Abkhazia and The Caucasian War: 1810-1864, by George Anchabadze

George Anchabadze (Achba)

Professor of history at the Ilia State University, Georgia.

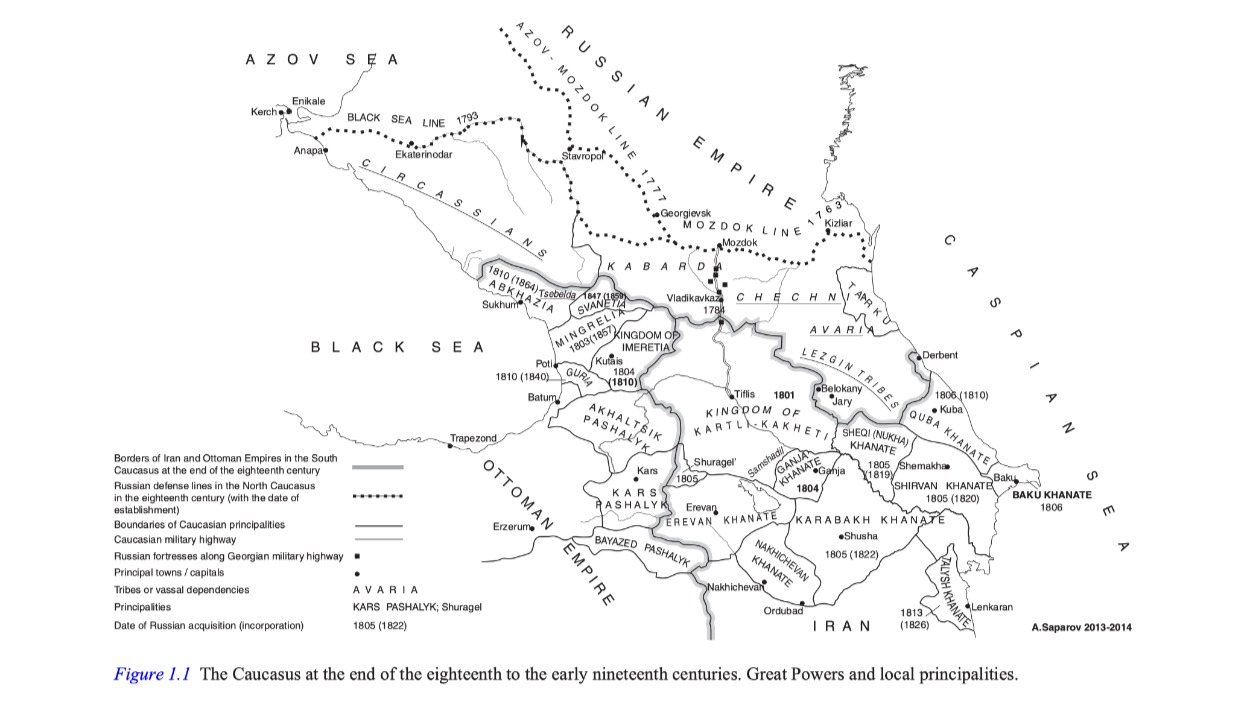

The Caucasian War is the longest-running military conflict in Russian history. One of its features is the absence of generally accepted chronological boundaries. Moreover, if almost all historians recognize 1864 as the final date of this conflict, then there is a wide range of opinions regarding the initial date - 1722, 1763, 1785, 1801, 1817, 1830 and other years. Each of these dates has its own more or less justifiable motives, but the most reasonable is the opinion of historians who attribute the beginning of the great confrontation in the North Caucasus to the era of the Russian Empress Catherine II (1762-1796), when the active advance of the Russian troops and administration began here.

At the time in question, Abkhazia was a principality headed by the house of Chachba, or Shervashidze. There were also numerous nobility of various degrees in Abkhazia. The most powerful noble clans were only in nominal dependence on the supreme ruler of the country.

It is believed that from about 1578 the Abkhazian principality was a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, but this dependence was not strong and permanent. So, in 1806, Prince Keleshbey Chachba-Shervashidze[1] broke off relations with Turkey and established ties with the Russian military command in the Caucasus, although he was in no hurry to become a Russian citizen. In such a situation, in 1808, the Abkhaz ruler was killed under unclear circumstances. Keleshbey's successor was his eldest son Aslanbey, an opponent of rapprochement with Russia.

ESTABLISHMENT OF A RUSSIAN PROTECTORATE OVER ABKHAZIA AND PEOPLE'S RESISTANCE (1810-1830)

In July 1810, a Russian squadron fired at the Sukhum fortress and landed troops, which captured the city in battle. Aslanbey fled to the Sadz, an Abkhazian tribe that lived between the Bzyb and Sochi rivers. The Russians proclaimed the ruler of Abkhazia his younger brother George, who took over the Russian protectorate.

As part of the Russian Empire, the Abkhazian principality – where Georgy Chachba-Shervashidze ruled, and then successively his sons, Dmitry and Mikhail – occupied a much smaller territory than in the previous period. The mountain cantons of Abkhazia - Tsabal, Dal, Pskhu and others, did not accept the supreme patronage of Russia and refused to obey the ruler - the Russian protege.

As for the political situation in the territories subject to the ruler - coastal Abkhazia, it did not inspire confidence in the Russian authorities. The situation became especially complicated after the death of Prince George, in February 1821. Soon, the resistance movement was headed by the former ruler Aslanbey, who hastily returned to his homeland.

To suppress the uprising, the ruler of Imereti (Western Georgia), General Gorchakov, entered Abkhazia with military forces, defeated the rebels, and pursued them to the Bzyb River. Aslanbey again went to the Sadz. Gorchakov proclaimed Dmitry Shervashidze, the eldest son of the deceased ruler as the prince of Abkhazia but Dmitry soon died (according to the official version, he was poisoned) and his younger brother, 17-year-old Mikhail, was approved as the sovereign. But the power of the young prince was even weaker. The unrest continued in the country, which grew into an open uprising in 1824. Gorchakov's new campaign did not have a decisive success and the Russian troops were forced to leave Abkhazia, keeping only the Sukhum fortress. Together with them, the young ruler and his household left. After the departure of the Russians, the liberation struggle in Abkhazia escalated into an internecine war of local feudal lords.

+ Book in Russian: Abkhazia and the Caucasian War: 1810-1864, by George Anchabadze

+ Lapinski: Abkhaz people are the last in the Caucasus who still put up resistance to the Muscovites

+ 21 May 1864: From Dmitri Kipiani to Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich Romanov

+ The solitude of Abkhazia, by Douglas W. Freshfield (1896)

+ Essays on eastern questions: The Abkhasian insurrection, by William G. Palgrave

+ Mr Palgrave in the Dismal Swamp | The Pall Mall Gazette, 1867

+ Conquest and Exile, by Austin Jersild

WESTERN CAUCASUS AT THE CROSSROADS OF HISTORY (1830-1853)

The Ottoman government, which for a long time did not recognize the transition of Abkhazia to the rule of the Russian Empire, after the defeat in the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829 was forced to come to terms with this fact. According to the peace treaty (1829), the Ottoman Empire, in addition to its Transcaucasian possessions, also ceded to Russia the rights to the lands of the Northwestern Caucasus (from the Kuban to the Black Sea and the Bzyb River), which it actually never owned. The population of this region consisted mainly of the peoples of the Adyghe-Abkhaz ethnic group: Adygs (Circassians), Ubykhs and Abkhaz ethnic groups independent of the Abkhaz ruler (Sadz, Medovey, etc.). Thus, Russia received the formal rights to conquer independent Circassia (at that time, so was called not only the territory of the Circassians, but other peoples of the North-West Caucasus as well). By order of Emperor Nicholas I in 1830, the Russian army stepped up military operations in this direction. This meant that since 1830 in the Caucasus there were already two centers of mountain resistance, which were essentially independent theaters of military operations: 1) eastern - Chechnya and Mountainous Dagestan, where at that time a centralized state - the Caucasian Imamate was taking shape, and 2) western - the settlement zone of the Adyghe-Abkhaz peoples of the North-West Caucasus. In the 1830s two confederations were formed there which had one goal - to defend independence. The first included the Adyghe tribes - Natukhai, Abdzakhs and part of the Shapsugs. The second alliance was made up of another part of the Shapsugs, Ubykhs and the Western Abkhazian groups - Sadz and Medovey (several cantons in the northwestern mountains of historical Abkhazia). The leaders of this association were the Ubykhs.

The Ubykh and Abkhazian leaders in the Sochi valley 1841, drawn by Prince G. G. Gagarin.

In the summer of 1830, General Hesse landed in the Sukhum Bay with a detachment of troops. The purpose of the expedition was to establish Russian control over the coast of Abkhazia and Circassia. However, the forces allocated for this (2,400 soldiers) were completely insufficient. Hesse's troops advanced only as far as Gagra (on the western border of Abkhazia) and entrenched themselves there, building a fort. In Abkhazia, weakened by civil strife, the restoration of Russian suzerainty was relatively easy. In negotiations with Hesse, the Abkhaz feudal lords agreed to get back under the supreme power of Russia providing the preservation of their hereditary rights and privileges. Otherwise, they threatened with a new uprising. Hesse, who had instructions to do everything possible to resolve the issue peacefully, accepted these demands.

The restoration of the Russian positions in Abkhazia strengthened the position of the sovereign Mikhail, who since 1830 had firmly settled down in the country. On the other hand, his increased authority, the qualities of a ruler and personal ties with the mountain aristocracy helped a lot the Russians in many ways in such a difficult region as the North-Western Caucasus - the western theater of the Caucasian war.

The war in the Western Caucasus became protracted. Therefore, after the death of the first Dagestani imam Gazi-Muhammad in 1832 and the fall of his stronghold, Gimry, the Russian high command, believing that organized resistance in the Eastern theater was over, shifted the center of gravity of hostilities to the Western theater. However, despite the increase in the number of imperial troops in the Caucasus (by 1837 - 154,000 soldiers), attempts to extend military control over Circassia ran into serious obstacles. The Russian Minister of War Chernyshev in 1840 was forced to state: "Long-term actions by force of arms against the recalcitrant Circassian tribes... had no effect on the general pacification of the region."

The intensification of hostilities in Circassia coincides with the strengthening of the Russian military presence in Abkhazia, which, of course, was not a coincidence. New fortifications and strongholds of Russian troops appeared in the principality, but it was still far from the real subordination of Abkhazia.

In Tsabal, conquered by Russian troops in 1837, an uprising broke out three years later. The partisan war lasted until 1845, when part of the rebels entered into negotiations with the Russian authorities and, having received forgiveness, returned to a peaceful life. But the rebel leader, Prince Eshsou Marchand, did not lay down his arms; retreating to the rebellious Pskhu, he, together with the remaining soldiers, continued the struggle, acting now in Dal and Tsabal, in Coastal Abkhazia, now in the North Caucasus.

The Caucasian War reached its climax in the 30s and 40s of the 19th century. The Imamate, which was considered defeated after the death of Gazi-Magomed, revived again. In 1834, Shamil was elected imam and he deployed a successful guerrilla warfare against the regular troops. In 1839 the main forces of the Russian Caucasian corps were moved to the eastern theater of war. But Shamil, supported by the Chechens, launched a counter-offensive and cleared most of the mountainous Dagestan from the tsarist troops. Russian troops temporarily went on the defensive, although their total number in the Caucasus by 1844 had already reached 185,000 people.

![A report from Abkhazia [Abchasia]: Reading Mercury - 07 December 1839 A report from Abkhazia [Abchasia]: Reading Mercury - 07 December 1839](/aw/images/archives/Reading_Mercury_Dec_7_1839.jpg)

A report from Abkhazia [Abchasia]: Reading Mercury - 07 December 1839.

In April 1846 Shamil with 10,000 mountain-dwellers invaded Kabarda to unite with the Adygs and form a common front of struggle from the Caspian to the Black Sea, but the Russians forced him to retreat. The imam, however, did not abandon attempts to expand his influence in the Western Caucasus. In the 40s its representatives appear here, the most notable of whom was Magomed-Amin, an Avar by nationality. Abdzakhs invited him to Circassia, asking Shamil to give them a worthy leader. Magomed-Amin secretly arrived from Chechnya in 1848. Abdzakhs and other Adyghe tribes rallied around him.

Formally being the naib (governor) of Shamil in Circassia, Magomed-Amin, due to geographic disunity with the Imamate, actually independently waged a war with the Russians and ruled over the territory, which during 1848-1859 varied depending on various factors. By the spring of 1853, the orbit of Magomed-Amin's influence reached its maximum, covering almost the entire North-Eastern Caucasus. At this time, it was also recognized by the Ubykhs, Medovey and some Sadz cantons. The head of the Tsabal rebels, Eshsou Marshan, also closely cooperated with the Naib.

CRIMEAN WAR. THE END OF THE CAUCASIAN WAR AND ABOLITION OF THE ABKHAZ PRINCIPALITY (1853-1864)

At the end of 1853, the Eastern, or Crimean War began, in which a coalition of England, France, Turkey and the Sardinian kingdom acted as Russia's enemy. The hostilities were conducted in isolated territories, far from each other, but the main theater of the war was the Crimean peninsula and the Black Sea coastal area as a whole.

The Eastern War revealed the military and economic backwardness of tsarist Russia. The appearance on the Black Sea of the Anglo-French squadrons, which had a military-technical superiority over the Russian fleet, dramatically changed the situation in the main theater of operations in favor of the coalition. Russian coastal fortresses in the Eastern Black Sea region, facing the threat of a double blow from the allied fleet and mountain-dwellers in the spring of 1854, by order of Nicholas I, were hastily evacuated, and the fortifications were blown up.

Mikhail Shervashidze rendered great assistance to the Caucasian command in the organized withdrawal of Russian troops from Abkhazia. The barriers put up by him ensured the safe passage of the columns, which were threatened by the attack of the hostile mountain-dwellers. This operation was highly appreciated in St. Petersburg; the Abkhazian ruler was awarded the Order of the White Eagle of the Russian Empire. However, then events occurred that cast a shadow on him in the eyes of high officials.

Taking advantage of the departure of the Russians, Turkish troops began to land in Abkhazia. Mikhail initially wanted to resist the enemy and asked for military assistance, but the main command could not allocate forces. The main part of the troops in the Caucasus (by then 270,000 soldiers and officers) was still chained to the front of the struggle against the mountain-dwellers. The prince realized that Abkhazia was being abandoned to the mercy of fate, but until the outcome of the war was determined, he was in no hurry to take decisive steps. Only in April 1855, against the will of his superiors, he returned to Abkhazia, occupied by the Turks, where he met with the Turkish Marshal Omer Pasha.

"Prince Michael of Abkhasia (Hamid Bey)" - taken page 90 of 'The Trans-Caucasian Campaign of the Turkish Army under Omer Pasha. A personal narrative' by Laurence Oliphant (Edinburgh,1856).

This step by Mikhail Chachba-Shervashidze shows his serious discord with the Russians. The Turkish sultan, wishing to win over the Abkhazian ruler, granted him the title of Pasha and other advantages, but Mikhail did nothing for the Turks. He continued to keep in touch with Tiflis, showing that he continues to look after Russia's interests. The population of Abkhazia met the Turks rather coldly. Although some of the Abkhaz served them, the other part fought on the side of the Russians.

The main events of the Eastern War unfolded around Sevastopol, but the allied command did not forget about the North Caucasian direction, planning a landing in Circassia in order to push the Russians north from the Kuban and Terek with the help of the mountain-dwellers. But the Circassians, tired of the long confrontation, did not provide active assistance to the coalition troops. When the Russians in 1854-1855 without a fight left their advanced positions and went beyond the Kuban, they considered that there was no need for a war.

Such sentiments created a threat to the military-political unification of Magomed-Amin, especially in the seaside, where the positions of Islam were weak. Here, not everyone liked the imposition of strict Islamic orders, but put up with it in the interests of the common struggle. After the departure of the Russians, everything changed, in Ubykh and Shapsugia the Islamic institutions created by the naib ceased to function, and the judges and chiefs appointed by him were expelled.

The Eastern War ended with the defeat of the Russian Empire. The Paris Peace Treaty (1856) limited Russia's sovereignty in the Black Sea and weakened its influence in the Balkans and the Middle East, but it retained its position in the Caucasus.

After the news of the conclusion of peace came, the Abkhaz princes and nobles, chaired by the ruler, held a meeting on how to return to the rule of Russia, avoiding punishment. Then Mikhail Shervashidze went to Tiflis to settle the problem. Despite the fact that the Abkhaz ruler irritated the Russian authorities with his behavior during the war, in St. Petersburg they decided to hush up this issue for a while, while the struggle with the mountain-dwellers continued, and not to remove Mikhail from power. The investigation of the case of his "treason" was terminated under the pretext that "the sovereign did not find direct evidence of a deliberate, purposeful, calculated betrayal." The Abkhazian feudal lords who collaborated with the Turks were also forgiven in order to use them at the final stage of the Caucasian War. Thus, the issue was settled and in July 1856 Russian troops landed in the Sukhum harbour, led by Mikhail Chachba-Shervashidze.

In July 1856, Emperor Alexander II appointed Adjutant General Baryatinsky as governor and commander-in-chief in the Caucasus, to whom he subdued enormous forces - over 350 thousand soldiers and officers. Baryatinsky first directed his main efforts against Shamil, deploying a 200,000-strong group around the Imamate. In the summer of 1859 gradually tightening the blockade ring, Russian troops surrounded Shamil on Mount Gunib, where, after hopeless resistance, the famous leader of the mountain-dwellers personally surrendered to the governor and was sent to Russia.

Annexation of the Caucasus 1800 - 1864. "History of the USSR. Vol. 7. The Russian Empire in the First Half of the 19th Century." (Moscow, 1947).

After the fall of the Caucasian Imamate, the attention of the Russian High Command turned to the North-West Caucasus, where main attack force of the Caucasian army, battle-hardened with Shamil's detachments, was transferred to reinforce the troops located in the Kuban. In November 1859, Magomed-Amin, realizing the futility of further resistance, laid down his arms. Accompanied by 2,000 horsemen, he came to the Russian military camp and swore allegiance to the emperor. This fact could serve as a precedent for a compromise peace in an age-old war, but in the ruling spheres of the empire, not everyone considered it acceptable for reasons of prestige. The majority of the Caucasian generals headed by Baryatinsky also strongly opposed it. According to their plan, in order to exclude the possibility of a new uprising, the mountain-dwellers should have been resettled to the steppe, far from the sea, and the mountains had to be populated with Cossacks.

In the fall of 1861, Alexander II visited the North Caucasus. He twice met with mountain delegates who declared that they were ready to recognize Russian citizenship on the condition that they stay on their lands and preserve their autonomy. Alexander rejected these conditions, demanding unconditional submission and eviction to the plane. Otherwise, the mountain-dwellers were asked to leave for the Ottoman Empire, which expressed a desire to accept the Caucasians.

Only a small part of the mountain-dwellers agreed to settle on the plains, while the majority decided to fight for their land. The war resumed with a huge disparity of power. A systematic attack on Circassia began, accompanied by deforestation, the destruction of villages and the expulsion of people from their homes.

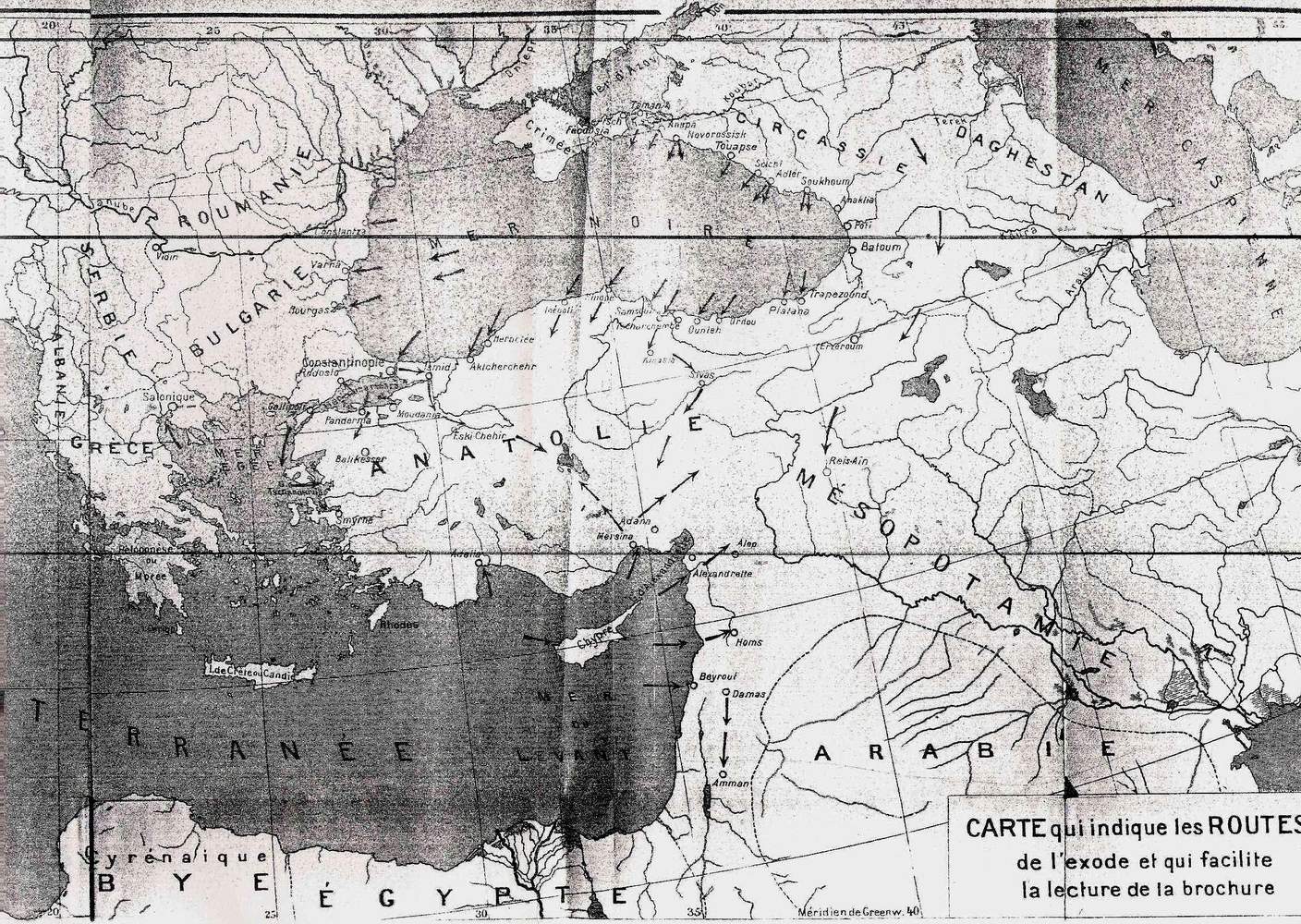

In 1864, the resistance of the Circassians, already displaced from their original habitats, was broken. Under the threat of starvation or total extermination by the troops, they began to leave for Turkey in droves. The government settled the lands left by the mountain-dwellers with Russian colonists.

After the defeat of the Circassians, it was the turn of the Ubykhs. Having suffered defeat in the last battle on March 19, 1864, the proud Ubykhs had to show submission under the condition of being exiled to the Ottoman Empire. Sadz surrendered after the Ubykhs.

The last volleys of the Caucasian War thundered in the mountains of Western Abkhazia. The inhabitants of Medovey, together with the representatives of different tribes gathered there, prepared for the battle. The new Governor General of the Caucasus Viceroyalty Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich (brother of Alexander II) sent four columns of troops totaling more than 25,000 soldiers to this hard-to-reach region. The troops, moving from different directions, decisively suppressed the last centers of resistance and concentrated in the valley, which is now called Red Glade. Here on May 21, 1864, in the presence of Grand Duke himself, a thanksgiving prayer was served to commemorate the victory and a solemn parade of troops was held. This day is considered to be the end of the Caucasian War - the longest military conflict in the history of Russia.

Expulsion of Circassians & Abkhazians to the Ottoman Empire. "Les Russes en Circassie, 1760-1864" A. Méker. (Berne 1919).

When official Russia was celebrating victory in the Caucasian War, the mountain-dwellers, “defeated but not conquered,” as one of the contemporaries of this event wrote, left their native land in droves and went overseas. This mass emigration of Caucasians began in the middle of the 19th century, and in the 60s took on catastrophic proportions, turning into a real tragedy for the Adyghe-Abkhaz peoples, whose number of those who left far exceeded the number of those who remained on their native land. The Ubykh people disappeared from the map of the Caucasus, completely resettling to Turkey in 1864. At the same time, Sadzs and Medovey, as well as most of the North Caucasian Abaza, moved out almost completely. Most of the Adygs (Circassians), until that time the most numerous North Caucasian ethnic group, also left.

Since the end of the 50s of the 19th century the Russian government began a phased abolition of the protectorates remaining in the Caucasus. The Abkhazian principality was one of the last to be abolished, as the war with the mountain-dwellers continued in its neighborhood and the authorities feared an Abkhaz uprising that could complicate the situation in the region. Only in April 1864, Mikhail Shervashidze, recognized as "unreliable", was removed from power, and soon after that direct Russian rule was introduced in Abkhazia.

The government's decision to abolish the autonomous status was carried out without incident. The former ruler, who had grown old and sick, was arrested in November 1864 under a far-fetched pretext and deported to Russia, although in commemoration of his past merits he was given a good pension and left the rank of Adjutant General and the title of "Most Serene Prince". Mikhail Chachba-Shervashidze died in Voronezh in 1866. His body, according to his will, was transported to his homeland and buried with honors in the ancient cathedral.

[1] The surname of the sovereign princes of Abkhazia in the Abkhaz language is "Chachba". However, in the sources and literature of the 19th century, its Georgian form "Shervashidze" (known from the 12th century) is more common. This form is not used in the Abkhaz language. However, there is no semantic difference between the terms “Chachba” and “Shervashidze,” these are two designations of the same historical genus.