Abkhazian History in a Nutshell, by Ky Krauthamer

Ky Krauthamer | TOL

Last weekend’s elections saw a familiar crew jostling for the top job in a territory which has thrown off most traces of Georgian control.

If past experience is a useful guide, Raul Khajimba could be in for a hard fight in the deciding round of Abkhazia’s presidential election.

The incumbent leader of the self-declared republic won the most votes in the first round of elections Sunday. In the runoff, which must be held within two weeks, he will face the opposition candidate, Alkhas Kvitsinia.

Only Russia and a handful of other countries recognize the independence of the territory wedged between Georgia and southern Russia. Russia has provided vital investment and military support since Abkhazia broke away from Georgia in the early 1990s.

Squeezed as the country is between two larger states, politics here centers around building an autonomous Abkhazian identity. Voters, however, were frustrated by the lack of concrete policies offered by the 10 candidates in the first round, says Inal Khashig, a writer and editor with the Caucasus news outlet JAMnews.

“The majority either do not know who to vote for or are not going to vote at all,” Khashig said.

They may have been distracted by the drama around the opposition bloc’s original candidate, Aslan Bzhania, who withdrew from the race in July after falling ill from what supporters claimed was a case of poisoning.

Amid demands for his resignation in the wake of Bzhania’s withdrawal, Khajimba accused the opposition of mounting a ploy to seize power, but acceded to its demand that the election be delayed for over a month. Kvitsinia was then chosen as the opposition candidate and presumptive main challenger.

Ethnic Cleansing or Repairing Past Harms?

One thing united the first-round candidates: they all satisfied the authorities of their cultural background. The perceived need to strengthen the Abkhaz sense of identity is felt so strongly that it’s written into basic law. The constitution states that the president shall be “an individual of Abkhaz nationality and a citizen of the Republic of Abkhazia.”

The authorities in Sukhumi have changed course on citizenship rules several times, most recently when a law passed in 2016 permitted only those who can prove they lived in Abkhazia between 1994 and 1999 to be issued a passport. That would exclude most ethnic Georgians, who made up 45 percent of the population until the great majority fled during the independence war of 1992-1993.

Ethnic Georgians were only granted the legal right to return in 1999. Many Georgians, along with Russians and Armenians, complain the current citizenship rules are discriminatory and are not enforced on ethnic Abkhaz, OC Media wrote in February.

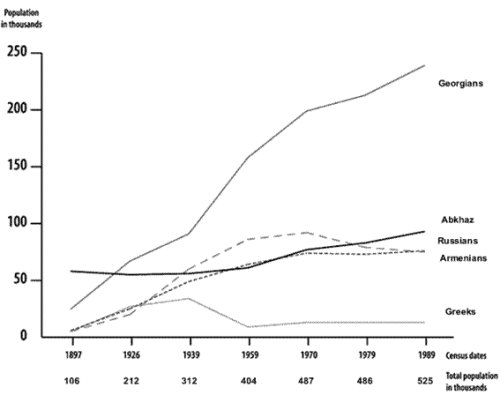

Abkhazia’s ethnic balance has swung back and forth over the last two centuries, almost always for reasons beyond the local population’s control. The Abkhaz were among the hundreds of thousands of Caucasian tribespeople Russia expelled in the 1860s as it seized total control of the region. Estimates of the size of the Abkhaz and Georgian communities in the 19th century vary widely. By the time of the first Soviet census in 1926, Abkhaz made up 28 percent and Georgians 34 percent of the population. The Georgian population rose steadily through immigration both before and after Abkhazia was incorporated into the Soviet Socialist Republic of Georgia, to reach its high of 45 percent in 1989.

Balancing this rapid growth in one segment of the populace, the Abkhaz community shrank, reaching its low of 15 percent in 1959, smaller than either the Russian or Armenian minorities. After the war with Georgia the Abkhaz became the largest single ethnic group in the partly depopulated breakaway territory. They made up just over 50 percent of the population according to the 2011 census.

An Edgy Dependence on Moscow

Echoing the country’s often turbulent past, contemporary politics, although the main actors agree on the basic principle of sovereignty under Russian protection, has at times threatened to descend into conflict.

Khajimba, who came close to gaining the presidency in the early 2000s, achieved it in 2014 when his supporters forced the resignation of the then president. His administration has been marked by frequent clashes with the opposition force Amtsakhara, led by Kvitsinia.

Russia is Abkhazia’s main source of investment and imports, and its sole military ally. Russia operates a military base in Abkhazia, and the head of the Abkhazian general staff is a former Russian major general, who replaced another high-ranking Russian officer in the post last year.

The Kremlin’s influence, however, only reaches so far. Khajimba himself experienced this first hand in 2004, when, in a stunning reversal, he lost the presidential election despite having the clear backing of Vladimir Putin. The country teetered on the edge of crisis until Moscow negotiated a power-sharing agreement: Khajimba agreed to become vice president under the winner of the election, Sergei Bagapsh.

This year, Putin “did not openly express his support,” but his meeting with Khajimba in early August “was seen as a clear message of the Kremlin’s stance on the [election],” JAMnews writes.

---

N.B. the article mentions the 1926 Soviet census. Readers interested in the demographic history of Abkhazia should consult the chapter 'Demography' by Daniel Müller in the book 'The Abkhazians: a Handbook' (Curzon Press, 1999, edited by George Hewitt) in order properly to understand the figures available for the population of Abkhazia since 1886.

See also: Demographic change in Abkhazia 1897–1989.

Source: Conciliation Resources