The Distortion of Abkhaz Surnames

This article examines the historical processes that have shaped the demographic, linguistic, and cultural identity of Abkhazia. It explores the distortion of Abkhaz surnames, the influence of external forces on local identities, and the impact of administrative and religious policies on cultural heritage. Particular attention is given to the Samurzakan (Myrzakan) region, where interactions with neighbouring Georgian and Mingrelian communities further complicated the narrative of ethnic identity. Using archival materials, historical accounts, and scholarly works, the article highlights the lasting effects of these transformations on Abkhaz national identity.

Throughout history, there has been a consistent pattern of population movements, including reciprocal migrations, between the Abkhaz and neighbouring communities. These migrations were primarily influenced by political, economic, and social processes, often driven by a variety of factors such as wars, blood feuds, conflicts among the owners of privileged estates, escapes from feudal lords, customs, and the search for new lands. During the period of the Abkhaz Kingdom (8th–10th centuries CE), population movements were particularly intense, with expansion efforts extending deep into Georgian territory. During this time, migrations by feudal lords were followed by their dependents, who settled in their new locales and became permanent residents of western Georgia. Even in the place names of Kartli from that era, we encounter Abkhaz names, such as Achabeti (from Achba), Chachubeti (from Chachba), and Samachablo (from Achba).

Population movements were not confined to border regions but occurred across all areas. For instance, migrations from the Sadz region, the area farthest from Georgia, are evident today in the altered family names that have survived from that period. Examples include the Aubla family becoming Ubilava, Tsanba evolving into Tsanava, Jvüan into Jvaniya, Bagh into Baghbaya, Kakuba into Kakubava, Marshan into Marshania or Marshava, and Tsimtsba into Yirginava.

As mentioned above, a significant wave of Abkhaz migration occurred during the period of colonisation towards Georgia. During this time, the Abkhaz population that settled in western Georgian regions (Samegrelo, Svaneti, and Kutaisi, the former capital of the Abkhaz Kingdom) naturally merged with the local communities over time, adopting Georgian, Mingrelian, and Svan as their primary languages.[1]

Later, in reverse migrations, Georgian expansionism emerged, accompanied by what Andrei Sakharov referred to as the ambitions of a "Mini Empire." This trend brought with it efforts to "Georgianise" everything, including place names and surnames. These destructive and distorting practices targeting Abkhazia and the Abkhaz people escalated during the Menshevik occupation (1918–21) and evolved into oppressive and near-genocidal policies during the Stalin-Beria era from the late 1930s onwards.

The Stalin-Beria Era

Beginning in 1937, the head of the Georgian Communist Party, Lavrenti Beria, started what is referred to as his "anti-Abkhazian drive". This involved forced immigration of non-Abkhazians (especially Mingrelians) into Abkhazia and numerous other policies aimed at the forced assimilation of the Abkhaz. In 1938, Beria was transferred to Moscow, but these anti-Abkhazian measures continued under his successor.

A key component of this forced assimilation policy was the suppression of the Abkhaz language. The Abkhaz alphabet was changed to a Georgian base and all Abkhazian schools were closed, to be replaced by Georgian schools. This was part of a wider policy of suppressing minority languages that was being implemented across the Soviet Union at the time.

+ The Stalin-Beria Terror in Abkhazia, 1936-1953, by Stephen D. Shenfield

+ Documents from the KGB archive in Sukhum. Abkhazia in the Stalin years, by Rachel Clogg

+ On the Demographic Expansion of Abkhazia (1937 - Mid-1950s), by Adgur E. Agrba

A letter composed in 1947 by three Abkhaz – Giorgi Dzidzaria, Bagrat Shinkuba, and Konstantin Shakryl – that was sent to the head of the KGB in Sukhum, documented many of the discriminatory practices that the Abkhaz were experiencing at that time. The authors pointed out, for example, that the only Abkhaz language newspaper, Apsny Qapsh, was not a full four-page paper, unlike the other two regional newspapers in Georgian and Russian. They also described how the Abkhaz language had been removed from signage in state enterprises, organisations, industries, and trade departments. This, they stated, was done following a 1946 resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Abkhazian ASSR, although this resolution was never made public. The authors go on to point out that the use of the Abkhaz language in official franking had also been discontinued.

The letter also documented the poor state of the Union of Soviet Writers of Abkhazia, which, the authors claimed, did not have its own residence and was unable to publish its own works.The Abkhazian literary-artistic journal had also been suspended at the start of the war for “completely understandable reasons”, but after the war, requests by Abkhaz writers to restart publication were rejected. The Abkhazian Scientific-Research Institute in the name of Nikolai Marr (1864-1934) of the Academy of Sciences of the Georgian SSR also published nothing after 1940, even though it held “important scholarly investigations on the history and language of the Abkhazians”.

In October 1992, the State Archives and the Abkhazian Research Institute in Sukhum were destroyed by fire during the Georgian occupation. Before their destruction, portions of their contents were published in Abxaziya: dokumenty svidetel’stvujut 1937-1953. This book included much of the material referenced in the 1947 letter by Dzidzaria, Shinkuba, and Shakryl, offering additional details about the forced resettlement of non-Abkhazians into Abkhazia. The authors of the 1947 letter later addressed a similar appeal to Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev in 1953, after which they were rehabilitated. (See also: 'Abkhazia's Historical Struggles: A Historical Letter by Arkhip Labakhua and Ivan Tarba')

The systematic alteration and distortion of place names and surnames in Abkhazia became entrenched as state and religious policy throughout the 20th century. During the Stalin era, this policy extended beyond surnames to include the forced Georgianisation of geographical names and cultural institutions. Traditional Abkhaz place names were modified to fit Georgian linguistic norms, often erasing their original identity. For instance, the river Khipsta was renamed Tetri Tsqaro ("White Spring" in Georgian), the village Mikhelripsh became Salkhino, and Psirtskha (Novy Afon) was changed to Akhali Aponi ("New Athos"). The city of Gagra was divided into Akhali Gagra ("New Gagra") and Dzveli Gagra ("Old Gagra"), Atara was renamed Zemo-Atara, and Bzipta Gorge became Bzipis Khevi ("Bzyb's Gorge"). Bambora renamed Bambori, and Tamysh altered to Tamyshi.

Cultural symbols were not spared. The Abkhaz-Georgian choir, once a prominent representative of Abkhazian folk music and dance, was rebranded as "The State Ensemble of Georgian Folk Music and Dance," erasing its Abkhaz roots. These systematic efforts illustrate the extensive attempts during this period to suppress and reshape Abkhaz cultural and national identity. [See: 'Appendix to Documents from the KGB archive in Sukhum. Abkhazia in the Stalin years', Translation by B. G. Hewitt (1996)]

There is much to be said on this topic, but even a brief examination of practices in the Samurzakano (Gal) region provides sufficient insight into the overall situation. For this reason, let us briefly consider the writings of Prof. Timur Achugba on this subject.

The Distortion of Abkhaz Surnames [2]

In addition to various factors such as migration, the prevalence of interethnic marriages, and linguistic transformation, the deliberate distortion and replacement of Abkhaz surnames with Georgian ones significantly impacted the national identity of the region’s indigenous population. Particularly, Abkhaz surnames ending with the suffix "ba" (a variant of the Abkhaz term pa-ipa, meaning “son” or “descendant”) were altered by appending suffixes commonly found in Mingrelian and Georgian surnames, such as “ya,” “iya,” “va,” “wa,” “skua,” “dze,” and “shvili.”

Samurzakano (Myrzakan) Region

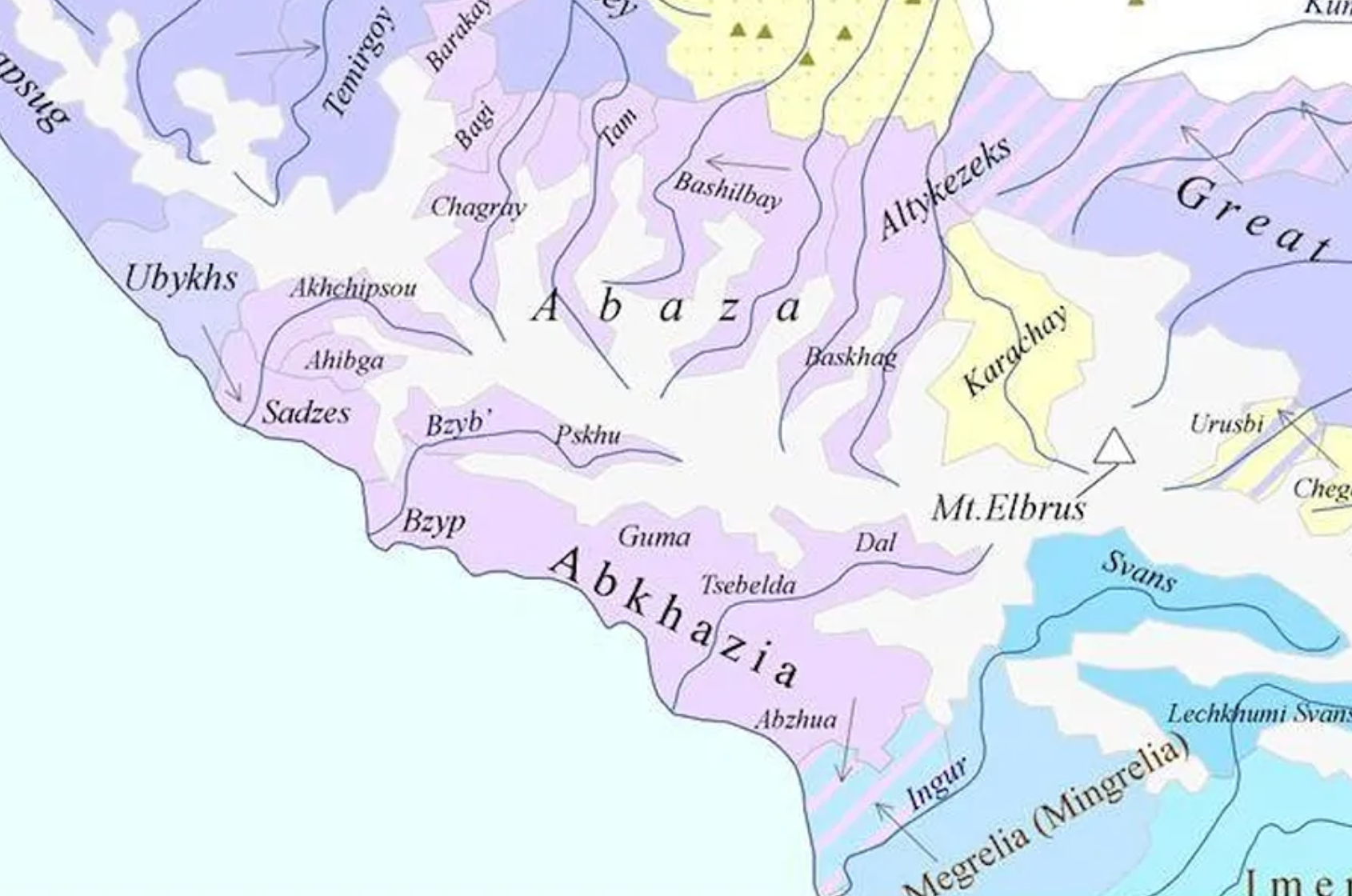

The Samurzakano region of Abkhazia, sometimes also referred to as Myrzakan, is located in the southeast of the country. Its administrative centre is the city of Gal. In the 17th century, the region was captured by the Abkhazian ruling dynasty of the Chachbas, or Shervashidzes, from the Principality of Mingrelia (Megrelia). As a result, the border of Abkhazia was established along the Ingur River. Subsequently, the territory between the Galidzga and Ingur rivers was named Samurzakano or Myrzakan after its ruler Myrzakan Chachba. The spelling “Samurzakano” is a borrowing by the Russians of the name given to the region by the Mingrelias (Megrelians), who were the previous inhabitants.

"In 1705 three brothers of the Abkhazian ruling family, surnamed Chachba (in Georgian Shervashidze) divided up their territory, one taking the north (from Gagra to the R. Kodor), the second the central Abzhywa region (from the Kodor to the R. Ghalidzga — N.B. in Abkhaz A-bzhy-wa means ‘the-between-people’), and the third, Murzakan, the southern part (from the Ghalidzga to the R. Ingur), and so this province, which was roughly equivalent to the modern Gal District, became known as Samurzakano."

— Georgian Soviet Encyclopaedia vol.9 p.37.

In 1805, the ruler of Samurzakano, Mehmed-bey, died and was succeeded by Manuchar Chachba. Manuchar Chachba was married to Ketevan, the sister of the ruler of the Principality of Mingrelia, Levan Dadiani. Using his relationship with his wife's family, and taking advantage of political turmoil in Abkhazia, Manuchar was able to negotiate for Samurzakano's incorporation into the Russian Empire. This meant that Samurzakano became part of the Russian Empire five years before the rest of Abkhazia. However, some members of the ruling family in Samurzakano, including Manuchar's brother Bezhan, did not agree with this decision.

When the ruler of Abkhazia, Kelesh-bey, died in 1808 and was succeeded by his son Saferbey, attempts were made to regain control of Samurzakano. After Manuchar Chachba was killed in 1813, the ruler of Mingrelia, Levan Dadiani, took control of Samurzakano on behalf of Manuchar's under-age son, Alexander. In 1832, General Rosen annexed Samurzakano to Mingrelia, using the justification that the ruler of Mingrelia, Levan Dadiani, had claimed that the territory originally belonged to his ancestors.

Although maps of the time show conflicting information about whether Samurzakano was part of Abkhazia or Mingrelia during this period, many contemporary writers stated that it belonged to Abkhazia. The Swiss traveller Frederic Dubois de Montpéreux, for example, writing between 1831 and 1834, states that the Galidzga river “forms the border of Abkhazia on the side of Samurzakano”, while his map shows Myrzakan as part of Abkhazia. (Gopia 2022.)

Georgica (Journal of Georgian and Caucasian Studies) Vol. 1 October 1936. (p.54). 'Ethnographical and Historical Division of Georgia' By A[ndrei] Gugushvili

+ On the Political and Ethnic History of Myrzakan (Samurzakano) in the 19th Century, By Denis Gopia

+ Scholarly-literary section: A sketch of Mingrelia, Samurzakan, and Abkhazia, by Dmitry Bakradze (1860)

+ Samurzakanians or Murzakanians by Simon Basaria

However, the people of Samurzakano were unhappy with being ruled by the Dadianis and many uprisings occurred. The Abkhazian prince Achba also fought with Levan Dadiani for control of the territory. This unrest led to Russian troops invading Samurzakano in 1834 under the command of General Akhlestyshev. The Russians built fortifications near the village of Elyr and subdued the population. Nevertheless, even after this, the population continued to resist Dadiani rule.

In 1840, Tsar Nicholas I granted Samurzakano its own banner to reward them for fighting alongside the Russians against the Dals, another group of Abkhaz. This act was described by Simon Basaria in 1990 as shameful for both the Russians and for the Samurzakanians who took up arms against their own people. Nevertheless, at this time Samurzakano was still considered by many to be part of Abkhazia. Samurzakano was returned to the structure of Abkhazia in 1855 by Tsar Alexander II.

"In the political sense, the Mingrelians are just as Russian as the Muscovites, and in the same direction they can influence every tribe in contact with them, a striking proof of which is the fact, recognised by our opponent, that due to the influence of the Mingrelians, the Samurzakanians are a branch of the Abkhazian tribe, – being in constant communication with the Mingrelians, they became completely Russian subjects and during the repeated uprisings of their fellow tribesmen did their best to help the government in suppressing disturbances and pacifying the rebels."

― Jakob Gogebashvili ('Who should be settled in Abkhazia?', Tiflisky Vestnik, 1877)

Following the end of the Russo-Caucasian war in 1864, the Abkhazian principality was abolished. Control of Abkhazia was given to the Kutaisi governor-general and the territory was renamed the Sukhum Military Department. This new department was divided into three districts (Bzyp, Sukhum, and Abzhui) and two administrations, one of which was Samurzakano. In 1888, by decree of the Russian emperor, the Sukhum Military Department, including Samurzakano, was renamed the Sukhum District within the Kutaisi Governorate.

Ethnic History of Samurzakano

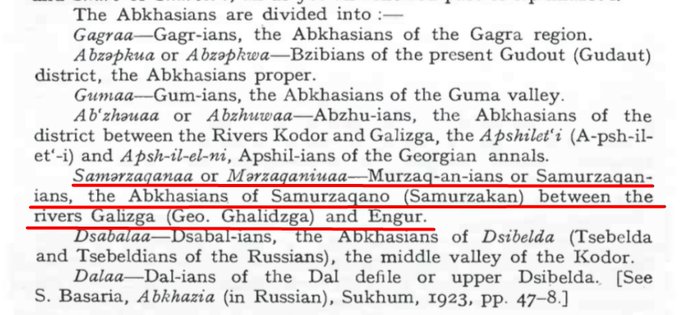

There is debate in the historical literature about the ethnic composition of Samurzakano, and how the region should be classified. As a borderland between Abkhazia and Mingrelia, it had a mixed population. The Abkhazian view is that the majority of the population in Samurzakano were Abkhaz.

In support of this view, several 19th-century sources can be cited, including the work of the Russian S. Solovyev, who states that the territory of Samurzakano had originally been populated by Mingrelians. However, he goes on to say that in the 17th century, following the capture of the territory by the Abkhazian feudal lords from the Chachba (Shervashidze) clan, the population fled. Subsequently, the territory was resettled by Kvap Chachba (Shervashidze) along with his retinue of princes, noblemen, and their families. The sparse local population that remained willingly submitted to the newcomers. According to Solovyev, most 19th-century sources classified the Samurzakanians as Abkhaz. However, he does acknowledge that there was significant migration from neighbouring parts of Western Georgia, primarily Mingrelia, during this period.

'Transcaucasian Boundaries', by John Wright, Richard Schofield, Suzanne Goldenberg (2003).

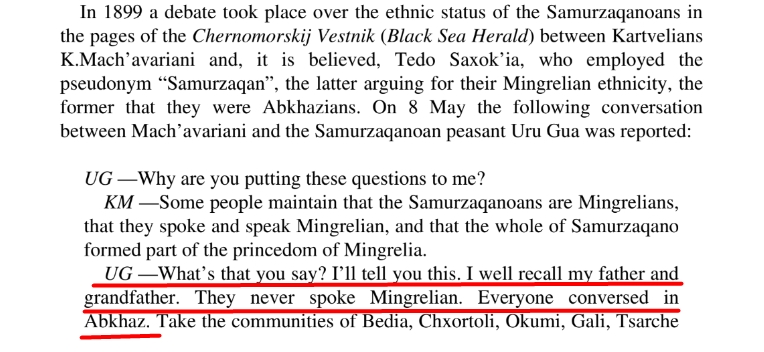

The Abkhazian researcher Teymuraz Achugba also argues for the Abkhazian identity of the Samurzakanians. He bases his argument on numerous sources from the 19th century, such as Bronevsky, Asha, Gamba, Montpéreux, Tornau, Berge, Philipson, Machavariani, Bartholomew, Albov, and many others.] He also points out that even the Georgian press of the time wrote about the Abkhaz ethnicity of the Samurzakanians.

The Russian writer P.D. Kraevich wrote in 1870 that, despite some tribal differences, the social structure of Samurzakano did not differ significantly from other parts of Abkhazia. The Russian traveller and researcher N.M. Albov, who spent five years in Abkhazia in the 1890s, wrote that the territory of Abkhazia stretched from the Gagra Ridge to the Ingur River and that in all parts of Abkhazia, it was practically only Abkhazians who lived there. Speaking specifically about Samurzakano, he stated that it was "inhabited by Samurzakanians – a tribe of Abkhazian origin with a significant admixture of the Mingrelian element".

Linguistic data from the region also shows a mixed picture. In 1877, N.K. Zeydlicz noted that Samurzakano was inhabited by both Abkhazians and Mingrelians. The French archaeologist and anthropologist Ernest Chantre conducted research in the Caucasus in the 1870s, and, based on his work, as well as the work of Zeydlicz and Eskert, an ethnic map of the Caucasus was created, which shows the linguistic contact in Myrzakan between Mingrelians and Abkhazians.

"The Abkhazians proper (the Apswa) inhabited the first three regions: the population of Samurzakan, although undoubtedly belonging to the same tribe, was influenced by proximity to, and kinship-ties with, the population of Mingrelia in its language and customs to such an extent that it formed, so to say, a separate tribe."

― The Newspaper "Kavkaz" 1877 - No 222

The Georgian philologist A.A. Tsagareli wrote in 1877 about the clash between the Mingrelian and Abkhazian languages in Samurzakano. He stated that, while the residents considered Mingrelian their native language, the men also spoke Abkhaz. Tsagareli also provides lists of both Abkhaz-speaking and Mingrelian-speaking villages in Samurzakano, indicating that there was a significant amount of bilingualism in the region.

Despite the mixing of the population, Albov states that, in the communities of Sabierio, Dikhazurga, Chuburkhindzhi, etc., which are located in the southeast of Samurzakano, the dominant language was exclusively Mingrelian. He notes, however, that “elders told me that in the old days they spoke more Abkhaz here”. He also points out that the names of mountains and rivers in the region are “almost exclusively Abkhaz”.

Statistical data about the population of Samurzakano also provides support for the idea that the Abkhaz element was predominant. The German researcher Daniel Müller, writing in 2013, discusses data from the “Family Lists” of 1886, which show that 30,640 people were classified as Abkhaz and 28,323 as Samurzakanian in the Kutaisi Governorate. He argues that, because the Samurzakanians are not listed separately in the summary tables and because the number of Abkhaz in the Kutaisi Governorate is given as 60,432, the authorities must have been counting the Samurzakanians as Abkhaz. This is further supported by the fact that the authorities had no difficulty separating Mingrelians from Samurzakanians in the data, whereas they struggled to distinguish between Abkhazians and Samurzakanians.

Similarly, in both Samurzakano and other regions of Abkhazia, Abkhaz surnames were modified[3].

Examples include:

- Abuhba→ Abuhbaya

- Ayüdzba→ Avitsbaya

- Agrba→ Agirbaya

- Adzınba→ Adzghnbaya

- Akshba→ Akishbaya

- Amichba→ Amishbaya

- Andarbua→ Andariva

- Achba→ Anchabadze, Anchibaya

- Ardzınba→ Ardzinbaya

- Arshba→ Arshbaya

- Artba→ Ardbelava

- Akhba→ Akhbaya

- Baghba→ Baghbaya

- Butba→ Butbaya

- Guadzba→ Gvadzbaya

- Gitsba→ Gitsbaya

- Dzadzaba→ Dzadzbaya

- Delba→ Dalbya or Dolbaya

- Zukhba→ Zukhbaya

- Ezugba→ Ezugbaya

- Eshba→ Eshbaya

- Jvüanba→ Zvanbaya

- Iwanba→ Iwanbaya

- İnalipa→ İnalishvili or Inaliskua

- Kuafüba→ Kavshbaya

- Kakubaa→ Kakubava

- Kapba→ Kapbaya

- Karba→ Karbaya

- Kiachba→ Kachibava

- Ketsba→ Ketsbaya

- Kiılba→ Kiılbaya

- Kırtba→ Kırtbaya

- Kalghiba→ Kolbaya

- Kvadzba→ Kvadzba

- Kukba→ Kukbaya

- Lakrba→ Lakerbaia

- Mkanba→ Mkanbaya

- Mkialba→ Mkialbaya

- Tarba→ Tarbaya

- Tıvüba→ Tıvübaya

- Khahübiya→ Khakhubaya

- Khashba→ Khashbaya

- Khintba→ Khintbaya

- Tsanba→ Tsanbaya

- Tsaragba→ Tsaragbaya

- Tsitsba→ Tsisbaya

- Tsıfüba→ Tsıshbaya

- Chachba→ Chachibaya, Sharashiya, Shervshidze

- Shakrıl→ Shakerbay, Shariya

- Shamba→ Shambaya

- Shfükhatzaa→ Shkvatzabaya[4]

- Aiba→ Aibava

- Leiba→ Leybasdze

- Muba→ Mukbaya or Mukubava

- Gumba→ Gumbadze

- Gunba→ Gunbaya

- Gubaz→ Gunbazi

- Dbar→ Dibari

- Ardba→ Ardiya or Ardbelava

- Ratsba→ Ratsbaya

- Chugba→ Chukurbaya

Prof. Kupraa emphasises that the Georgianisation or Mingrelianisation of Abkhaz surnames was a crucial component of the broader assimilation process. While linguistic assimilation and the subsequent loss of ethnic identity occurred as part of a prolonged and complex assimilation process, the transformation of surnames played a particularly significant role due to its formalisation in official population records.[5]

In both Samurzakano and other areas of Abkhazia, Abkhaz surnames were not merely adapted into Mingrelian or Georgian forms but, in some cases, were so thoroughly altered as to become unrecognisable or were entirely replaced by different surnames. Some surnames underwent gradual changes, while others were immediately altered. To illustrate, let us examine archival material documenting the evolution of the Ankuab surname into Mikvabia: in 1868, the surname appeared as Ankuab in the Ochamchira region, as Ankanbai in 1873, as Amkvabia in 1903, and as Mikvabia by 1915.[6]

In some cases, surnames were changed without any “evolutionary” process. For example:

- Braskiıl→ Buliskeria

- Shakrıl→ Shakrilbai, Shakirbai, Shakaya, or Sharia

- Chaabalurhua→ Sotikua or Sotishvili

- Inal-ipa→ İnaliskua or Inalishvili

- Alkhorba→ Mertskhulava

- Tsimtsba→ Sirgenava

- Chanba→ Esava

The Initiators and Creators of Surname Changes

It is noteworthy that the initiators and inventors of surname changes were predominantly Georgian, more specifically Mingrelian, clergy members. They often altered the surnames of newborns during baptism. Naturally, parents and children who did not speak Georgian or understand the Georgian script became aware of these deceptions by Georgian priests much later, typically after the establishment of Soviet power, when church records were almost the sole written source of documentation.

+ Georgian Myths vs. Historical Facts: The Reality of Abkhazian History

+ Responses to Some Fanciful Ideas of a “Historian” from Paris, Badri Gogia, by Denis Gopia

+ Rewriting History? A Critique of Modern Georgian Historiography on Abkhazia

+ The value of the past: myths, identity and politics in Transcaucasia, by Victor A. Shnirelman

The Role of the Church

In 1918, during the short period of Menshevik rule in Georgia, many Abkhaz were forced to change their surnames. Oleg Lakrba, for example, whose family name is over a thousand years old, describes how his ancestors were forced to change their surname to Lakerbaya by church workers, the majority of whom were Mensheviks. Tengiz Inal-ipa recounts a similar story, describing how his great-grandfather was forced to change his name from Inal-ipa to Inalishvili during the revolutionary years. He recalls that those who resisted were often killed.

The Georgian public figure Konstantin Machavariani wrote in 1900 in the Black Sea Bulletin about the activities of Georgian "culture carriers" who sought to reshape Abkhaz surnames by adding Georgian endings to them. He criticises these individuals, describing them as "vigilant agents of economic conquest" who imposed their own language on the Abkhaz. Machavariani reserves his strongest criticism for the Georgian and Mingrelian priests who undertook this "Georgianisation of Abkhaz surnames". He points out that this alteration was often done “with almost complete indifference from the bearers of these names” who, on account of their illiteracy or naivety, did not realise what was being done.

Efforts by the small number of Abkhaz clergy to correct these distorted surnames are also evident in church records. Between 1871 and 1882, a priest named Nikoloz Sacaya served in the village of Gup. During his tenure, he recorded names in Georgian and, as a rule, appended the suffix “ia-aia” to all Abkhaz surnames ending in “ba.” At times, not only were suffixes added, but the roots of the surnames were also altered. For instance, the surname Kabba (more accurately Kapba) became Kabbaia, Hintuba became Hintubaia, Zykhuba became Zokhubaia, Ashuba became Ashibaia, and Adleiba became Adlibaya.[7]

In October 1882, an Abkhaz priest named Petr Pilia was appointed to serve the same village. During his six years of service, it appears that Petr Pilia recorded Abkhaz surnames in church registers documenting baptisms, marriages, and deaths without distortion. Examples include Zikhuba, Buliskirba, Khintba, Jinjalba, Bganba, Atarba, Kabba, Shamba, Amchba, Nanba, and Hajimba.[8]

However, with the appointment of a new priest of Georgian origin, P. Pareishvili, the distortion of Abkhaz surnames, resumed. Similar cases were observed in other regions of Abkhazia. For instance, Aleksandr Ajiba, an Abkhaz priest from the village of Mgudzirkhua, corrected revised surnames such as Tarba, Jiba, and Ajiba in birth registers from 1906 and 1907. Similarly, Basil Agrba, who served as a priest in the same village between 1909 and 1916, recorded surnames like Leiba, Mukba, Agırba, and Ajiba without any alterations.[9]

The Alteration of Abkhaz Names

Georgian clergy members not only changed Abkhaz surnames but also altered their given names. Historical records document cases where individuals ended up with dual names: their original Abkhaz name and a new Christian (Georgian) name. Examples include Mysirk becoming Mose, Gıd becoming Grigory, Albak becoming Anton, Gedlach becoming Gabrieli, Kishu becoming Kirile, Sida becoming Salome, and Hanaüf becoming Febrone.[10]

These arbitrary actions became so excessive that even some Georgian leaders opposed them. For instance, K.D. Machavariani criticised Georgian priests, referring to them as “Kulturträger,” thus expressing justified outrage at the actions of Georgian clergy in Abkhazia.[11]

The prominent Georgian educator and opinion leader Y.S. Gogebashvili, despite being a fervent advocate for settling Mingrelians in depopulated Abkhaz lands, wrote in 1907 on behalf of the "Sukhum Georgian Lovers" about the unacceptability of "distorting and altering Abkhaz surnames."[12]

In 1912, Dirmit Gulia, one of the seminal figures of Abkhaz literature, expressed his indignation as follows:

“Since the establishment of Russian rule, that is, since 1810, priests who neither knew a single word of the local or state languages nor were even literate in their own language have been appointed here. These priests merely occupied these positions to collect salaries and devoted themselves to translating Abkhaz surnames and village names into Georgian. For example, Maan became Margania, Achba became Anchabadze, Inal-ipa became Inalishvili, and Shat-ipa became Sotishvili.”[13]

In Samurzakano, the idea that all Abkhazians bearing Mingrelian or Mingrelianised surnames were of Georgian origin was actively propagated among both the Abkhaz and Mingrelian populations. Naturally, the continuous dissemination of such notions suppressed the national identity of the Abkhaz living in the region and eventually led to its erosion. As is well known, a key element in the structure of ethnic self-awareness is the definition of national identity, which involves the community recognising its unique characteristics and maintaining a holistic perspective on its historical past, both socially and individually.[14]

For the Abkhaz, one of the foremost markers of their collective identity has always been their “own” Abkhaz surnames and their deeply rooted family heritage.¹⁵ This is universally regarded by the majority of the population as an integral and unique aspect of the Abkhaz people. Consequently, the alteration or renaming of surnames was a violent act that cast doubt on the national origins of individuals and the Abkhaz as a whole. By the end of this process, those who began to question their ethnic origins, especially the younger generation, became easy targets for assimilation policies.

Due to these systematic practices and the notorious church records, many Abkhaz surnames remain officially recorded in their distorted forms, such as Abukhbaya, Agrbaya, Adzinbaya, Akishbaya, Anchabadze, Arshbaya, Argunia, Bagbaya, Butbaya, Gvazbaya, Zvanbaya, Zukhbaya, Inalishvili, Ketsbaya, Kırtbaya, Kolbaya, Kakubava, Lakirbaya, Ezukhbaya, Eshbaya, and others. These altered versions were transcribed into Georgian and, later, into Russian, which further perpetuated these distortions. This remains a serious issue to this day.

Lasting Effects

For example, when examining an Abkhaz passport, the surname written in the Abkhaz section often differs from the Russian section. For instance, a surname might appear as Kutsniya in Abkhaz but as Kvitsiniya in Russian. Other examples include:

- Biguaa → Bigvava

- Lagulaa → Lagvilava

- Arstaa → Aristava

- Agumaa → Agumava

- Akırtaa → Akirtava

- Shanaa → Shanava

- Horaa → Horava

- Guazaa → Gvazava

- Eymkhaa → Emukhvari

Contemporary Provocations and False Claims

Today, those who seek to provoke this issue attempt to build their arguments on the false claim that Abkhaz surnames are Georgian. They publish distorted lists, asserting that the majority of families constituting the Abkhaz people are of Georgian or Mingrelian origin, and therefore alleging that Abkhazia is, in fact, Georgian territory(!).

Of course, such cultural exchanges and intermingling are natural among neighbouring communities who have lived under shared states for hundreds or thousands of years. The integration of Georgian, Mingrelian, Turkish, Russian, and other surnames into Abkhaz society can be demonstrated easily and definitively through straightforward studies, leaving no room for controversy. However, ignoring these realities, continuing assimilationist policies, and deliberately distorting facts to build a societal narrative on falsehood is, at the very least, a futile effort destined to fail.

The solution to the confusion inherited from the practices of church priests and the Stalin-Beria era is, in our view, remarkably simple. The government of Abkhazia could, in the light of scientific evidence, enact a legal regulation mandating the correct spelling of surnames in population registries and passport offices. During identity renewal processes, all inaccuracies could be corrected in one sweep. However, since Abkhazia is not yet recognised by the international community, the overwhelming majority of its people must rely on Russian passports. Any changes made to local records would necessitate subsequent corrections in Russian passports—a process involving lengthy procedures. This unfortunately makes achieving tangible results in the short term exceedingly challenging.

Sources:

- Kupraa, A. Dzhiget Surnames in Georgia. “Dzhiget Compilations,” no. 1, The Ethno-Cultural History Problems of Western Abkhazia and Dzhigetia (Вопросы этнокультурной истории Западной Абхазии или Джигетии). Moscow, 2012, p. 160.

- Achugba, T.A. Ethnic History of Abkhazians in the 19th–20th Centuries: Ethnopolitical and Migration Perspectives. Sukhum, 2010, p. 182.

- Kupraa, A.E. Problems of Traditional Abkhaz Culture. Sukhum, 2008, pp. 81–101.

- Inal-ipa, Sh.D. Anthroponymy of the Abkhazians. Maikop, 2002, pp. 259–262.

- Kupraa, A.E. Ibid., p. 81.

- Abkhazia State Archive. Fund 57 (Ф.57), Inventory 1 (оп.1), Case 5 (д.5), Page 106 (л.106); ADAM. Fund 1 (Ф.1), Inventory 1 (оп.1), Case 348 (д.348), Page 47 (л.47); ADAM. Fund 57 (Ф.57), Inventory 2 (оп.2), Case 489 (д.489), Pages 3–4 (лл.3–4); ADAM. Fund 57 (Ф.57), Inventory 2 (оп.2), Case 495 (д.495), Page 2 (л.2).

- Abkhazia State Archive. Fund 1 (Ф.1), Inventory 1 (оп.1), Case 351 (д.351), Pages 2, 4–6, 24, 27 (лл.2, 4–6, 24, 27).

- Abkhazia State Archive. Fund 1 (Ф.1), Inventory 1 (оп.1), Case 519 (д.519), Pages 12, 14, 17–18, 20 (лл.12, 14, 17–18, 20).

- Abkhazia Republic Population Registry Archive. Fund 2 (F.2), Metric Books, Mgudzırkhua Village: 1907, no. 11440, Page 2 (L.2); 1911, no. 24910, Page 4 (L.4); 1912, no. 6004, Page 8 (L.8), and others.

- Abkhazia State Archive. Fund 1 (Ф.1), Inventory 1 (оп.1), Case 516 (д.516), Pages 8–10 (лл.8–10).

- Machavariani, K.D. “The Property Issue in Abkhazia.” Black Sea Bulletin Newspaper, 1900, no. 121, 124.

- Gogebashvili, Y.S. Selected Essays, vol. IV. Tbilisi, 1955, p. 215 (in Georgian).

- Gulia, D.Y. “What Does Abkhazia Need?” Transcaucasian Joint Working Mission, 1912, no. 10, p. 152; Dimitri Gulia, Essays. Eds. Kh.S. Bgajvüba, S.L. Zukhba. Sukhum, 2003, p. 350.

- Bromley, Y.V. Essays on Ethnos Theory. Moscow, 1983, p. 176.

- For Abkhaz anthroponymy, see: Marr, N.Y. “On Abkhaz Personal Names” in On the Abkhaz Language and History. Moscow–Leningrad, 1938, pp. 92–94; Ibid., “On the Origin of the Name Anan” in On the Abkhaz Language and History, pp. 95–97; Inal-ipa, Sh.D. The Abkhazians. Sukhum, 1965, pp. 403–413; Anthroponymy of the Abkhazians. Maikop, 2002; Tsulaya, G.V. “On Abkhaz Anthroponymy” in Ethnography of Names. Moscow, 1971, pp. 70–76; Ibid., “On Georgian-Abkhaz Anthroponymy” in EO, no. –, Moscow, 1999, pp. 125–136; Bgajvüba, Kh.S. “On Abkhaz Personal Names” in Proceedings II. Sukhum, 1988, pp. 195–205; Achugba, T.A. Abkhaz Settlements in Achara. Batumi, 1988, pp. 34–39 (in Georgian; with Russian summary); Ibid., “Half of Abkhazia” in Aydgylara Newspaper, 6 October 1989 (in Abkhaz); Tkhaitsukhov, M. “Abaza Surnames as a Historical and Ethnographic Source” in Izvestiya ABIYALI, XV. Tbilisi, 1989, pp. 105–119; “Abkhazians Living in Turkey,” Tsvizhba, Ts., Apsny Kapsh Newspaper, 7 April 1990 (in Abkhaz); Guajvüba, R.Kh. “The 1867 Deportation of Abkhazians from Dal and Tsabal” in Apsny Kapsh Newspaper, 31 May, 1 June, 21 June 1990 (in Abkhaz); Kupraa, A.E. “Abkhaz Surnames in the Gal Region: What Happened to Them?” in Apsny Newspaper, 9 December 1998 (in Abkhaz); Ibid., “Surnames of Samurzakano: History and Modernity” in Echo of Abkhazia Newspaper, 23 and 30 January 2000; Ibid., “On the Transformation History of Abkhaz Family Names (Based on Samurzakano in the 19th–20th Centuries)” in Caucasus: History, Culture, Traditions, Languages. International Scientific Conference, 28–31 May 2001. Sukhum, pp. 30–39; Ibid., From the History of Abkhaz Anthroponymy; Smır, G.V. Basic Features of Abkhaz Surnames. Sukhum, 2000; Maan, O.V. “From the History of Abkhaz Family Names” in Abkhazology: History, Archaeology, Ethnology. Issue II. Sukhum, 2003, pp. 189–198; Dasania, D.M. “On the Research History of Abkhaz Surnames (up to 1961)” in Abkhazology: History, Archaeology, Ethnology. Issue II. Sukhum, 2003, pp. 199–209.