Obituary | A Hero of His Times: Yuri/Musa Shanibov, 1936-2020, by Georgi Derluguian

![Musa [Yuri] Shanibov (Circassian: Щэныбэ Юрэ) (1936-2020) Musa Shanibov](/aw/images/people/Musa_Yuri_Shanibov.jpg)

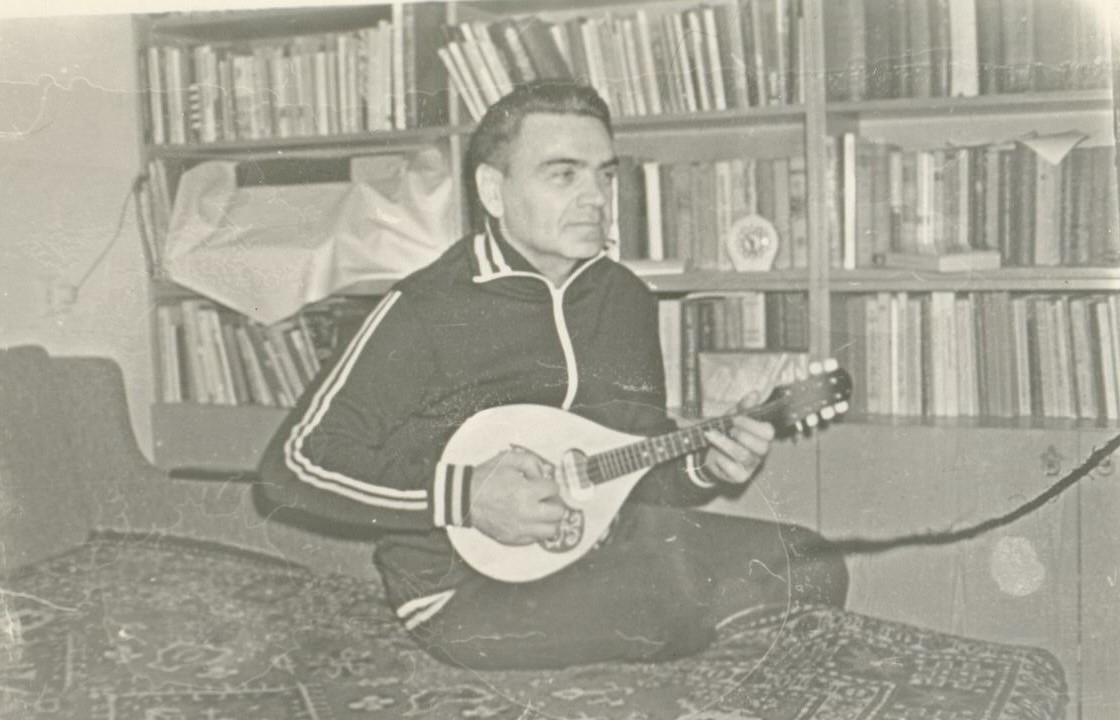

Musa [Yuri] Shanibov (Circassian: Щэныбэ Юрэ) (1936-2020)

Yuri Magomedovich Shanibov lived a rich (Soviet) biography that fully reflected the changing historical epochs. Back in 1997 the world-famous French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu felt so intrigued by the photo of the distinguished-looking Shanibov, always in his Caucasian sheepskin papakha hat — while reading in Russian one of Bourdieu’s own books — that the exotic photo ended up on the wall of his office at the Collège de France. But could I ever ‘briefly’ explain to Bourdieu the trajectory of his ‘secret admirer’ from the Caucasus? In the end, it took me a whole monograph.

Many details of this biography seem uncertain. To begin with, Shanibov himself admitted that he could be a whole year older than his official birthdate in 1936. The record-keeping was rudimentary in mountain-villages. Or, perhaps, his mother, widowed in 1942 during the Nazi advance on the North Caucasus, tried to extend by another year the wartime ration-cards for her children. Yet this very uncertainty truthfully reflected the vagaries of its epoch. It is no less historically illustrative that all the Shanibov children would achieve higher education and distinguished careers, rising, in parallel with the rest of Soviet Union, after 1945. The name ‘Yuri’ emerges in this perspective not as any concession to the purported Russification of Soviet Circassians but rather as a marker of cosmopolitan modernization. Yuri was the name of his father’s best friend from a large construction site in Nalchik during the 1930s, and since 1961 ‘Yuri’ had become firmly associated with Gagarin, the first cosmonaut. The rural name ‘Musa’ was reclaimed publicly only in 1989 with Shanibov’s assuming the presidency of a grouping styled at the time ‘The Assembly of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus’, which in 1991 was transformed into ‘The Confederation of the Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus’.

Shanibov is playing the mandolin at home (1970s)

Yuri Shanibov barely knew his father. Instead, like so many upward-mobile orphans in his generation, he adored the Great Stalin. This youthful faith was shattered in the early 1960s when Yuri, already a district attorney, gained access to the old police-file on his father and realized with disgust that the denunciations came from their neighbour, who was still alive. What did Shanibov do? Nothing. He let the enemy live with his guilt. Stalinism belonged in the past. The Soviet Union was moving into the future of new technologies, prosperity — and people’s democratization!

Shanibov was a typical shestidesyatnik, a man of the sixties, optimist and activist. He saw his initially rapid career of law-enforcer and secretary in the local Young Communist League (Komsomol) as a personal mission, promising to correct all wrongs and build a better kind of socialism. Ironically, this faith in democratic socialism would stall Shanibov’s career after 1968. The epoch of Brezhnev brought official hypocrisy and the fear of any action which could be tainted by the runaway ‘Prague Spring’ and other anti-bureaucratic rebellions across the Soviet bloc. In the following two decades Shanibov stayed comfortably established as lecturer in Social Sciences at the local university in Nalchik. He even enjoyed student-popularity for daring to debate self-governance and incorporate Freud in his lectures on ‘scientific communism’. But his academic career stagnated along the rest of the Soviet Union’s economy and society in those uneventful decades.

Shanibov is lecturing to students (1970s)

It all suddenly changed again after 1985 with Gorbachev’s proclamation of his perestroika-reforms intended to ‘rejuvenate’ Soviet socialism. Like so many Soviet intellectuals momentously achieving public acclaim in those days, Shanibov only needed an opportunity and larger audience to speak his mind. In Nalchik, he soon became a celebrity as the leading critic of local bosses and a self-declared supporter of Gorbachev in Moscow. By 1989, after four feverish years of perestroika filled with disasters like the Chernobyl nuclear fire and haphazard or ill-advised moves to undo the legacies of Stalinism and overcome bureaucratic inertia, Gorbachev’s once hugely hopeful authority appeared in tatters. Now rudderless, the Soviet economy was plunging from stagnation into real chaos. Exploiting the manifest weakness of Moscow, dozens of national republics grew openly defiant. Their ex-communist bureaucracies, in a desperate rush to save themselves, competed with national intelligentsia in reasserting sovereign rights for their economic resources and ethnic politics. In many tragic instances this chaotic rush reignited conflicts among the neighbouring nationalities which, since the Civil war of 1917-1921, had been rigidly incorporated in the USSR. The Georgian-Abkhazian clashes were but one such instance.

+ Yuri (Musa) Shanibov: a personal recollection, by George Hewitt

+ Aslan Bzhania: the name of Musa Shanibov embodies the bright ideals of freedom and justice

+ Musa Shanibov addressing Abkhazians and Circassians (Abkhazia, 26 August 1989)

+ How nations united: Formation of the Confederation of Caucasian Peoples

The political instincts of Musa Shanibov, as he now called himself, suggested a radical shift towards nationalism. Never a military man, he rather used his professorial oratory to preach interethnic peace alongside the struggle for ethnic self-determination. This contradictory programme found expression in the ephemeral organization whose name reflected Shanibov’s own grandiloquence: Confederation of the Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus. Purportedly, it was to unite all indigenous groups of the region from Daghestan on the Caspian to Abkhazia on the Black sea. After two more years of convening congresses, conducting inconclusive debates, and adopting declarations, Musa Shanibov consolidated his political reputation of wise elder across much of a very diverse region: no small feat. Though never elected to any formal legislature, his methods and inclinations were essentially parliamentarian. Yet, amidst the 1991 Soviet collapse, Shanibov found himself a revolutionary leader, the latter-day Garibaldi of the Caucasus. In those days, huge rebellious crowds gathered in the main city-squares, from Makhachkala, Grozny, Vladikavkaz to Nalchik, Maikop, Lykhny, and Sukhum. Shanibov’s famous oratory found itself in great demand. His negotiating skills on the brink of fighting equally impressed many. Yet in 1992 he was misidentified and arrested as a leading separatist by the Russian security-service. Before this mistake could be corrected, Shanibov escaped, apparently on his own, amidst a cloud of conspiratorial rumours. Yet, if there ever existed a moment to elude the KGB, it was in the raging chaos of 1992.

Shanibov with Kabardian volunteers. Abkhazia (Autumn 1993)

The life of Musa Shanibov was full of ironies, the majority of them bitter. He started as a law-enforcer only to become a fugitive rebel. The former socialist reformer ended up a nationalist. His political style was parliamentarian, yet Shanibov’s finest — and darkest — hour arrived in the Abkhazian war of independence from Georgia, itself a rebellious separatist republic from the USSR. He never fought with gun in hand, yet his political career was ended by a bullet — a stray bullet from his careless bodyguard. The herbal medicine for wounds, whose ancient secret was carried down the generations in a refugee Circassian family from the Middle East, boosted Shanibov’s morale. Still, he had to spend long months in Russian hospitals — where he studied the political sociology of Pierre Bourdieu.

The ultimate irony emerges from the fact that Yuri Shanibov could live to his natural age of 83 (or was it 84?) His politics of unity among the Caucasian mountaineers was reduced to propaganda already in the course of the Georgian-Abkhazian war, when guns took precedence. I called on Shanibov at his home in Nalchik, a modest Soviet-era apartment, shortly after the abortive armed rebellion of local Islamists in October 2005. He responded with bitter resignation: “Shanibov is safe because he is forgotten. The boys who perished under my windows yesterday were small children in the days when my name caused the Caucasus to tremble.”

The Day of Remembrance of the Russian-Caucasian War. Shanibov (on the right). Abkhazia (21 May 2011)

Probably the best characterization of Shanibov’s improbable life was suggested by a fellow-professor at Nalchik University when I was gathering materials for my monograph: “Do not judge our Yuri too strictly. His whole life was spent defending really the same principle of democratic autonomy. It is the reference-groups of democratic autonomy that have been shifting over the epochs, from young socialist workers and intelligentsia to small nations and their pan-national Confederation.”

Georgi Derluguian is Professor of Sociology at New York University (Abu Dhabi) and author of Bourdieu’s Secret Admirer in the Caucasus: A World-Systems Biography. (University of Chicago Press, 2005)