived the Sandzhak-Sherif as a symbol befitting the given historical context of the Circassians and personally sent copies to his associates in Circassia. For instance, in January 1838, a detachment sent from Anapa captured and burned his twin-masted ship in the harbour of Ozerek, but the Circassians managed to deliver the powder and flag to the Ostagay aul, where Mansur Khawdoqo, an influential member of the Natukhay and Shapsugh Medzhlis [Mezhlis: a council, assembly -ed.], resided.

Therefore, the creation of the Adyghe flag is primarily connected to the pan-Circassian mission of Sefer-bey Zaneqo, and its heraldic origins can be traced back to the history of Circassia, the history of the Circassian princes, and their service within the Russian state.

This interview was first published by Kavkaz Uzel on 25 April 2021 and is translated from Russian.