Samurzakanians or Murzakanians by Simon Basaria

Abkhazians from Samurzakan region

Published: ‘Materials on the history of Abkhazia’. Sukhum, 1990. Issue 1. pp. 29-30.

Simon Basaria (1884-1941)

After a long period of kings, Abkhazia began, beginning in the 17th century, to be ruled by sovereign princes from the Chachba family (in Georgian ‘Shervashidze’). The first ruler of this family was Kvap. He had heirs: Rosto, Levan and Murza-khan (oriental style) — in Abkhaz ‘Murzadan’ or ‘Murzakan’. After the death of Kvap, Abkhazia began to be ruled by his eldest son, Rosto, who gave one brother, Levan, the portion of Abkhazia from the R. Kodor to the R. Okhurej (i.e. Abzhua [= ‘the middle’ — ed.]), and to another, Murzakan, from the river Okhurej to the R. Ingur. Since then, this part of Abkhazia began to bear the name of its ruler, thus coming to be called ‘Murzakan’ or ‘Samurzakan’; the Abkhazians under this jurisdiction began to be called ‘Murzakanians’ or ‘Samurzakanians’, just like the Abkhazians of the Gudauta District (‘Gudautans’ or ‘Bzypians’), of the Dal region (‘Dals’), of the Tsebelda region (‘Tsebeldans’), of the Gagra region (‘Gagrans’), etc… Such territorial designations of certain regions of Abkhazia misled many ethnographers and historians not well versed in the matter. The confusion reached the point of absurdity: some distant tribes appeared (Zebeldin, Bzyp, Samurzak) and there were as many such tribes as there were separate territorial districts and regions in Abkhazia. Meanwhile, all of them were inhabited exclusively by Abkhazians, who take their national line back many centuries before the birth of Christ. This was the situation in which the Samurzakanian Abkhazians also found themselves, ultimately renamed by the ‘Divine Grace’ of Nicholas I (1840) the ‘Samurzakanian tribe’ – ‘obligingly disposed’ to him, (as stated in the Tsar’s deed addressed to Samurzakanian Abkhazia) ‘for the inherent exemplary courage shewn by their militia in a detachment against the Dals, for the establishment of peace in Dal’. ‘In commemoration of the blessing’ of the Tsar, they were granted a banner ‘which was ordered to be used in the service of the autocrat with fidelity and zeal’.

This shameful banner and deed, shameful and vile from the standpoint of the State, which was not above utilising any means to set brother against brother, sad and sorrowful from the standpoint of the Samurzakanian Abkhazians, eager for the ranks, aiguilletes, medals and crosses of their leaders, who took up arms against their kin – the Dals – these knights without fear and reproach, these carriers of bright truth in upholding their sacred rights, yes these regalia of the Russian despot are still kept in the heart of Samurzakania!

The author of the book ‘Guide to an Understanding of the Caucasus’, travelling around the Caucasus and passing through Guria, Imereti(a) and Mingrelia, visited Samurzakan in the first years of the 19th century. He begins his description as follows: “Samurzakan, now a Russian region, starts at the [River] Ingur; it has inhabitants of completely different manners from the Mingrelians. This country is still disputed between Abkhazia and Mingrelia: in terms of position, language and the generation of inhabitants, it is an integral part of Abkhazia.” The author further writes about the claim of the Dadiani princes to this region of Abkhazia. He says: “Mingrelia, knowing Russia’s love for it, petitioned in favour of this country being confirmed as belonging to it.” “The pretext for this has become manifest,” continues the eyewitness-author. “Commander-in-Chief General Rosen annexed Samurzakan to Mingrelia. Prince Levan Dadiani reported that in ancient times Samurzakan had undoubtedly belonged to his ancestors, but circumstances had given it the opportunity to tear itself away and join Abkhazia. Samurzakan served as a reward for Dadiani’s allegiance,” concludes the author.

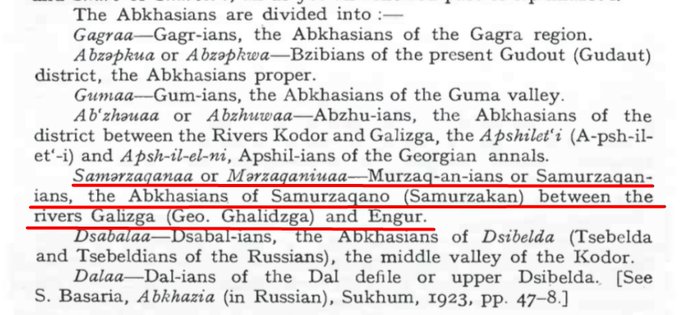

Georgica (Journal of Georgian and Caucasian Studies) Vol. 1 October 1936. (p.54). 'Ethnographical and Historical Division of Georgia' By A[ndrei] Gugushvili

Now the sense and enigmatic reasoning behind such a unification of Samurzakan with Mingrelia is clear: obviously, according to just one “parti pris assertion” by Prince Dadiani that Samurzakan had allegedly belonged to his ancestors, Rosen could not issue an order to join it to Mingrelia — after all, Dadiani could have made the same “parti pris assertion” with respect to Kabarda, Chechenia, and Daghestan. Here, simply the imperialist plans of Russia demanded that Dadiani ‘make a parti pris assertion’, and that, thanks to ‘its devotion to Russia’, Samurzakan be annexed to Mingrelia (i.e. in essence to Russia, since Mingrelia was already the province of the Russian Tsar). How did the population react to this act of union? The eyewitness continues: “But the Samurzakanians did not assent, and, hating the newly established power, they beat and drove off the Dadiani officials. ‘We are Abkhazians, not Mingrelians, why make us subservient to that power?’, which they did not know and did not want to know. ‘Let the laws of Dadiani make his subjects miserable — that’s enough for him; Russians will surely never come to our mountains!’.” This is how the author captures the indignation of the population, living, as he did, among the Abkhazians at this alarming time. We continue quoting the information provided by this invaluable eyewitness:

“Assuring each other in this way, they hastened across the Ingur into Mingrelia, to Zugdidi, drove off Dadiani’s flocks and took people into captivity. In a word, they wilfully declared war on Dadiani. There was no end to such pranks. Dadiani only made threats,” the author continues, “but was not able to punish the Samurzakanians; they just laughed at his weakness and said: ‘Let him come[1] to test our sabres and bullets — the first are sharp, the second are true.’ The riots intensified, and therefore the Russians, having entered under the command of General Akhlestyshev inside their borders, immediately brought them into subservience,” concludes the author. As to the further course of this issue, he writes:

“The Samurzakanians, humbled before Russian power, nevertheless did not recognise Dadiani. They said: ‘Cut as you may, we know no other ruler but our freedom; we are Abkhazians, not Mingrelians’.” The eyewitness-author furthermore says: “Such was the determination of the Samurzakanians, in spite of exhortations and force, until the issue was resolved and it was turned into a Russian region, under the direction of a governor resident in Vedi,” the author concludes. Of course, this was what the Russian conquerors needed: they created the pretext for subjugating this region of Abkhazia. After that, the Russians forced the Samurzakanians to commit the greatest villainy with respect to their Dal brethren. About the motivation here the author writes: “The Russian Tsar, loving it (i.e. Samurzakan), as a native, gave its name to the region, granting it as a reward of fidelity and devotion (besides many awards to the people) another banner. Now the Samurzakanians, living under the laws of the Russians, no longer trouble the Mingrelians,” are the words with which the author closes his interesting reports of events of which he was an eye-witness 80 years ago.

In the political sense, the Mingrelians are just as Russian as the Muscovites, and in the same direction they can influence every tribe in contact with them, a striking proof of which is the fact, recognised by our opponent, that due to the influence of the Mingrelians, the Samurzaqanoans are a branch of the Abkhazian tribe, – being in constant communication with the Mingrelians, they became completely Russian subjects and during the repeated uprisings of their fellow tribesmen did their best to help the government in suppressing disturbances and pacifying the rebels.

― Jakob Gogebashvili (Who should be settled in Abkhazia?, Tiflisky Vestnik, 1877)

Samurzakan - Photo by Dmitri Yermakov (1846 –1916).

+ Who are the Mingrelians? Language, Identity and Politics in Western Georgia, by Laurence Broers

+ Abkhaz Loans in Megrelian, by Vyacheslav Chirikba

+ Yet a third consideration of Völker, Sprachen und Kulturen des südlichen Kaukasus, by George Hewitt

Such, then, is the brief story about how the population of this eastern part of Abkhazia, a nation as traditional as all Abkhazians in defending their age-old militarism, was renamed by the Tsar’s chancellery ‘a Samurzakanian tribe’, an entity which in essence does not exist, not for history, not for ethnography, and not for linguistics; but then, how many pretexts were fabricated for an offensive nationalism, so that the manufactured situation could be used for an accelerated conducting of all kinds of assimilation ‘with the free spirit of the people’, to quote Seleznev’s phrase. The intrigues and parti pris assertions of the trans-Ingur adherents of Russian autocracy severed freedom-loving Samurzakan from all the rest of Abkhazia, which was then still free, and made it a ‘bailiwick’ of the sovereign Tsar. The Dadiani officials, priests, teachers, community-scribes, officers, etc., who had hitherto been exiled, were all trans-Ingur residents and had already become accustomed to governmental procedures. How is the work of this warm, homogeneous company manifested? The author of the book ‘Abkhazia is not Georgia’ provides a detailed answer of the surprisingly methodical, persistent, quick, coordinated implementation by them of all assimilation-techniques. Samurzakanians gradually begin to forget their native language, the Abkhaz language, and had to learn a language that was so necessary for conversation with the bureaucratic world, with governors, with officers and with clergy.

Transcaucasian Boundaries, by John Wright, Richard Schofield, Suzanne Goldenberg (2003).

In the book ‘Abkhazia is not Georgia’ and in the work of K. Machavariani, interesting facts are adduced relating to the remodelling of Abkhazian surnames in Samurzakania according to the Mingrelian style. We cite this in full, especially since such a reworking is to be observed throughout Abkhazia. Abkhazian surnames appear first:

Achba - Anchbaja (Anchabadze)

Chachba - Sharashia (Šervašidze)

Marshan - Marshania

Emkhi - Emukhvari

Chabalurkhwa - Sotiskua (Sotishvili)[2]

Dzjapsh-ipa - Dzepshskua (Dzeishvili)

Inal-ipa - Inaliskua (Inalishvili)

Maan - Margania

Lakra - Lakerbaia

Zhwan - Zhvania

Akirta - Akirtava

Eshba - Eshbaia

Mikamba - Mikambaja

Kilba - Kilbaja

Vardan - Vardania

Shamba - Shambaja

Kapba - Kapbaia

Kakuba - Kakubava

Zukhba - Zukhbaia

Shakryl - Shakirbaja, etc.

We would once again draw the attention of the respected Prof. Khakhanov in regard to this circumstance and would pose him the question: Who assimilated whom? Whose ‘more flexible language’ absorbed the less accessible? It's a shame that people of scholarship, as also leaders of a state’s destiny, have gone so far in the field of national aspirations that they are in complete contradiction with all other cultural and scholarly ideals. Indeed, in the end, national sentiment can fall into the category of instincts that are so characteristic of the animal world, and therefore, if the mind is not in control of it, it transmogrifies into ‘zoological nationalism’.

One way or another, aggressive nationalism in Abkhazia was applied and received surprising and sad expressions here, with the result that even now the greatest caution is required, together with the greatest justice for its further resolution. That is why it is necessary once again to note the wisdom of the Revolutionary Committee of Abkhazia in making its declaration of the Republic of Abkhazia.

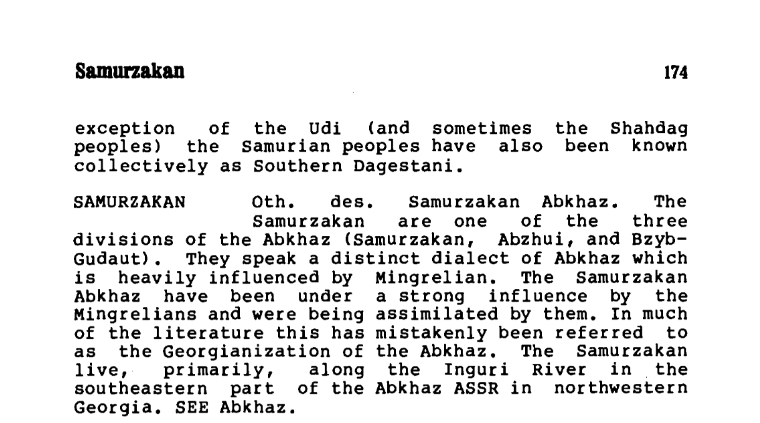

Peoples of the USSR An Ethnographic Handbook By Ronald Wixman (2017).

What kind of operation did the adherents of offensive nationalism conduct in Samurzakan? After the Russian Revolution, when the Abkhazian people clearly revealed their national existence (so unpleasant for Georgian chauvinists) and began to conspire with the Samurzakanian population about joining the union of united highlanders, then at the complaint of local priests, these sheikhs from Orthodoxy, and other agents of the Tiflis chauvinists, there followed an order to separate Samurzakan from Abkhazia and join it to the Kutaisi Province, subordinate to the provincial commissar V. Chkhikvishvili. But in view of the protest of the population of this region and its refusal to submit to a foreign provincial commissar, two months later, Samurzakan was again returned to its normal place. Prior to this, the Samurzakanian clergy had separated from the Abkhazian bishopric and recognised the Catholicos of Georgia. In 1918 Georgian schools opened in all the villages of Samurzakan. The Abkhazian People’s Council (first convocation), responding to all the aspirations and views of the Abkhazian people, reacted with complete indifference to all this work of the aggressive nationalists, reasonably allowing the Samurzakan population to react as they pleased.

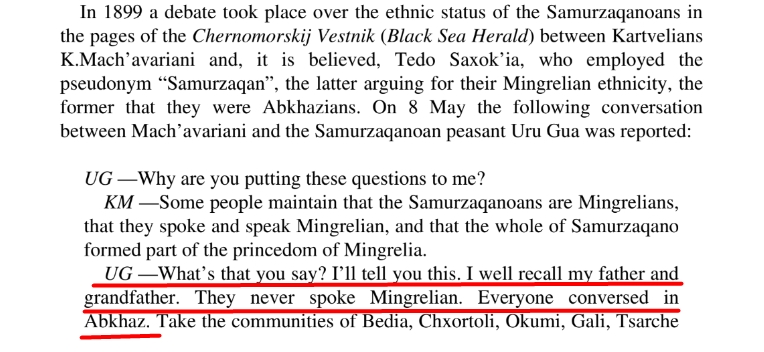

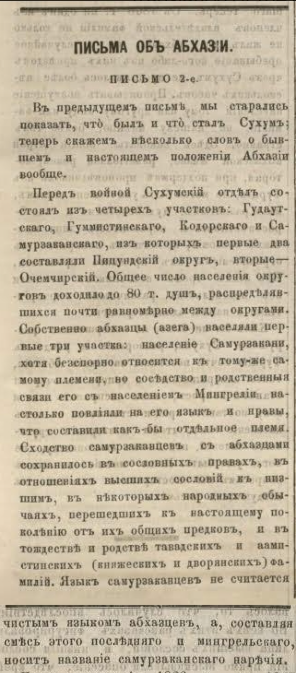

from The Newspaper "Kavkaz" 1877 - No 222

Translation:

In the previous letter, we tried to show what Sukhum was and what it has become; now let us say a few words about the former and present situation of Abkhazia in general.

Before the war, the Sukhum District consisted of four sections: Gudauta, Gumista, Kodori, and Samurzakan, of which the first two formed the Pitsunda District, whilst the latter two formed the Ochamchira District. The total population of the Districts amounted to 80 thousand souls, almost evenly distributed among the Districts.

The Abkhazians proper (the Apswa) inhabited the first three regions: the population of Samurzakan, although undoubtedly belonging to the same tribe, was influenced by proximity to, and kinship-ties with, the population of Mingrelia in its language and customs to such an extent that it formed, so to say, a separate tribe.

The similarity of the Samurzakans with the Abkhazians was preserved in the class-rights, in the relations of the higher classes to the lower ones, in some folk-customs that have passed down to the present generation from their common ancestors, and in the identity and kinship of the Tavad and Aamsta (princely and noble) families. The language of the Samurzakans is not considered to be the pure Abkhazian language, but, being a mixture of the latter and Mingrelian, it is called the Samurzakan dialect.

The conscientious forces of Samurzakan, with the exception of one or two renegades, ‘lads’ of the Tiflis ministers, expressed clear lack of sympathy for all this. All of them said that the Samurzakanians were Abkhazians, and therefore they found their territorial and cultural rejection from the whole of Abkhazia to be the greatest injustice; everywhere they protested, pointing out the madness of the Tiflis chauvinists, who were excessively carried away by foul national[istic] aspirations and were therefore going against the elementary rights of the Abkhazian nation.

Such enlightened Samurzakanians as the engineer Kakuba, the barrister Zukhbaja, the learned forestry specialist Gamisoni, Dr. V. Achba, E. Eshba, N. Akirtava and many male and female students did not absolutely share the policy of the aggressors in relation to Samurzakan.

Not the least wild act of the chauvinists was the question of the nationalisation of schools. The Sukhum teachers’ seminary, where sons of all Abkhazia’s ethnic groups studied, was nationalised, and therefore the entire course was conducted for Georgians in Georgian, and for the Abkhazians in the Abkhaz and Russian languages; Samurzakanian pupils were obliged to pass through in Georgian.

[1] Seleznev, passing Anaklia in the 40s, writes: “Abkhazia earlier began from Anaklia, whose ruler, Murzakan, had a residence here in the 17th century.”

[2] Forms ending in -dze and -shvili are Georgian (not Mingrelian) — ed.