Estonians in Abkhazia by Aivar Jürgenson

Estonians in Abkhazia (1940)

Aivar Jürgenson | Special to AbkhazWorld

Estonia as a country of emigration

After the end of the Caucasian war (1864) and deportation of much of the Abkhazian population, Abkhazia became an important destination country of colonization in the Tsarist state. Thus the Greeks, Russians, Moldavians, Armenians, Bulgarians, Georgians/Megrels, Germans and also Estonians arrived in Abkhazia.

Before migration began, Estonians had been relatively settled peasants for centuries. Up to the middle of the nineteenth century, the Estonian diaspora comprised only three to four percent of the entire population and, of the few settlers who had, most lived in Russia. One of the reasons for the small number of Estonians living outside of their ethnic habitat was serfdom. As a result of the foreign conquest that occurred in the thirteenth century, the Estonian population had fallen into serfdom and the land—which was the main means of production and source of work in an agrarian society—was in the hands of the upper class, which was of foreign (primarily German) ethnic origin. After the Great Northern War (1700-1721), Estonia fell under the Russian tsarist state. While serfdom had been abolished in Estonia between 1816 and 1819 and the peasants no longer lived in servitude in the narrowest sense, the land remained the property of the manor owners, and peasants were still forced to work at the manor owners´ fields in order to survive. In addition, their movement was restricted to the boundaries of the province. Estonian peasants were not permitted to become landowners until the middle of the nineteenth century, when the new peasantry laws began to allow property ownership for the first time. At the same time, the new peasantry laws also provided the peasants with the opportunity to emigrate.

Emigration from Estonia occurred in three waves. The first of them was to Crimea and Samara, starting in the 1850s and continuing over the subsequent decades. The second wave, in which people moved to the Caucasus, to the central of Russia and to Siberia, occurred in the 1880s, and the third, to the Northwest Russia and Siberia, lasted from 1907 to the 1910s.

The main pull factor favouring migration was provided by the settlement policy of the Russian state in the second half of the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. The state’s territory had expanded by almost twenty percent in the first half of the nineteenth century.

There were several motivating factors behind the colonisation policy. On the one hand, the rulers had the purely colonialist aspiration to secure its power in its new territories and, on the other, resettlement acted as a valve to release the population pressure in the densely settled areas of the state’s other regions. Broad-based migration from European Russia could start only after the enactment of a law in 1861 that freed the peasants of the country from serfdom.

However, the peasants of the Estonian and Livonian provinces, who by this time had been free from serfdom for several decades, had the opportunity to migrate even earlier.

The beginning of the Estonian settlements in Abkhazia

In the 1880s, a number of Estonian villages were founded in Abkhazia, which at that time was divided between two districts: Upper and Lower Linda and Estonia in Sukhum district and Salme and Sulevi in Sochi district. Estonians also lived in the cities Sukhum and Gagra. By the end of 1886, 846 Estonians lived in the Sukhum and Black Sea districts. (1926 lived in the territory of Abkhazia 1633 Estonians, in 1939 – 2282). Traditionally, in Estonia the peasants had grown rye, barley, wheat and oats. Climatic conditions and the market situation in the Caucasus led to changes in livelihoods. Traditional crops were replaced with maize at the end of the 19th century. When the price of maize on the world market fell at the beginning of the 20th century, the focus was now on fruit growing. The main products in Estonian settlements of the Sukhum district were peaches, in Sochi district black plums. Later, tobacco was also grown.

Estonians in Abkhazia are preparing for the Estonian Song Festival (1947)

Cultural life was active in Estonian villages. Choirs and brass bands existed in the settlements, even an Estonian song festival was organized in 1914 in Sukhum, which was also visited by performers from another Estonian settlements and from motherland Estonia. Most Estonians in Abkhazia were members of the Lutheran church. Cultural ties with Estonia were active: newspapers from Estonia were ordered to the Estonian settlements, from Estonia came school teachers. In addition to teaching, the task of the school teachers was also to promote the cultural life in Estonian settlements. One of the active school teachers, who organised cultural life in Estonian settlers’ society, strengthening their ties with the motherland Estonia and organising a correspondents’ network to collect folklore and write down memories in their villages, but who also played a role in Abkhazian political life, was August Martin, a school teacher in the Estonian settlement Upper Linda.

+ 1930. aastad Kaukaasias “Edasi” kolhoosis põllumehe silme läbi ja ajalehe “Edasi” veergudel I - Marika Mikkor

+ Selected works of Marika Mikkor

August Martin (1893-1982) in Abkhazia

Martin arrived in Abkhazia in 1915, after he had been prohibited from work as a school teacher in Estonia for political reasons. As an active person, Martin organised the cultural and economic life of the Estonians in Upper Linda village and Sukhum. From 1916, he was a member of the board of the Estonian Economic Society of Sukhum, as well as the chairman of the Education Society of Upper Linda village. In 1917 he was elected the chairman of the council of the Estonian settlements in South Caucasus.

August Martin

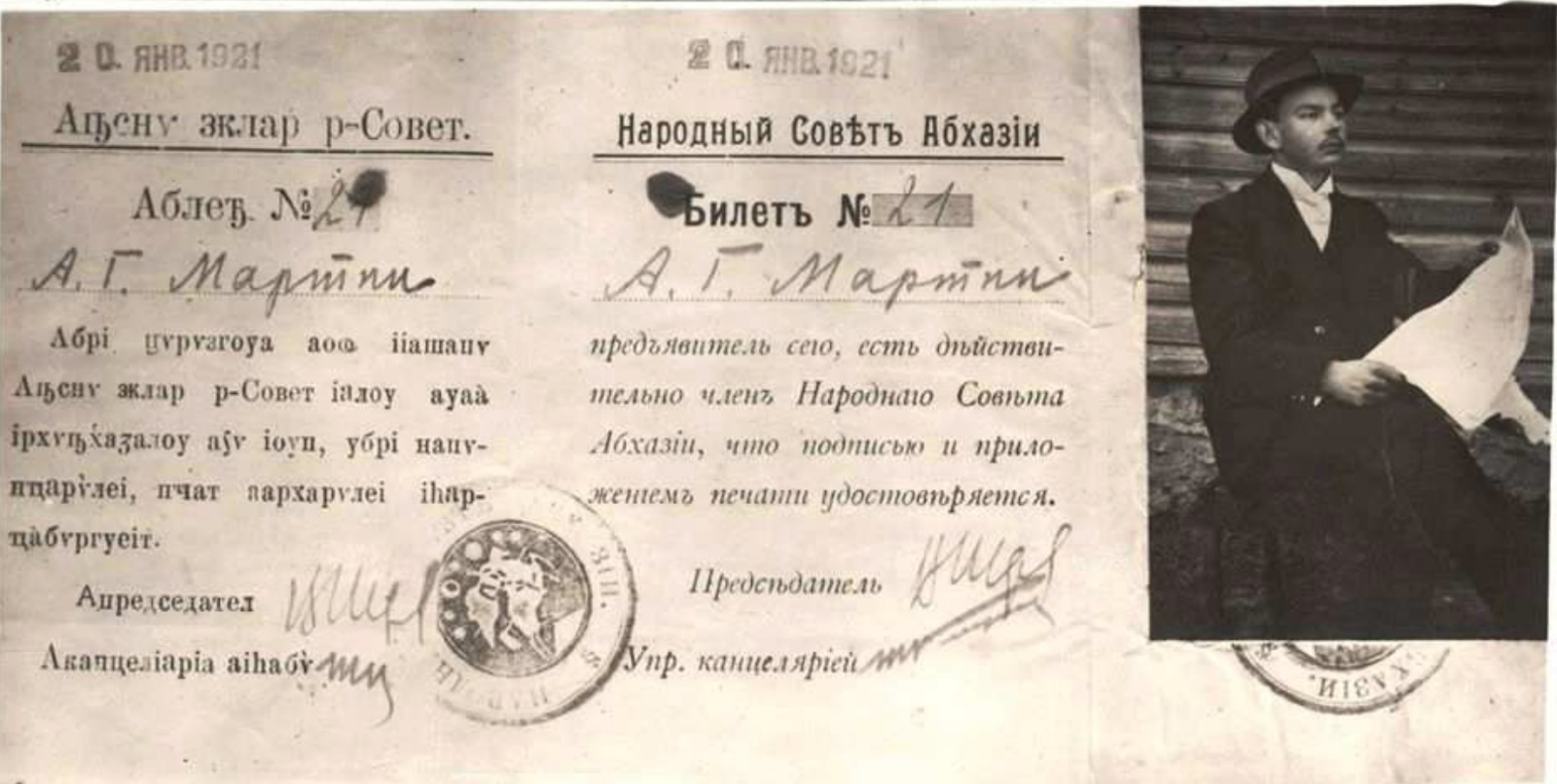

The time of revolutions and civil war of Russia had a great significance in the bordering countries. Estonia won his independence in 1918, in Abkhazia, Abkhazia´s national independence, which had been lost in 1864, was restored the same year. Georgian Mensheviks annected the territory of Abkhazia in 1918. Elections for the third composition of the Abkhazian People´s Council were held in early 1919. The Estonian settlers who lived in three villages in the Sukhum district nominated their own list of candidates. August Martin succeeded in being elected to Abkhazian People´s Council with the support of Estonians, but also of others. He formed a separate one-member colonist´s fraction that cooperated with proponents of Abkhazian independence in opposition in the Abkhazian People´s Council (renamed the People´s Council of Abkhazia in the spring of 1919). Because of his pro-Abkhazian thoughts and activities in Abkhazia, which since the summer of 1918 had been occupied by Georgian militants, August Martin found like-minded people among Abkhaz patriots, but fierce opponents among Georgian Mensheviks, who formed the parliamentary majority. The Georgian Minister of Internal Affairs Noi Ramishvili applied pressure to Martin to revise his political views. But he had no luck. August Martin continued to support the aspiration of the Abkhazian people for sovereignity.

Translation: January 20, 1921 People's Council of Abkhazia A.G. Martin The holder really is a member of the People's Council of Abkhazia, which is authenticated by signature and stamp.

The People´s Council of Abkhazia was dissolved in March of 1921 when Bolshevik forces invaded Abkhazia and Soviet power was declared. August Martin left Abkhazia for Estonia in May of 1921 and continued to work as a school teacher. During the 1920-30s, relations between the Soviet Union and most of its border states were poor for ideological reasons. Because of the closure of the borders contacts were almost broken off. August Martin visited Abkhazia next in 1958. Only now he became aware of the fact that some of his good colleagues in the People´s Council of Abkhazia were killed in the years of Great Terror of the 1930s.

+ August Martin: An Estonian as a Member of Abkhazia’s Parliament, by Aivar Jürgenson

+ Август Мартин и эстонские материалы о событиях в. Абхазии (1917–1921 гг.) - Станислав Лакоба

+ How the NKVD Searched for Estonian Spies during the Great Terror in 1937—1938

Estonians in Abkhazia in years of Great Terror (1937-1938)

The Soviet authorities carried out mass repressions in several stages in the 1930s. The most extensive of these was the declaration of the more enterprising and prosperous sector of the rural population as kulaks in the course of the collectivation of agriculture in 1929, after wich up to 2 million people were repressed. The mass operations of 1937-1938 were the culmination of the Stalinist repressions directed against their own land and people. In these operations, the NKVD arrested approximately 1,575,000 individuals, of which 681,692 are known to have been shot.

The overwhelming majority of repressions was carried out in the course of so-called mass operations, which were processed outside of the attention of the public. Mass operations primarily mean „national operations“ and „kulak operations“. In the course of kulak operations, where the social origin of the people was the decisive factor, 55 Estonians by the NKVD of Georgian SSR were arrested and convicted, of them 37 persons were sentenced to death and 18 persons were sent to prison. During the national operations 16 Estonians were convicted, 11 of them were shot down and 5 were sent to prison. In addition to the troika decisions, there were so-called Stalinist lists, which dealt with representatives of the Tsarist era as well as of the Soviet elite. From May 1937 to November 1938, six Estonians were placed on the Stalinist lists in the Georgian SSR, all of whom were sentenced to death. Estonians were accused of actions against the collectivization of agriculture, anti-Soviet propaganda and ties with their motherland, Estonia. The NKVD fabricated Estonians in Abkhazia guilty of setting up counter-revolutionary organizations in their villages. According to the NKVD prosecutions, in the war that would supposedly begin in the near future, the members of the Estonian counter-revolutionary organizations were ready to organize an uprising in Estonian settlements and support the intervention of Western armies in Abkhazia by diversion acts and by mediating information for Western military forces.

The people targeted in national operations were prevailingly charged with spying for the countries of their origin. The „uncovering“ of a German-Estonian espionage network was staged in Abkhazia in the summer of 1937. 63 persons were arrested in the course of the NKVD „uncovering operation“. The arrested persons were charged with long-term espionage for Germany and/or Estonia – local Germans spying chiefly for Germany and Estonians for Estonia, but some individuals were made spies of both countries. As shown, most of the convicted Estonians were executed. Some Estonians were sentenced to prison; however, in many cases imprisonment could have been the same as the death penalty because only a few Estonians returned from prison camps to their home villages. The elite of Estonians in Abkhazia was destroyed in the course of the kulak and nationalities operations that were carried out in parallel. These were individuals who had already promoted local Estonian economic and cultural activity in the tsarist era and maintained connections with their Estonian motherland.

At the end of World War II in 1944, the Soviet Union annexed Estonia. Like in the Tsarist times, Estonia and its eastern diaspora settlements were once again part of the same state. In the decades that followed, many Estonians have repatriated from Abkhazia to Estonia. Contacts between Estonia and Abkhazia were close – several Estonian institutions and enterprises had holiday centers in Abkhazia, some even in Estonian villages there. Many Abkhazian Estonians lived alternately in Abkhazia and Estonia, many who lived in Abkhazia, found a market for their agricultural products and flowers in Estonia.

Georgian-Abkhaz war (1992-93) and the Estonians in Abkhazia

As the interviews I have conducted with Estonians in Abkhazia show, the bloody war affected the attitude of Estonians toward Georgia, which is predominantly negative. In the war Georgia was perceived as an aggressive and dangerous neighbour, and this attitude has not changed today. The keyword of war memories is fear, something that was constantly felt during the shootings, rocket attacks and bombings during the war. The Georgians are accused of aggression and the Abkhazians and other residents of Abkhazia, who were defending their homeland, are justified in interviews. The freedom-fighting narrative, which is clearly anti-Georgian, is mirrored in the stories of those who survived the war. Besides the historical image being instilled in Abkhazia, which is also being promoted by the media, a psychological factor is also responsible for the relatively similar tone of the memories: when talking about the past, one seeks to reconcile with it. One’s personal choices must be situated in a logical place in one’s biography. A quarter of a century ago, when people made their choices, they did not know how the war would end. During the war, the Estonians were provided with the choice between staying in Abkhazia or leaving. Many Estonian men fought Georgian invaders in a battalion of local Armenians.

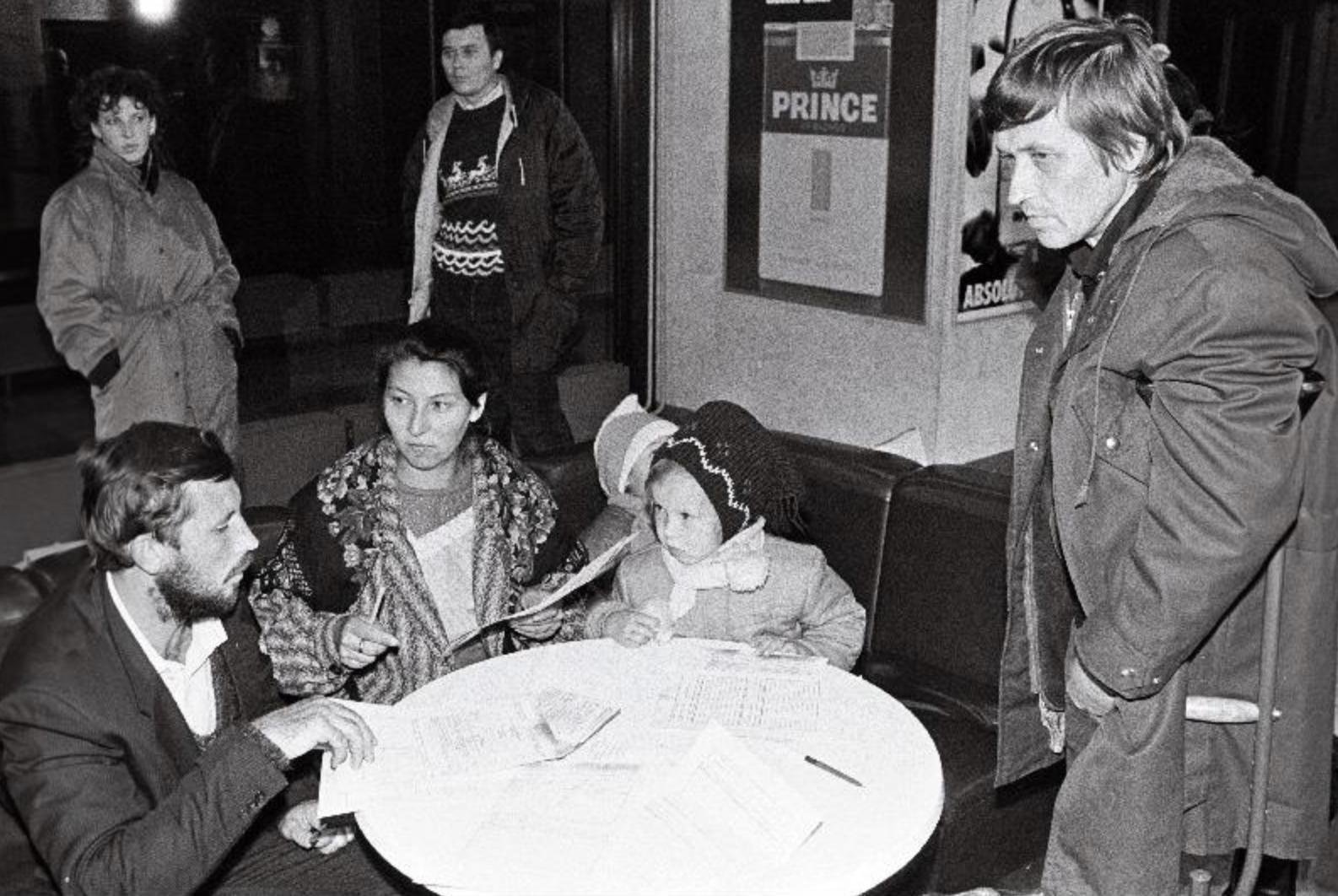

As is usual in the case of armed conflicts, the war that broke out between Georgia and Abkhazia in the autumn of 1992 also raised the theme of refugees. Just as Israel evacuated Jews from Abkhazia to Israel and Greece evacuated ethnic Greeks to Greece, the Republic of Estonia decided to evacuate Estonians from the war zones in Abkhazia. It was the first humanitarian mission of the once again independent (1991) Republic of Estonia. 170 Estonians and members of their families, most of them from Sukhum district of Abkhazia, were brought to Estonia using three flights (23-24 October, 29-31 October and 21-23 November). The overall coordination of the rescue operation was delegated to the Estonian Migration Board, while at the samet time the Rescue Board team did much of the actual work. Both of these agencies had just been established and tried to prove themselves in the best possible light in the course of the operation. Forty-two of the 170 evacuees that arrived in Estonia were children and 20 were of retirement age, the reminder were of working age. It means that primarily younger people leaved, while older people mostly stayed at home.

Thus the need unexpectedly arose to quickly work out a repatriaton policy of Estonia. The operation attracted a great deal of attention in Estonia´s media. Repatriation made it necessary to establish accommodation conditions for the evacuated persons, and required the existence of an integration policy – the events of that time provided material for discussion from this aspect as well.

The Evacuation of Estonians from Abkhazia in 1992

The total number of people arriving in Estonia from that crisis area was not limited to those who were evacuated in 1992. From the beginning of the crisis in 1992 to 2001 a total number of the refugees from Abkhazia was 570 people, including family members of Estonians. It means that many of these persons traveled to Estonia independently of the Estonian state evacuation operation. Interviews conducted a few years later with Estonians who relocated from Abkhazia to Estonia show the fact that for them, the concept of home is associated more with their home village in Abkhazia. Many of them experienced difficulties in adaptation and integration in Estonia. Some of them returned later to Abkhazia to their home villages.

Today, the majority of Estonians in Abkhazia live in two villages Psou [Псоу, estonian name Salme] and Pshouhua [Пшоухуа, estonian name Sulevi] – 2015 officially 114 inhabitants. The former Estonian villages Upper and Lower Linda have disappeared by now. The final blow to the villages was the war 1992-1993. Estonians are living also in the following cities: Sukhum, Gagra and Agudzera. Few Estonians are living in the village Dopuket [Допукыт, estonian name Estonia].

Conclusion

The Estonian villages in Abkhazia were established more than 130 years ago. While in the first decades the diaspora was developed by a cultural field shared with Estonia proper by subscribing to Estonian newspapers, importing school teachers and having regular correspondence with relatives back home, then these ties were severed when bolsheviks seized power in Abkhazia and Estonia broke free of the empire to become an independent state. For the two decades that followed these events, communication between the Abkhazian Estonian diaspora and Estonia was not as productive as it had been. Ethnic minorities in Soviet Union were stripped of the freedom for cultural self-expression, which often led to physical extermination of cultural and economic leaders. After the Second World War many waves of repatriaton from Abkhazia took place to Estonia, the last of which was during and after the Georgian-Abkhaz war. Long-term separation from the cultural field of motherland has developed different mentalities in diaspora and the motherland. Also the different climate conditions have complicated the adaptation after repatriaton. Although many Estonians from Abkhazia are well adapted in Estonia, this is not the case with everyone. Some have returned to Abkhazia, where they feel at home.

Aivar Jürgenson

Senior Research Fellow in School of Humanities, Tallinn University, Estonia.