Scholarly-literary section: A sketch of Mingrelia, Samurzakan, and Abkhazia, by Dmitry Bakradze (1860)

Dimitri Bakradze (1826–1890), Georgian scholar of history, archaeology, and ethnography.

This article, written by the Georgian historian Dmitry Bakradze (1826–1890), was originally published in Gazeta Kavkaz in 1860 across two issues (No. 48 pp. 293-294 and No. 49 pp. 298-299). It offers an exploration of the geographical, historical, and cultural aspects of Mingrelia, Samurzakan, and Abkhazia. Bakradze vividly describes the natural landscapes, including rivers, forests, and mountain ranges, and traces the historical evolution of these regions, from ancient Greek colonies to his time in the 1860s. He also analyses into the customs, lifestyle, and socio-political state of the local populations.

This English translation, provided by AbkhazWorld, aims to bring this rich historical account to a broader audience, offering a valuable perspective on the intertwined histories of the region.

Scholarly-literary section

A sketch of Mingrelia, Samurzakan, and Abkhazia

Knowledgeable individuals would likely agree with me that the most remarkable regions in the Caucasus and Transcaucasia are found in Western Georgia, particularly in the areas historically known as Colchis, later as Lazica, and subsequently comprising Imereti, Guria, Mingrelia, Samurzakan, and Abkhazia, though it should be noted that the latter two were not originally part of these territories. One cannot fully grasp their essence without seeing them with one’s own eyes. Here, within a relatively small area, nature displays a diverse and majestic character; there is an extraordinary abundance of rivers and streams; the local population, their languages, and their way of life are clearly demarcated by river basins. Additionally, this region is replete with architectural monuments from ancient times, bearing traces of the influence of the Hellenes and Romans, Byzantines, and the Abkhaz-Georgian Bagrationi dynasty.

For a long time, I had wished to see these places and verify my geographical and historical notes on the Kutaisi Governorship firsthand. An opportunity arose when His Excellency, General-Governor Prince G. R. Eristov was scheduled to inspect the territory under his command last April; I was part of his entourage. Spring is the best time for travel along the coastal regions: the heat is moderate, the vegetation has already flourished, and the rains are brief, with river overflows not causing prolonged delays.

We set out on the 9th and headed towards Martvili and Jvari, then to Okumi, Bedia, and Mokvi, followed by Sukhum and Gagra. My return journey took me through Zugdidi, Tsaishi, Khopi, and Nakalakhevi. Thus, I managed to visit nearly all the notable places in Mingrelia, Samurzakan, and Abkhazia, witnessing the rapid development of the plant kingdom and attempting to observe the lifestyle of the locals.

The general character of the region I visited is such that it leaves a lasting impression even on the most superficial observer. The high, rugged spur of the main Caucasus Range, extending from the southeast to the northwest, sends out significant branches, which gently descend towards the Black Sea, forming elevated basins and valleys in some areas, and rocky shores and shaded ravines in others. Some of these branches protrude into the sea as picturesque capes, creating bays. Almost all the major offshoots run parallel to the coast, rising in tiers above one another; the highest of these remain covered in snow, at elevations between 10,000 and 13,000 feet, revealing patches of primordial rock, including porphyry, granite, and limestone. Their view from the sea is particularly splendid: they take on varied and whimsical shapes. The gorges, through which the rivers flow, open up their dark passages, winding further until they disappear into the mountain masses; the valleys stretch out over considerable distances, taking on hilly or undulating forms; closer to the sea, they become flatter and more expansive.

The characteristic features of these mountains and valleys are quite unlike those observed elsewhere in the Caucasus: their lines are not harsh—on the contrary, they are gentle and delicate; their colours shift between light blue and dark blue hues, owing to the extraordinary abundance of vapours rising from the sea and the forests, forming light misty clouds that swirl in the air on clear days. This appearance persists almost throughout the year. The masses of snow and glaciers on the highest peaks give rise to a vast number of streams and rivers, among which, after the Rioni, the most significant are the Ingur, Kodor, Tskhenis-Tskali, and Bzyb. All of these were known to the ancient Greeks and Romans, retaining the same characteristics, and some even the same names. After cutting through the gorges, they rush down their narrow, stony beds with remarkable speed and noise, foaming and swirling, becoming calmer and wider only upon reaching the plains. Aside from the Rioni, only the Ingur and Kodor, and only in their lower courses, allow for navigation by small boats. These rivers swell during the hot season, with the melting of snow in the mountains, and become especially dangerous during heavy rains, which are frequent here; their clear and transparent waters turn muddy and murky; unnoticed streams transform into raging rivers, and the Ingur, Kodor, Bzyb, and Tskhenis-Tskali become, within hours, impassable, flooding vast areas, rolling along with roaring waves and uprooted century-old trees.

Bridges in the valleys do not last; only in the mountainous areas are fragile suspension bridges, made of twigs or grapevines, constructed for pedestrian use by the locals. These constantly sway, and only those accustomed to them dare to step on them, for fear of dizziness and the risk of slipping and falling into the whirlpools below. On these rivers, in the valleys, there are still, albeit infrequent, native boats, which, having an ancient design and being made from hollowed-out wood, are skilfully and boldly navigated by local rowers.

Prince G. R. Eristov, after careful consideration, ordered the construction of a route through the upper regions. This decision was based on a thorough study of the local terrain. Previously, the permanent postal route to Abkhazia ran through Zugdidi, then along the seashore, passing through Redut-Kalé and Sukhum, over largely flat but clayey and sandy areas that, during the rainy season, turned into a sea of swamps and bogs, necessitating extraordinary expenditure to maintain the route; the construction of bridges was nearly impossible due to the frequent and strong flooding of the rivers and shifting of their beds.

The upper regions offered a higher likelihood of success: in our opinion, this was the site of an ancient path, and remnants of bridges can still be found in places; the soil here is primarily firm and stony; there are few significant ascents and descents, which can be made unnoticeable by applying the latest methods of road construction through the mountains. Furthermore, building sturdy bridges will not require substantial expenditure, as the rivers here have narrow, rocky banks, and the necessary materials are readily available. Construction on some of these has already begun: the bridges over the Abasha and Khopi will be completed this summer; materials for the remaining ones are being prepared. Roadwork is progressing actively, involving battalions; road grading and clearing have already been undertaken in many areas, and convenient points for outposts have been identified. Thus, this route, which, even in its current state, we traversed easily and without difficulty, will pass by Martvili to Jvari, where it will branch towards Svaneti through the Ingur Gorge, descend to Okumi, and, passing by two majestic ancient monuments—Bedia and Mokvi—proceed to Sukhum, and from there through Anakopia and Souksu to the Gagra fortification—thus, it will cut through the very heart of Abkhazia.

Beyond the strategic importance of this route, in relation to our government’s approach to Abkhazia and Dzhigetia, the greatest benefit from convenient connections can only be fully appreciated by those who have repeatedly had the opportunity to travel through the wild areas of Samurzakan and Abkhazia. We deem it necessary to elaborate further on this issue.

It is well known that the vast area stretching from the Surami Pass to the far borders of Abkhazia consists almost entirely of dense forests, with the exception of certain parts of the large Rioni basin, the plains of Mingrelia, and a few other minor valleys. The further one travels from Kutaisi, the denser and more immense these forests become. Here, vegetation, which appears as grasses and shrubs in Georgia and Imereti, takes on the form of ancient, tree-like structures, while the trees themselves grow to colossal sizes. Here, the malodorous fern, which in its rapid growth reaches up to one sazhen (around 2.13 metres) in height and is found in thick, frequent patches, and alongside it, the slender-stemmed azalea, almost 2 sazhens (about 4.3 metres) high, with beautiful yellow flowers emitting a heavy, intoxicating fragrance, cover all the valleys and glades of Samurzakan and Abkhazia. The ringed rhododendron, a jewel of the Black Sea coastline, with long, graceful leaves and lush purple bouquets, forms thickets along the slopes and ravines, reaching up to 3 sazhens (approximately 6.4 metres).

Above all of this, ancient trees spread their dark green foliage like canopies. These trees grow in clusters, with different species appearing in alternating stretches, many of which reach heights of 25–30 sazhens (around 53–64 metres) and circumferences of about 2 sazhens (approximately 4.3 metres). These include plane trees, beeches, hazel, alders, chestnuts, and many others. The palm tree appears only in the mountain gorges, where it grows in extraordinary abundance and is a subject of trade with merchants from Trebizond and Constantinople, providing, as I have heard, an income of 7,000–8,000 silver roubles per year to a single landowner in Abkhazia.

All these forests are entwined with impenetrable masses of foreign climbing plants and grapevines. The trunks of these vines, in their reaches, grow to about 1.5 arshins (a little over 1 metre) in circumference. Twisting in the air, they climb up the trees, entwining their trunks, and stretch from one to another, descending with numerous branches that sway in the emptiness. Their true home is Abkhazia, from Pitsunda to Ochamchira, where a single tree can sometimes yield up to 30 poods (around 491 kilograms) of grapes.

In most of these places, there is a perpetual dampness and constant twilight; the tranquillity of nature is interrupted by the sound of water and the singing of birds, occasionally accompanied by the bleating of goats and the presence of small grazing cattle. The population is scarcely noticeable: scattered here and there in the thickets, only rarely do solitary wicker huts with thatched roofs and small plots of land around them come into view. The people rarely live in groups of more than 5–10 families, a characteristic that prevails throughout Mingrelia, Samurzakan, and Abkhazia.

Georgica (Journal of Georgian and Caucasian Studies) Vol. 1 October 1936. (p.54)

+ Samurzakanians or Murzakanians by Simon Basaria

+ On the Political and Ethnic History of Myrzakan (Samurzakano) in the 19th Century, By Denis Gopia

+ Who are the Mingrelians? Language, Identity and Politics in Western Georgia, by Laurence Broers

The roads here are merely rough paths, suitable only for pedestrians and barely usable for pack animals; there are very few cart tracks, and those that do exist follow the course of rivers, leading towards the sea. These paths wind through ravines, twist along slopes and elevations, sometimes appearing, sometimes vanishing. It is practically impossible to travel here with just one Cossack, without the help of a chapar-khan or local guide; only they can determine your location and the direction of your route. Wrapped in a burka (a traditional cloak) and wearing a bashlyk (a pointed hood) on their head in case of sudden rain, they quietly move ahead of you, pushing aside or cutting the branches of prickly shrubs swaying in the air, skirting around swamps and enormous, often decaying stumps, which have fallen either due to stormy winds or because of the locals' unfortunate habit of setting them on fire, lighting bonfires at their roots during the night or in cold weather. Where your path passes by settlements, the chapar-khan and Cossack often have to stop to dismantle fences erected across the roads.

If there has been a heavy downpour, even for just two hours, the rivers will have swelled up, and you will have to either wait or, without the necessary experience, dare not attempt to ford them: the muddy waves surge against one another, and large boulders roll with a roar. For crossing larger rivers, you can confidently rely on a small kayuk (a type of boat), mostly made, as mentioned above, from a single hollowed-out log and about three sazhens (6.4 metres) long. It appears as though it might capsize at any moment, and your life seems to hang by a thread; you tremble, and your vision blurs, but do not be afraid: this is a minimal danger. The half-naked rowers, who look at you with a sense of triumph, barely manage to push off the kayuk before you find yourself on the opposite shore; the horses are led across by swimming.

In the political sense, the Mingrelians are just as Russian as the Muscovites, and in the same direction they can influence every tribe in contact with them, a striking proof of which is the fact, recognised by our opponent, that due to the influence of the Mingrelians, the Samurzakanians are a branch of the Abkhazian tribe, – being in constant communication with the Mingrelians, they became completely Russian subjects and during the repeated uprisings of their fellow tribesmen did their best to help the government in suppressing disturbances and pacifying the rebels.

― Jakob Gogebashvili (Who should be settled in Abkhazia?, Tiflisky Vestnik, 1877)

During climbs and descents, and when transitioning from the midday heat to the evening dampness, which is quite pronounced here, you risk experiencing bouts of fever, especially if you are accustomed to the delicate comforts of European living. Of course, you will not be pleased with the inevitable overnight stay under the open sky, where you might imagine Samurzakan or Abkhazian savages sleeping somewhere nearby, or in a wattle-and-daub structure divided into two or three sections, where the wind freely blows from all directions, where cows sleep close by, and where hospitable hosts offer you simple ghomi (a type of porridge), sometimes with cheese, which they place in two layers using a wooden spatula on a long, four-legged bench set before a low table (takhta) where you sit. They also serve large chunks of beef and mutton, but mostly goat meat, with various sharp seasonings—all washed down with fairly tolerable wine from ox or buffalo horns of varying sizes. At the end, you are treated to the commonly consumed sour milk, into which, if you wish, and as much as you wish, you can add honey.

In the middle of the night, you may find yourself pleasantly lulled to sleep by the sharp, melodious clicking and trills of nightingales, or unpleasantly disturbed by the wild and plaintive howls of jackals, somewhat reminiscent of a child’s cry, repeated in chorus from different directions—these silent dwellers of the entire region are a true scourge for the poor locals.

If there is even a spark of poetry within your soul, nature will more than compensate you for the hardships and inconveniences you endure. Look around you: the views are stunningly beautiful and diverse! Above you, the austere, snow-covered ridge rises into the sky, fractured by gorges and crevices through which mountain torrents rush; below you, deep basins and valleys appear as if freshly formed, with fenced fields of ghomi or maize and natural vineyards; a vast, undulating plain stretches out, partially cleared of its forest cover, where silver streams weave their way like whimsical threads, while farther on the horizon, the light blue line of the sea is clearly visible, dotted with the black silhouettes of steamers and boats with sails and barges, shimmering and sparkling, or churning and crashing loudly against the shore. And finally, before your astonished eyes, silent witnesses of prehistoric and historical times suddenly rise—towers and castles, walls and palaces, temples and monasteries, all uniquely and picturesquely entwined with ivy over their roofs and walls, overgrown with a veritable forest, standing tall on the heights and slopes of mountains, in valleys and ravines.

Gazeta Kavkaz (No:48), 1860 pp. 293-294.

******

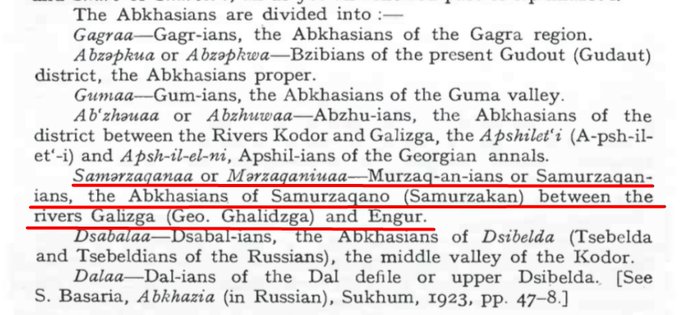

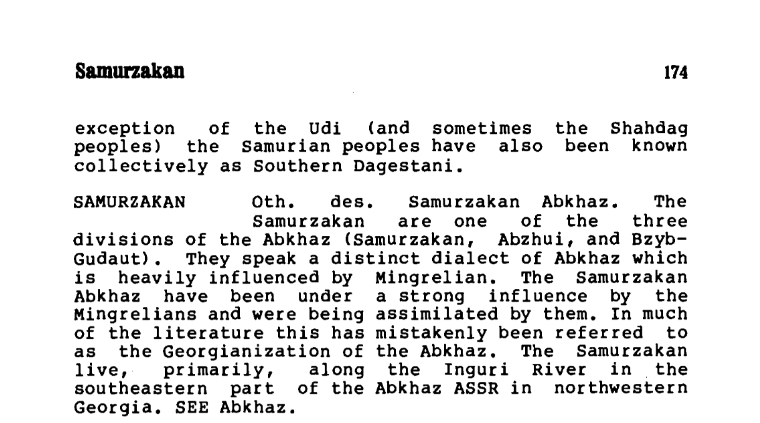

Who erected these monuments, and to which eras do they belong? This is the question that naturally arises in the mind of any traveller… Their fate is closely intertwined with the fate of the region, yet its early history is as mythical as the early history of almost any people. What is known for certain is that Mingrelians and Abkhazians are distinct tribes; we do not speak of the Samurzakanians, for, according to some, they are an Abkhazian tribe, while, in our opinion, they represent a mix of Abkhazians and Mingrelians. More or less reliable information about them has been passed down to us by ancient writers of Europe and Asia. They point out their origins and places of residence, describe their rivers and cities, their way of life and customs, their relations with one another, and their encounters with other peoples.

According to their accounts, most of the inhabitants of the Caucasus were formed as a result of various migrations that occurred at different times, and the Abkhazians trace their origins to an Egyptian colony that Sesostris the Great established on the shores of the Pontus Euxinus (Black Sea) in the 12th century BCE. As evidence of this, some modern authors point to the resemblance between Abkhazian features and the facial characteristics preserved on Egyptian mummies, the presence of Coptic vocabulary retained in their language, common customs in the life of both peoples, and even certain ancient Colchian coins. The Abkhazian language is unique. Some scholars trace it back to the same root as the Circassian language, but the renowned Pallas and Mr. Ljul’e, who studied them on-site, argue that this similarity is the result of the longstanding proximity of Circassians and Abkhazians. Our philological knowledge is only certain in this respect: that the same language is spoken by the Dzhigets, Tsebelda people, Medozgoj (or Medovyevtsy, subdivided into Akhchemtzy, Souksy, and Aibga), and the Abazinians, who share a similar way of life, indicating a common origin.

Peoples of the USSR An Ethnographic Handbook By Ronald Wixman (2017).

The very name ‘Abkhazian’ is quite ancient: to the Greeks, they were known as Avags… Mingrelians are a Kartvelian tribe, speaking a corrupted Georgian dialect, entirely shared with the dialect of another Georgian tribe, the Laz, who live around Trebizond and have, from ancient times, had as their neighbours to the northeast not the Mingrelians, but the Chokh [?Adzharian] Georgian tribes and farther the Gurians, whose language, however, they do not understand—an unresolved circumstance, despite the efforts of scholars.

The lands inhabited by Mingrelians and Abkhazians, as well as the entire eastern coast of the Black Sea, are famed for the long-lasting influence of the Greeks: the voyages of Priam [?Phrixus] and Helle after the Golden Fleece, and the expeditions of the Argonauts, are myths that point to the beginning of the settlement of these lands by Greek colonies, which later flourished and left their traces in architectural monuments and even in the rights of the Caucasus. These colonies filled the shores of the Pontus and penetrated into the interior of the region. The most well-known among them were Illyria, Heraclea, and Pitiunt, but the most important was Dioscurias, later renamed Sebastopolis; it was wealthy.

It was situated in the centre of Abkhazia, in Tskhumi, as referred to in Georgian chronicles, at the port of Sukhum, between the rivers Beslet and Madzhara, where the remnants of buildings, towers, and churches have been preserved to this day, along with the remains of a massive wall known to the ancients as the Wall of the Koraxians, derived from the words kochakh-kodort, which is why the Tsebelda people, in whose vicinity it ran, were called the Koraxians. Erected as a defence against the invasions of mountain tribes, it stretched northeast along the watershed between the Kelasuri and Madzhara rivers to the village of Gerzaul, and then eastward across the Kodor, reaching the Ghalidzga River, or, according to Diodorus, the Ingur, spanning approximately 160 versts (around 170 kilometres) in length. I saw it in three locations—at Kelasur, between the headwaters of the Dghamsh and the Kodor, and at Gerzaul. It is constructed of cobblestones and has semi-collapsed towers positioned closely to one another. The locations of other colonies are also marked by ruins.

From here, the Greeks conducted trade with Northern Asia and India. Their routes to Northern Asia followed two paths: via the Kodor Valley and along the Teberda to the Kuban, or through Bzyb to the Zelenchuk Valley and further across the steppes; the route to India initially involved travelling by ship along the Phasis (now Rioni) to the Qvirila River, on the right bank of which the remains of their trading post, Sharopan, still exist. From there, the route continued overland through the Surami Pass to Georgia and Persia. There is no doubt that the prolonged Greek presence along the shores of the Pontus was beneficial for the local inhabitants. According to Strabo, the Greeks employed 70 interpreters in Dioscurias to communicate with the Caucasian mountain tribes who gathered there for trade purposes. Through constant interaction with these civilised colonists, their disposition was bound to be softened.

"The Abkhazians proper (the Apswa) inhabited the first three regions: the population of Samurzakan, although undoubtedly belonging to the same tribe, was influenced by proximity to, and kinship-ties with, the population of Mingrelia in its language and customs to such an extent that it formed, so to say, a separate tribe."

The Greek influence, of course, had an even stronger impact on the inhabitants of the valleys, who were known by the name Colchis. From prehistoric times, they were fairly advanced and, according to the famous German geographer Karl Ritter and the scholar Dubois de Montpéreux, had been enlightened by Indian magi who founded colonies here long before the Hellenes ceased to be barbarians. From here, they spread the seeds of civilisation to Greece itself. The well-known myth of the Argonauts and the Colchian queen Circe, the Colchian city of Aia, which later became Archeopolis or Nokalakevi—thought to be described by the captivating pen of Homer in the Odyssey—lay on the right bank of the Tskhenistskali River, at the foot of the mountain Unagira, known in Georgian chronicles as Deda-Mukha in the native language. This city astonished me with the remains of its vast, massive walls, towers, and a double castle, with partially surviving chambers made of hewn stone, a long underground passage to the Tskhenistskali, and an extraordinary number of ruins in the surrounding area.

The Romans were not much involved in trade, and with their military focus, the Greek colonies declined. The Caucasian tribes became more isolated, but they were revitalised by Christianity, which took root here shortly after the Ascension of Christ, brought by the Apostles themselves: Andrew, Matthew, and Simon the Zealot, two of whom were martyred here by the Svans, with the remains of Simon being interred in Nikopsia, on the coast of Abkhazia. On the sites of ancient colonies, episcopal sees were established, the most notable being Bedia, Ilori, Mokvi, Aranda, Sebastopolis (or Okhvame), Nikopsia, Pitsunda, and Tagrinda. These were so distinguished that many of their bishops attended ecumenical councils. During this period, Abkhazia served as a place of exile for Byzantines, and it was here that the famous preacher John Chrysostom was banished. The Byzantines spread Christianity among the mountain tribes along the same routes previously used by Greek traders, specifically through the Teberda to the Kuban, as this path is still marked in places by the remnants of ancient temples.

From the 5th century CE, Lazica, encompassing the entire area from the Ingur to the mouth of the Chorokhi, became the stage of a prolonged struggle between the Byzantines and Persians. During this period, Christianity, weakened by the wars, was reinforced in Abkhazia, and a magnificent cathedral was built in Pitsunda by Justinian. The conflict ended in the 6th century with a decline in Greek influence. Over the following centuries, Abkhazia was ruled by a series of non-hereditary local rulers who were alternately subordinate to Byzantium and Georgia. From the 9th century, the Abkhazian prince Leon became hereditary; in the 10th century, the Bagrationi dynasty ascended the throne, uniting Georgia and Abkhazia. For two and a half centuries, the region known as Abkhazia extended from the Kapetistskali to the Surami Pass, and the rulers bore the title of Abkhazian-Georgian kings. Many of them were renowned and powerful, particularly Bagrat III and Bagrat IV, David the Builder, and Queen Tamar. They initially resided in Kutaisi and later in Tbilisi, extending their influence across the entire Caucasus and beyond, giving a significant boost to Georgian literature.

It was during this era that translations of the Holy Scriptures and the works of the Church Fathers, as well as translations of Greek philosophers, and national epics by Rustaveli and Chakhrukhadze, were produced. The centres of the greatest development were Imereti and especially the Akhaltsikhe region; architectural art reached its zenith, with Pitsunda made the seat of the Catholicos-Patriarch, and many remarkable churches were constructed, of which I will mention only those that still survive in Mingrelia and Abkhazia and which I had the opportunity to visit. These include Martvili, Nokalakevi, Zugdidi churches, Tsaishi, Khopi, Bedia, Mokvi, Dranda, Nikopsia, and some others. Of these, perhaps only Dranda and the Nokalakevi church date back to the Greek era, specifically to the time when the Pitsunda church was built, as they all bear traces of the most ancient style. The rest are monuments of the Abkhazian-Georgian dynasty and were constructed between the 10th and 13th centuries. The names of the kings who built them have been preserved in chronicles and partly in wall inscriptions.

The finest of these churches are Bedia and Mokvi. Both have long been abandoned, with their roofs and walls now overgrown with dense vegetation and ancient trees; however, their style is a model of architectural art. Mokvi is especially remarkable; there is nothing like it in all of Georgia. It stands by the Mokvistskali River, surrounded by a double enclosure; its walls are grand and majestic, clad inside and out in finely hewn stone. Its appearance is stunningly beautiful: the overall character and details are elegant and symmetrical. The painting is barely visible but was superior to that in other churches I have seen. The galleries encircle the entire building up to the altar projection; the floor is paved with multicoloured marble tiles; the columns of the iconostasis were made of marble, and the fragments show how meticulously they were crafted. The building, in general, has suffered very few damages; most of it remains intact despite one and a half centuries of neglect. Mokvi was erected by the Abkhazian king Leon in the 10th century and was decorated, according to Jerusalem Patriarch Dositheos, who visited the church in the 17th century, by some Georgian monks, including Nicholas, who belonged to a noble family and was known for his high education and travels through Italy. The icon of the Mother of God from Mokvi is kept in the Khopi monastery. Mokvi could be easily restored with relatively modest expenses. The new road, as noted earlier, will pass right by the church, and a Cossack post will be stationed within the new enclosure, allowing those inclined to savour the experience to admire this finest monument of the best periods of Georgia.

I have no doubt that a major road once passed by Mokvi and Bedia during the reign of the Abkhazian-Georgian kings and later, for such monuments would have been built specifically along major roads; I have no doubt that there should be remnants of bridges here—they have been seen, at least, on the Tskhenistskali. The population was denser here, as evidenced by the numerous ruins of beautiful churches made of hewn stone in the surrounding areas.

During the reign of the Abkhazian-Georgian Bagrationi dynasty, the borders of Abkhazia and Mingrelia were clearly and firmly established: the former was bounded between the Ingur and Kapetistskali, while the latter lay between the Tskhenistskali and the Ingur. The rulers of both mixed principalities—Dadiani and Sharashidze—have been known since the time of the Abkhazian-Georgian kings. It is unknown to which lineage the Dadiani belonged, but the name 'Dadiani' was derived from the name of the Dadia castle and the river of the same name, which now flows as the Ertis-tskali in Samurzakan. Chronicles trace the origins of the Sharashidze family to the Shirvan emir from the Beni-Shaddad dynasty, who was resettled in Georgia by David the Builder. The members of this family received their hereditary rights under Queen Tamar, and since then, the Sharashidze dynasty has remained unbroken; however, the Dadiani dynasty was interrupted only in the 17th century, and from that time, a new dynasty took its place.

+ Excursion to Samurzakan and Abkhazia [Excursion au Samourzakan et en Abkasie], by Carla Serena

+ The solitude of Abkhazia, by Douglas W. Freshfield (1896)

+ Challenging Georgian Narratives (Response 2): A Further Exploration on Abkhazia by Stanislav Lakoba

The Dadiani and Sharashidze gained full independence alongside the Gurieli and the Atabegs of Akhaltsikhe in the 15th century, shortly after Georgia was divided into three kingdoms. Under their rule, feudalism became firmly established, especially in Mingrelia, where it took on a fragmented character resembling that of Western Europe in the Middle Ages. The monuments of the Dadiani consist of churches and monasteries, including a restored church and a castle adorned with numerous icons in silver and gold settings, as well as precious stones with inscriptions, which were reminiscent of Spanish military churches. Numerous similar inscriptions have been found by archaeologists in Ilori, Khopi, Tsaishi, and Tselatkhani, often mentioning Levan II, who lived in the 17th century. Belonging to the first dynasty, he was known for his ruthless character, celebrated for victories over the Imeretian kings, the Gurieli, and the Sharashidze, and for expanding the borders of Mingrelia as far as Nikopsia, claiming for himself a significant portion of Abkhazia.

The mutual quarrels of the rulers during the period of independence and the increasing Turkish influence along the Black Sea coast led to prolonged disorder in both regions. Even Chardin, who visited Mingrelia shortly after the death of Levan II, found the area in a deplorable state: the religious spirit had weakened; lawlessness was widespread; familial bonds were weakening; and particularly prevalent was the trade in captives, which had become the main industry for both Abkhazians and Mingrelians. Most of the beautiful Mingrelian girls ended up in Turkey; the girls were taken into harems, while the boys, often purchased by Ottoman eunuchs and Egyptian Mamluks, frequently rose to high ranks. The Abkhazians and Samurzakanians distanced themselves from the ecclesiastical authority, and Mingrelia was at risk of doing the same if not for the timely implementation of new measures, the re-establishment of influence, and the prevention of further decay.

In concluding this article, I must say a few words about the current situation of the tribes I have described. These tribes, due to the peculiarities of their local conditions and way of life, have developed distinct characteristics. The Mingrelians have delicate, more feminine facial features; there is little masculine beauty among them. Even the typical Mingrelian has a refined, elegant look; and the women of the peasant class are strikingly charming. The further you go inland, the more rugged the Samurzakanians and Abkhazians become, with masculine beauty prevailing over feminine. The Mingrelians, through their interactions, have become polite and ingratiating. In contrast, the Samurzakanians and Abkhazians carry themselves freely and proudly, saying that being subordinate felt as natural to them as leaning on a hand. Generally, they and others are endowed with admirable abilities, which, with proper development, promise much for the future.

They live, as is well known, in isolation, rarely more than 5–10 families together, and mostly alone; they have customs that have been preserved since ancient times, which were often the source of complaints from European travellers and Slavic wanderers. They remain on the lowest rung of civility; they are so unsociable that at the sight of a stranger, they run and hide like frightened hares. Their language is peculiar in expression, and they are extremely reticent. This opinion may seem exaggerated because these tribes, due to their timid nature and low morals, lack will and assertiveness. However, there is also a positive side that has not been sufficiently recognised: if they are given a push, their economy will develop on a broad scale, and their country could become another Switzerland.

The current way of life is shaped by local conditions, and we should not disregard them. Perhaps, we will live to see a time when their lives will significantly improve. In the native population, especially in Mingrelia, there are already visible efforts toward improvement: they are clearing forests, striving to settle along the roads; they display great industriousness, raising livestock, and cultivating ghomi, maize, rye, and flax in abundance. Officials here told me that the Mingrelians today are no longer what they were before the war; they have become more active, especially in the last two years, and their prosperity is more apparent. Thanks to their natural entrepreneurial spirit, many of them seek employment beyond their homeland, buying young wines and other local products in Samurzakan and Abkhazia, and setting up taverns along the trade routes where there is the greatest need.

In general, the natives can gain substantial benefits from good examples, and they can find these examples in Okumi and Gagra, Zugdidi, and Sukhum. In these places, there is currently noticeable activity. Two years ago in Okumi, there was only a single house belonging to a priest; now, thanks to the efforts of the official, Mr. Chernjavsky, a convenient government building has been constructed, a street laid out and lined with shops; a church and barracks are under construction. Similar developments are taking place in Gagra; the quarters for the battalion commander, officers, and lower ranks have been completed and are in use; the church is well-equipped, and the small garden in the fortification has been planted with olive trees, among others. Zugdidi and Sukhum are growing rapidly; around Sukhum, forests are being cleared, swamps are drained, and canals are being dug; straight, wide streets are lined with two-storey houses. A Greek resident named Metaksi, who has lived in Abkhazia for over 30 years, constructed a fountain at his own expense for the public benefit, and water was brought to it from outside the town. Native landowners are acquiring properties in the city and building there, with many also erecting homes on their estates and striving to adopt European agricultural practices. There is no doubt that all this will have an influence on the general population.

The natives no longer shy away at the sight of foreigners; the vices for which they were criticised are encountered less often, and this is largely due to the spread of Christianity among them. Much progress has been made in this regard. In Abkhazia, Christians are scattered almost everywhere, even up to the very border with Dzhigetia, which can be easily observed by the presence of pig herds: there are none where only Muslims live. On the right bank of the Kodor River, several villages have requested priests and provisions for church construction from Prince G. R. Eristoy. On the left bank, almost the entire population is Christian. Among the landowners of Abkhazia, the majority have converted. As for Samurzakan, according to statistical information presented in 1857 by the local dean, Archpriest Machavariani, to the governor-general, out of 2,964 households in 36 villages, only 20 were Muslim, and out of 535 noblemen, 52 were unbaptised males. Currently, there are 16 parishes, meaning there are very few Muslims, and this achievement is largely due to the efforts of Machavariani.

Archpriest Machavariani is a true missionary, skilled, knowledgeable, and dedicated. He has learned the Mingrelian language, into which he has translated the holy liturgy; he has been in Samurzakan since 1850, annually educating no fewer than 25 Samurzakanians without charging them any fees, teaching them, in addition to Russian and Georgian, basic arithmetic, catechism, and writing. In one village, I witnessed his moral influence on those he had converted and their attitude toward him: his instructions were listened to with focused attention, and his remarks were accepted with filial obedience and evident gratitude. It would be desirable for proper attention to be paid to such individuals.

May, 1860, Kutaisi.

Dmitry Bakradze

Gazeta Kavkaz (No:49), 1860 pp. 298-299.

____________________

With reference to the priest Machavariani, please see (―Ed):

Konstantin Davidovich Machavariani, Opisatel’nyj Putevoditel’ po Gorodu Suxumu i Suxumskomu Okrugu. S Istoriko-ètnograficheskim Ocherkom Abxazii [Descriptive Guide to Sukhum City and the Sukhum District. With a Historico-Ethnographic Essay on Abkhazia], Sukhum, 2009. Originally published in 1913.