Establishment of the Estonia village on the bank of the Kodor River at the end of the Tsarist era, by Marika Mikkor

On the banks of the Kodor River near the settlement of Estonia. Photo: © Marika Mikkor, 1997.

This article was first published on March 1, 2023 in Russian in the Athens-based Greek diaspora newspaper "Aфинский Kурьер" No. 4 (1059) in the section "ГРЕЧЕСКИЙ СУХУМСКИЙ ВЕСТНИК" (No. 201). Марика Миккор. "Основание села Эстонка на берегу реки Кодор в конце царской эпохи."

Marika Mikkor is a historian who graduated from the University of Tartu and has worked at the Estonian National Museum and Estonian Agricultural Museum as researcher and senior researcher. She has expertise in topics such as Estonian customs, Izhorian and Mordovian family customs, Nazi skinheads in Estonia, identity of Caucasian Estonians, and the home birth movement in Estonia. Mikkor has conducted extensive fieldwork and has been actively involved in raising awareness about the challenges faced by Estonians in the Caucasus.

I dedicate this article to Elviina Jakobson, at whose house I stayed several times in the village of Estonia in the 1980s.

During the colonisation of the Black Sea coast of the Caucasus, Mingrelians and other Georgian tribes from neighbouring counties settled in the region, as well as Greeks, Armenians, and other refugees from the Ottoman Empire. Georgian officials wanted to relocate compatriots suffering from a lack of land plots to the region, while some bureaucrats preferred settlers of other nationalities. In 1864, the migration of landless peasants from Mingrelia began. In 1866-1867, the first small settlements of Orthodox Bulgarians and Greeks were founded in Abkhazia. Soon, Estonians, Germans, and Latvians, mainly Lutheran economic migrants, arrived.

Estonian settlements were established around Sukhum and in the area between Gagra and Adler. One of these settlements, the village of Estonia (also known as Estonka), was situated on the right bank of the Kodor River at the foot of the Greater Caucasus Mountains, twenty kilometres from Sukhum in the direction of Tiflis. This area was part of the Guma District within the Sukhum Military District of the Kutaisi Governorate.

The settlement of Estonia was founded in 1882 by Estonians from Samara, and later, migrants from Crimea and homeland Estonia joined them.

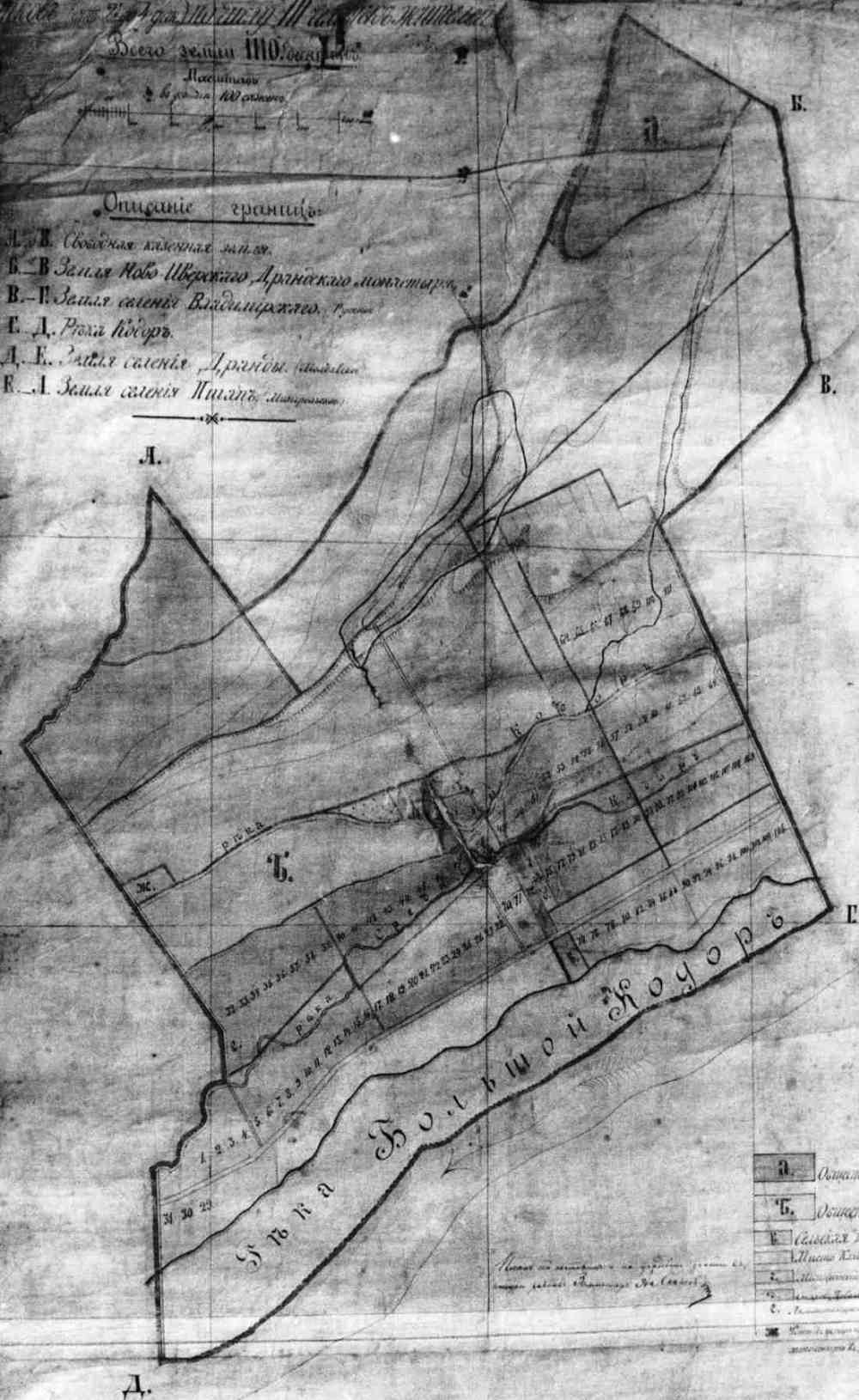

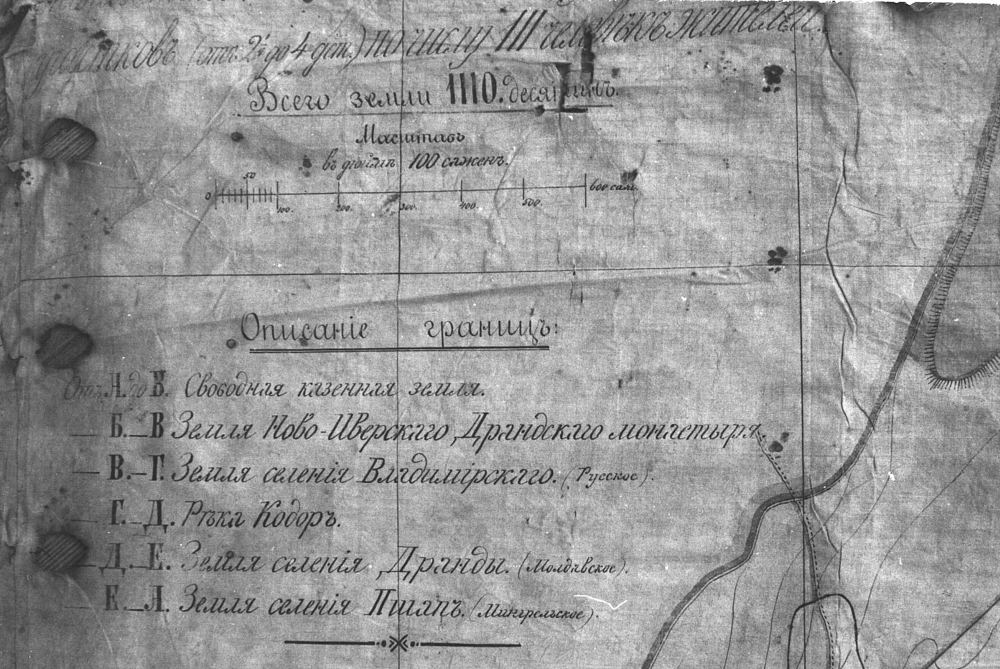

Map of the village of Estonia from the mid-1880s. Photo: Üllas Erlich, 1996.

Jakob Pint wrote about the migration of his ancestors from homeland Estonia to Samara around 1864. His grandfather, Adam Pint, from Tartu County, went to St. Petersburg with other envoys to obtain permission for resettlement. Upon returning home, the peasants faced corporal punishment for such actions. Thirty years later, as wealthy men in the Caucasus, the former Samara Estonians bitterly recalled how they left homeland Estonia: "We had to escape at midnight, but the unfortunate escorts were punished and received 30 lashes." At that time, Estonian peasants were ruled by German landlords.

After twenty years of living in Samara, Estonians achieved prosperity thanks to favourable conditions—they no longer had to serve German landlords. However, they grew tired of blizzards in the open spaces and long trips to the city. Moreover, the region suffered from crop failures for several years. The main reason for their migration, though, was to obtain new land that was not taxed.

They began to move to Siberia, Bashkiria, the Ufa province, and the Caucasus. The Samara Estonians learned about the resettlement to the Caucasus from the newspaper articles "Kaukaasia kirjad" (Caucasian Letters) by Joosep Robert Rezold, a gymnasium teacher living in Tiflis. Representatives of other nations also called for the colonisation of Abkhazia. Georgian public figure and educator Jakob Gogebashvili published an article titled "Who should be settled in Abkhazia?" in the newspaper "Tiflis Vestnik [Тифлисский вестник]" in 1877. In his opinion, the Mingrelians living nearby were the most suitable settlers for Abkhazia.

Estonian pioneers initially chose a plot of land near Sukhum, in a place called Abzhakva, but this did not satisfy the 27 families who arrived from Samara in May 1882. They needed flat land, and the new location chosen was the bank of the Kodor River. Only 10 out of the 27 families became the founders of the village of Estonia, while the rest returned to Samara disappointed.

The settlers became tenants of state lands, initially granted 10 years of tax exemption, a period that was later extended for another 10 years. The nearest Abkhazian village was located across the Kodor River. Since 1877, Abkhazians were considered a "guilty population" in the Russian Empire and were not allowed to live near Sukhum. They were suppressed by the tsarist government after the anti-colonial uprisings of 1866 and 1877. On the right bank of the Kodor, the tsarist government established a buffer zone of loyal and grateful settlers from various nationalities and Christian denominations.

Estonian settlers camped on the bank of the Kodor River until a colonial government official rode up and pointed out the village's borders with the handle of his whip. The settlement bordered the Moldovan village of Dranda, the Mingrelian village of Pshap, and the Russian-Bulgarian village of Vladimirovka. The Estonians named their village Estonia.

Then they began to measure out plots for families. Each family, on their allocated plot, cleared part of the forest so they could place boxes and bags containing the belongings they had brought with them. They brought tools, clothes, food, etc., from Samara, and many necessary items were purchased in Sukhum. The village was built in a forest where, in addition to ferns, there were alder, walnut, and oak trees, beech, and others, most of which were burned down. Only walnut trees were preserved by order of the authorities. In some places, apple, pear, and fig trees, grapevines, and so on, left by the Abkhazians, were growing.

During the clearing of land plots, trees and other vegetation were burned, meaning the slash-and-burn agriculture method was used. To move around in the forest, it was necessary to clear a path with a bush knife. In the first year of settlement, fires burned continuously throughout the year, enriching the arable land with ash. The forest could be burned and destroyed as much as desired, but selling it was not yet allowed, although it could have fetched a good price. In areas with fewer walnut trees, other fruit trees were left in the field: figs, apples, etc., left by the Abkhazians, both for food and shelter.

Later, permission was obtained to sell part of the walnut trees. Walnut timber was exported abroad, where it was made into plywood, and then part of it was bought back to Russia in the form of plywood for a lot of money. With the first such deal, each owner received money. Since walnut trees were not present on all plots to the same extent, the second time the money from their sale went to benefit the community.

Walnut trees were a reminder of the indigenous inhabitants; they grew exclusively in former settlements. A hundred years later, in the village of Estonia, I was told that some farm wives add walnuts to their food daily. The fact that they are so valuable is evidenced by the old jokingly saying by Elviina Jakobson: "Even if you fry old leather shoes with walnuts, it will be delicious." Today, walnuts are a globally known superfood. However, Abkhazians have been known since older times for their healthy food, lifestyle, and longevity.

In all the Caucasian colonies, settlers used the fruits of the fruit-bearing trees left by the indigenous people for food and sale. In the works of the Caucasian Department of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, information from the Black Sea Province describes how settlers of different origins entered into conflicts with each other when collecting Circassian fruits and nuts.

In the village of Estonia, temporary huts were built for living, and three of the wealthiest owners bought ready-made houses in a neighbouring village, which they transported to their plots, installed stoves, and furnished them for living. In winter, they also let other compatriots into their homes. The first settlers stuck together and helped each other. Initially, it was a small community of old acquaintances.

Soon after arriving at their new residence, people began to get sick with malaria. A paramedic sent to the village to treat malaria distributed quinine for free. Nevertheless, many people died from malaria. The Kodor Valley was a more dangerous place in terms of malaria spread than the Linda area. However, for the Linda settlers who arrived from homeland Estonia in 1884, it was no easier to survive, as they were less financially secure and less experienced as colonists.

The first planting in the settlement of Estonia was done in the spring of 1883. From the very beginning, the main focus in Estonka was on growing corn. Maize was a new crop for Estonians, but they were informed that its cultivation was the most affordable in the region. (Among the Estonian colonies, only those in Estonka were smart enough to immediately trust the information they received. Estonians from Samara were more flexible and experienced colonists.) The Estonians referred to this new grain using the Russian term – "kukurus." Potatoes were planted, vegetables (beans, pumpkin, and carrots) were sown, as well as a small amount of wheat, barley, and rye.

The new land could not be ploughed with a plough due to the large tree roots. Hoes or field axes were used to make small holes between the roots where corn was sown. Since the cleared plot of land was initially small, the crops were sown around the hut or house.

In the first years, corn yielded an excellent harvest. It was said that if a person filled their pocket with corn seeds for planting using a hoe, and they had enough cleared land, they would have bread for a whole year.

By the fall of 1883, the first settlers had their homes ready. Money from the sale of the first corn had already been used to buy window glass and stove stones. Houses were built on stilts slightly above the ground due to humidity. Construction also depended on the personal abilities and skills of each person. Outbuildings, such as barns and sheds, were also completed.

This type of house was the first in the village of Estonia (the Konno family house in Lower Linda). Presumably a photo by August Kaevats, 1925.

Although the former Abkhazian settlement had become overgrown with forest before the arrival of the Estonians, while working on the land, Estonians found not only fruit trees but also other signs of the area's previous owners. They discovered wine vessels in the ground. Jakob Pint recalled, "According to Abkhazian custom, a pot of wine is buried in the ground for each child on their birthday, which must remain there until either their wedding day or the day of their death; wine is not taken for use at any other time except the designated special day. Therefore, Estonians also stumbled upon wine pots left behind on abandoned Abkhazian sites after many years. It was said that the wine had thickened and was consumed mixed with water, which was very alcoholic and caused drunkards drunkenness after just a small glass. Wine must always be present on the Abkhazians' dining table, and they drink it in moderation, not to get drunk. They only get drunk at certain festive events or weddings. Drinking customs were, of course, not strictly observed among Estonians, and in most cases, when consuming Estonian wine, Estonians did not adhere to any limits or moderation."

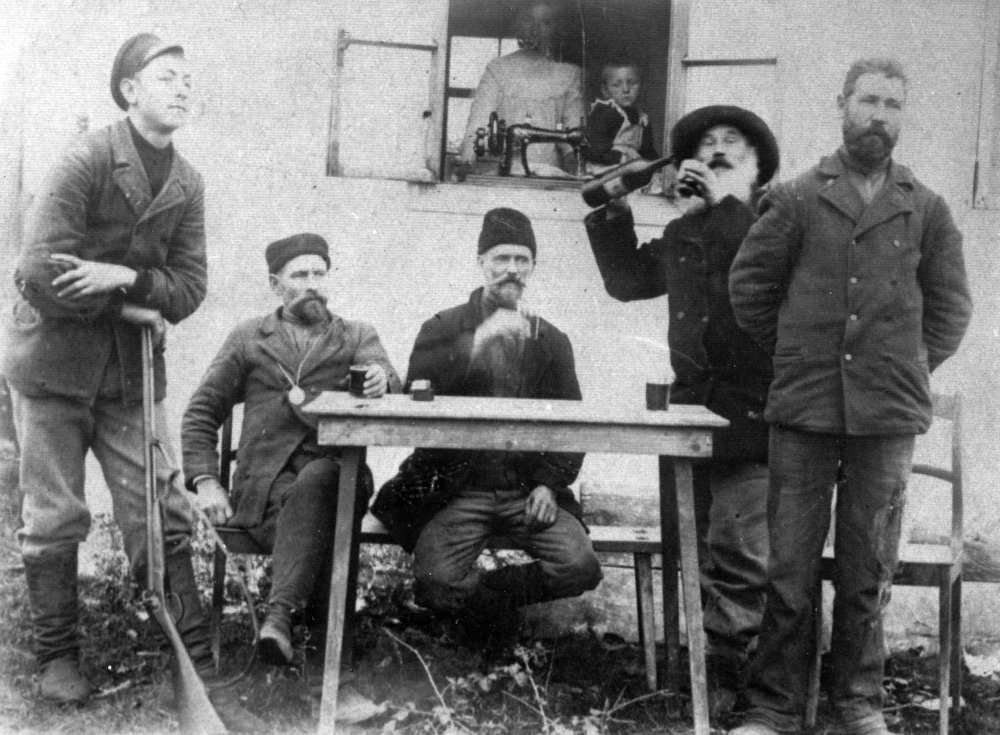

Company at Jaan Bärjet's house. Village of Estonia.

The colonists did not know exactly who lived on this land before and what their fate was, whether they were killed or fled to the Ottoman Empire. In the mid-1990s, after the Georgian-Abkhazian war, Estonka began to be called Dopuakyte, meaning the original 19th-century name was restored.

Colonial officials allocated land from former indigenous inhabitants to migrants, but sometimes they themselves did not have accurate information about where exactly the borders of one settlement or another passed. However, when impassable forests were declared suitable for colonisation, it was the traces of previous settlements that played a decisive role, such as fruit trees and piles of stones accumulated during land clearing near former fields.

Estonian colonists were attacked by bears, wild boars, and cattle thieves. Wild boars came to the fields both at night and during the day in entire herds, eating everything. Bears appeared one after another at night. To repel bears, noisy tin dishes were used. To protect against wild animals, the settlers were issued Crimean military rifles, and they built covered platforms in the trees where they served night duty, clapping, jingling, and shooting their rifles. Bears and wild boars were shot right on the streets of the village, thus providing valuable additional food. Residents of Lower Linda (Alam-Linda) recalled that in the first years of the village's existence, they ate the meat of wild animals, including bear meat, all year round, salting, smoking, and drying it in the sun.

Bear hunting in Lower Linda, 1910s. Photo by August Kaevats.

In November 1883, the settlement of Estonia was visited by Ferdinand Hörschelmann, the pastor of the German Lutheran community in Tiflis. He held a religious service and brought people to communion in Gustav Suits' house. Hörschelmann was German but spoke Estonian fluently, and people treated him well. During his next visit, the pastor ensured that Estonians held church services for Lutheran rural residents every Sunday and engaged in teaching children. The most knowledgeable and competent settlers conducted worship services, funerals, and baptisms.

Most Estonian settlers were Lutherans, and power in the settlements was in their hands. They also wrote most of the newspaper reports and memoirs, and the village administration was headed by Lutherans. Thus, it often created the impression that all Estonians were Lutherans. However, there were also Orthodox Estonians.

+ Kaukaasia eestlaste usuelust ja ristimistavadest (On religious life and baptism rites of Caucasian Estonians), by Marika Mikkor

+ Selected works of Marika Mikkor

+ Funeral customs of Caucasian Estonians, by Marika Mikkor

+ 1930. aastad Kaukaasias “Edasi” kolhoosis põllumehe silme läbi ja ajalehe “Edasi” veergudel I - Marika Mikkor

Orthodox Estonians also performed baptisms and funeral rites themselves. In 1901, the Estonian newspaper "Uus Aeg" reported: "There have been more than two hundred Estonian Orthodox living in the vicinity of Sukhum for 17 years, but they have no connection to the church other than marriage. About ten years ago, they went to the local bishop to ask for a priest who understands the Estonian language to be appointed for them. The bishop ordered them to submit a written request, which they did, but it was ignored. Their children attend a Lutheran school where they learn to read and write, but they don't know religious teachings. Although there are plenty of churches in the area, they have to stay away from them due to the language barrier. In the city of Sukhum, there are several priests, and it would be preferable to have a priest appointed who understands the Estonian language, as Estonians live on both sides of the city."

In the Caucasus, some Orthodox Estonians even converted to Lutheranism. And this occurred despite the fact that Orthodox Christians lived around them. In tsarist times, Estonian colonies were somewhat closed Lutheran cultural enclaves.

In the spring of 1884, a village administration was elected: a village elder, three judges, and a clerk. The first village elder was Ants Maitus, a gardener from Crimea. At the end of summer, Maitus died and was replaced by Peeter Pint from Samara. That same year, on Peeter Pint's plot, the state built a large wooden barrack house with six rooms, where new migrants found their initial shelter. This barn became the first Lutheran prayer house the following year when a prayer hall was built at the other end of the barn.

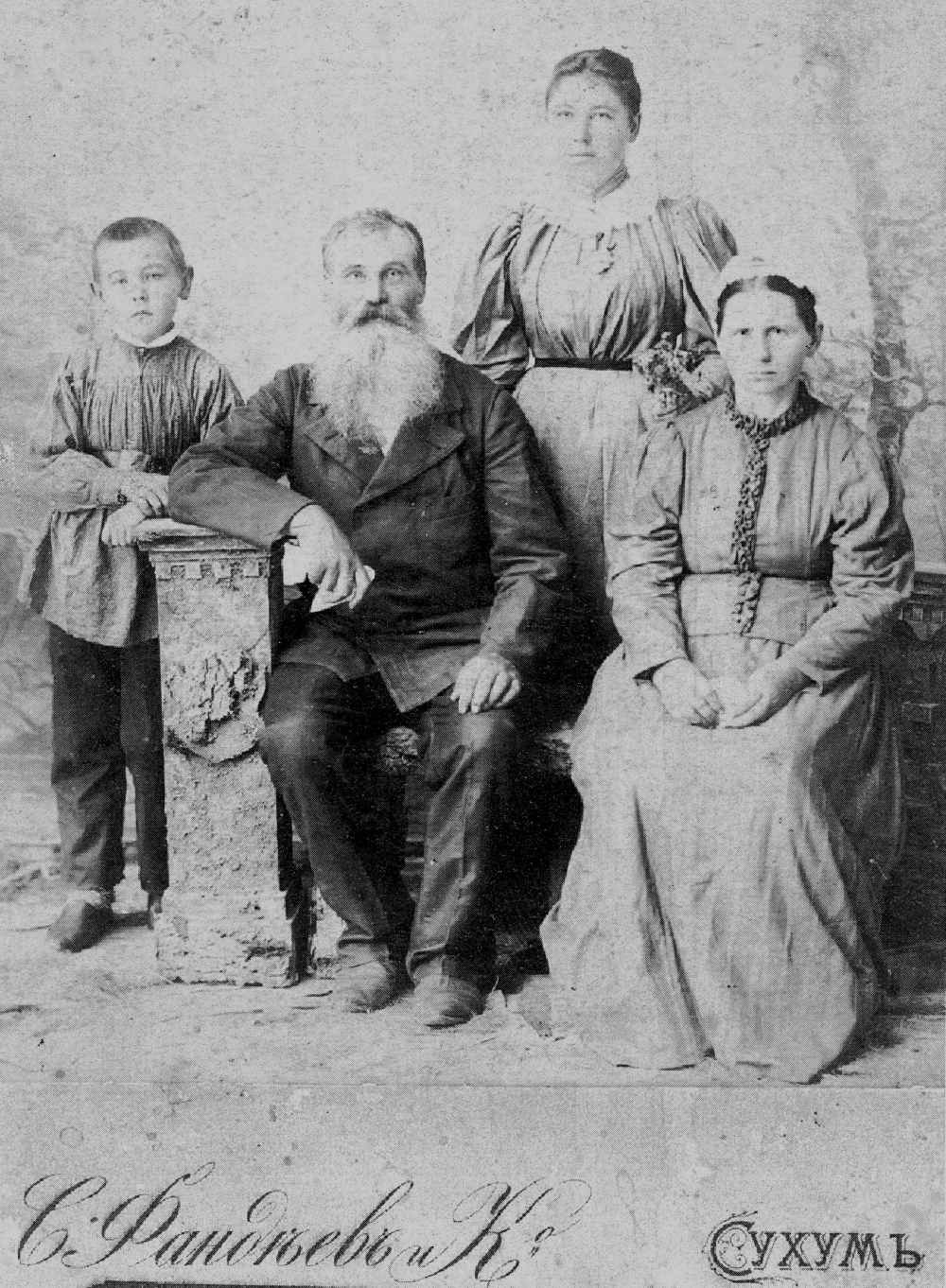

One of the first village elders, Peeter Pint, with his wife Mari and children Jakob and Liine. Photo by S.S. Fandeiev, 1899.

In 1884, new Estonian settlers began to massively settle around Sukhum. At that time, the Estonian colony of Linda was also founded in the same place where Abzhakva was located. Among the new colonists from Crimea, large families Auner, Truman, Kala, and Liiv arrived in the settlement of Estonia. Less affluent colonists from homeland Estonia and young people who wanted to avoid military service also arrived. In 1884, there were more than 100 families in the village of Estonka. More and more people arrived, but many also left. According to the census throughout the Sukhum district (Abkhazia) in 1884, there were more than 400 Estonian families. 113 of them lived in the settlement of Estonka, while the rest were located in the new Estonian colony of Linda, founded in the same year, and in Salme, which appeared near Adler and Gagra.

The population of the colony of Estonia was initially diverse, ranging from wealthy families from Samara (one of which brought a personal library of a thousand books) to the family of Andres Puss from homeland Estonia, who arrived on foot with his wife and four children across Russia, carrying some belongings and small children in a handcart. The reason for resettlement to the Black Sea was the fact that everyone was attracted by duty-free rental land and the desire to escape from the rule of the German landlords. They were also drawn to the exemption from military service, along with the offered loans and other forms of promised support. The Samara settlers liked the forests and water, which they lacked in the plains of Samara. Above all, another resettlement was a favourable business project, because prosperity had already been achieved in Samara. They sub-leased or resold their right to use Samara lands, and became rent-free land users in Abkhazia again.

In 1884, a surveyor clarified the village boundaries of Estonia. A total of 1,110 dessiatins [Russian unit of land area equal to 2.7 acres. -ed.] of land was allocated for the entire settlement, for 110 families and a school. Each family or adult male who wanted to live independently was given 10 dessiatins. The land was divided into yard plots and arable land, as well as forests and pastures. Each yard had 2 dessiatins. Unlike other Estonian villages in Abkhazia, in Estonka, the yards of the homesteads were densely and row-wise located. The forest was in common use.

In 1884, on the first day of Christmas, a choir created by Kristjan Suits performed two spiritual four-voiced choral songs, "Hosanna" and "Praise the Lord, all you Gentiles!," during the worship service. This marked the beginning of choral singing in the village of Estonia.

In 1885, Estonian newspapers (from the homeland) warned that no one could move to the Sukhum district anymore because free state lands were exhausted. However, many of the families in the village of Estonia soon died out or left. In 1888, it was claimed that there were about 60 heads of households in the village of Estonia. Some settlers who had 2-3 plots sold others the right to use the excess land.

Authorities visiting the colonies were always pleased with the Estonians. They were treated to performances by the choir and later by the orchestra. In 1883, the settlers received a loan from the state of 90 rubles per family. In 1884, in addition to flour, semolina, and grain, the state allocated 32 cows from the Kuban district to the needy colonists. (In the memoirs of the villagers, it was claimed that the flour had "worms an inch long.")

Choir. In the first row on the right is Jakob Mihkelson. Village of Estonia. Early 1890s.

Animals were given to poor families who did not yet have a cow. The price of each animal was set at 30 rubles, which was to be repaid within a few years.

In 1886, Estonians were provided with loans of horses, the price of which was 35 rubles per animal. Many of them perished. Most of the debts were later annulled by "imperial manifestos." The old-timers of Lower Linda recalled that later, with the birth of the emperor's heir, the debts were written off.

Immediately after the establishment of the village, the Mingrelians, who lived nearby, and the Abkhazians, who lived across the river, began stealing Estonians' horses, engaging in horse theft. The authorities helped Estonians catch the thieves. From the villages where the trails of the missing horses led, they demanded 2-3 times the price, but the victims did not receive the money... In reality, in most cases, the thieves were not caught.

Communicating with representatives of other nationalities, Estonians initially interacted mainly with official persons of Russian and Georgian nationality. The native inhabitants of the region, the Abkhazians, were hostile to the colonists.

On the other hand, the Abkhazians were more negative towards the representatives of the tsarist government than towards the settlers. A man from homeland Estonia who visited the Sukhum district in 1887 wrote about the attitude of the "Circassians": when he asked them in Russian for directions to the Estonian colony, they did not give directions; when he asked in Estonian, they pointed out the correct way. Estonians were sympathetic to the Abkhazians. The fate of the natives was treated with compassion.

Estonians had friendlier contacts with other colonists, such as Bulgarians and Moldovans living close to the settlement of Estonia. Communication was complicated by the fact that at the time, the Turkish language was the language of communication between the peoples who had lived in the Ottoman Empire earlier. In the 1880s, Turkish was indeed the dominant language of interethnic communication among the common people in Abkhazia; however, Estonians did not know this language. The language barrier was exacerbated by religious differences, so initially, communication with Orthodox neighbours from other nations in the villages was minimal.

The first school-church in the settlement of Estonia, built in 1887. Photo from the 1910s.

In 1886-1887, the Fund for Assistance to Evangelical Lutheran Communities of the Russian State provided assistance to Estonian and German villages in the region for building school-prayer houses and hiring sacristan-school teachers.

In 1887, the construction of the settlement of Estonia's school-church was completed. Jaan Kilk, Peeter Pint, and Jüri Korbmann made the most significant contributions to the construction of the school building. The construction cost 1,000 rubles, of which 200 were given by the assistance fund, 200 were borrowed from the Russian Orthodox monastery in Dranda, and the rest was donated by the villagers. The school building had a classroom that also served as a prayer hall, two living quarters for the sacristan-school teacher, a storeroom, a kitchen, and a corridor. Since the school was also a prayer house, in addition to benches, desks, and boards, an altar, a pulpit, and an organ were step by step provided, and later a bell tower was erected in the yard.

To be continued…