Thirty Years' War. How the Georgian-Abkhazian war changed history, and history changed the war

A Georgian armored vehicle drives down a road. July, 1993. Sukhum, Abkhazia.

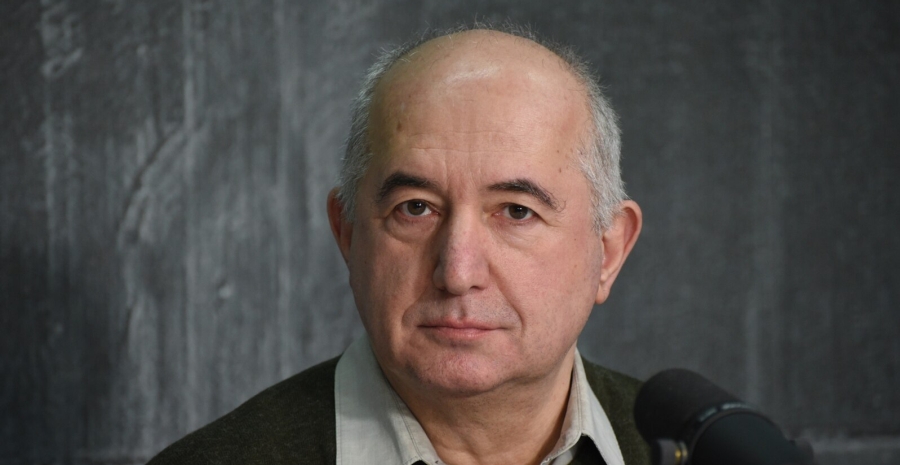

Interview with Arda Inal-ipa and Paata Zakareishvili

Ekho Kavkaza -- "We continue the “Thirty Years' War” project dedicated to the anniversary of post-Soviet conflicts. On 14 August 1992, the Georgian-Abkhazian war began. The questions to what has been rethought in thirty years, what still remains unsolvable, and what might be the starting-point of improvement are the topics we discuss with the guests of the Non-Round Table – political scientists Arda Inal-ipa and Paata Zakareishvili."

– Arda, I watched how the 30th anniversary of the start of the war in Abkhazia was being marked, and I tried to understand how this story is perceived now. Is there some kind of new understanding, a new understanding of what happened, or is it already such a fixed attitude, akin to how the 9th of May was perceived in Soviet times?

Arda Inal-ipa: Both. There are already well-established rituals associated with the war – all this permeates our entire life, our society – some memorable dates that are very important for every Abkhazian. But there is also a new understanding and a critical attitude to the past years. Still, life does not stand still, and it seems to me that many illusions have dissipated, many conclusions have been drawn. But still, the main thing is that if a people is united and strives for self-preservation, for development, then it is very difficult to defeat it. If in 1992 very few people believed (I mean external observers) in the victory of the Abkhazians in the confrontation with a stronger and more numerous Georgia, then in 1993 it became clear that, if the people really clenched into their fist, then they would be able to win their freedom. And the price of this freedom is just as high, and it is just as appreciated as the greatest achievement. Another thing is that there were many moments associated with living in peace; there have been many disappointments.

– Batono Paata, I would like to ask you the same question: 30 years have passed, we can say that two generations have grown up, and the refugees, on the contrary, are getting older… Is there any new understanding of this date in Georgia?

Paata Zakareishvili: Yes, in fact, this is a very strange kind of feeling in Georgia. In Abkhazian society they consider themselves winners, and accordingly on the basis of this victory they construct that which is very important for them. And in Georgia it is believed that we lost, and we are looking for reasons why this happened, and we blame everything on Russia. And then 2008 was added to this – that was also a very tough defeat, no doubt at the hands of Russia. Therefore, it all somehow got mixed up – all these events on the territory of Georgia that took place and which left the feeling that it was Russia that has been fighting with us. Until 2008, it was still possible somehow to divide Georgian-Russian and Georgian-Abkhazian relations, and many tried to do this. I personally tried very hard to prove that we must find a common language with Abkhazian society and that must there should be a separation, one from the other, of Russian imperial interests and Abkhazian interests, which they want to protect. And now this situation has worsened, now there are fewer and fewer people standing by such positions as those to which I cleave, and the more and more vividly so, especially against the backdrop of the Ukraine.

– If you try to prioritise attitudes towards this, what will be the main issue –return of refugees, the victims, territorial losses, national pride? Now, if it were possible to divide all this in terms of importance, what would your hierarchy look like?

National pride exists, but it is rarely spoken of. Basically, two positions are voiced: the restoration of territorial integrity – Russia ripped it away from us – and the second, also a very tough topic, is the return of refugees. These are the two topics that are constantly under discussion in Georgia, and they are the two topics that are in no way acceptable to Abkhazian society. This hinders dialogue – we cannot somehow distance ourselves from these topics and say that there are a lot of other topics (besides the restoration of territorial integrity and the return of refugees) and that these issues can be returned to later in a new context. There are people who make sure that their sacred topics are under no circumstances removed from the pedestal. These are almost unshakable topics.

Arda Inal-ipa: This post-war period can be roughly divided into three stages. The first was until 2008, when Russia recognised the independence of Abkhazia. Prior to this, Russia did not in fact recognise Abkhazia, and you know that there were years during the Chechen war, in particular, when we were under the most severe sanctions – not only from the international community, but also from Russia, and the CIS countries – when only women, old people and children could cross the Russian-Abkhazian border; people even died there in stampedes. Those were terrible years.

Those people who say that there was not and is not a Georgian-Abkhazian conflict simply rub out these years. Abkhazia was completely alone, under sanctions for a war that was unleashed on the territory of Abkhazia. It is clear that there were consequences of this war in the form of numerous refugees along with their problems, but nevertheless... Russia helped with humanitarian aid, and there were international organisations that also helped in the matter of survival, but there was absolutely no such help in the formation of the state. But, unfortunately, Paata is absolutely right that, especially after 2008, there is almost no alternative version. It is very difficult for Abkhazia to fight this, but, unfortunately, this is dictated by many political actions in relation to Abkhazia, or rather, their absence.

The second stage – after 2008 until 2014, when an open conflict between Russia and the Ukraine began, and then here we have the third period, to the present day.

Arda Inal-Ipa is a civil society activist, based at the Center for Humanitarian Programmes, Sukhum.

+ Arda Inal-Ipa: It’s no wonder that today people recall the events of 1921

+ Arda Inal-Ipa: "Perhaps we shall be able to learn from the difficult experience of recent days, God willing"

+ Don't call us 'occupied', by Arda Inal-Ipa

– Arda, it seems to me that the “subjunctive mood” [sc. the mood used to express a hypothesis. speculation or supposition] is one of the most interesting in history. If we consider, nevertheless, the range of all possible happenings – after all, in Abkhazia the possibility of some kind of common state was supposed for quite a long time, and, if this had come about, how might all this look now? Or was the collapse inevitable anyway?

Arda Inal-ipa: Literally on the eve of the invasion of the troops of the State Council [sc. if Georgia], a draft for a federal structure for the state was published, whereby Abkhazia and Georgia would have been equal subjects in a unitary state. The author of this project was Taras Mironovich Shamba, and there were people who were ready to discuss it seriously, and it really was a topic that could have been a topic for long, serious negotiations. But, unfortunately, the war erased these plans, and I think that after the war, even experts who believe that federalism is the solution to many conflicts, such as, for example, Bruno Coppieters, were forced to admit that after the bloody events this remedy would no longer work. In fact, it seems to me that there was no chance and that there still isn’t. These traumas of war go very deep.

Paata Zakareishvili is the former State Minister for Reconciliation and Civic Equality from 2012 until 2016.

– Paata, those for whom this is already history admit that there were some mistakes on the Georgian side, is there an understanding that this could have been avoided?

Paata Zakareishvili: An understanding that some mistakes were made sometimes slips out. Just recently there was an interview with one of the then-officials Sandro Kavsadze, who was at the time at the right hand of (Eduard) Shevardnadze, and he now admits that very gross mistakes were made. But it's pretty late now. In any case, the expert-community unequivocally understands that, of course, huge mistakes were made, first of all, the decision to send troops of the armed forces into the territory of Abkhazia should not have been allowed under any circumstance. But when this position, let's say, is head-lines in politics, when these texts get into politicians’ hands, it all disappears. In the rhetoric of politicians, we – Abkhazians and Georgians – are brothers and sisters; in such a context, the Prime Minister and other officials have been speaking in recent days. At its most extreme –some kind of toasts are proposed. Then there’s the other extreme – that no-one asks the Abkhazians their opinion about anything there, because Russia just does everything there, and, naturally, no-one wants to bother trying to understand it.

The truth is that it was quite a difficult situation. There was an internal confrontation, there was a civil war between Shevardnadze's supporters and the former president (Zviad) Gamsakhurdia. These events were later carried over into Abkhazia, and the Georgian authorities, Shevardnadze, took advantage of the moment: he thought, “Let's at least solve the Abkhazian issue now”, because it was impossible to resolve issues with Zviad Gamsakhurdia. By the way, after the end of hostilities, this confrontation between Shevardnadze and Gamsakhurdia continued in Western Georgia, and only by the time Georgia joined the CIS did this civil confrontation end in Georgia itself.

Also in Russia there was confrontation. We must not forget that there was a constitutional crisis. On 30 September the armed forces of Georgia left the Abkhazian territory, and just five days later the White House - the Russian parliament – was bombed. Two Russias, two Georgias - this found reflection in Abkhazia, and the entire Caucasus. It was a very complicated tangled ball. And it was exceptionally difficult to make sense of it, such that one often had to work blind.

As for the Abkhazian side, they had a very clear and unambiguous policy - defend and play on four sides – with Russia’s two sides and with the two in Georgia. The Abkhazians were more monolithic, and they clearly knew what they wanted.

Our politicians do not understand this and do not want to understand it. Russia has its own role, a terrible and immoral one, but I believe that we must deal with our problems. We, unfortunately, have not been able to resolve this through dialogue, through mutual understanding with the Abkhazian side – that of which they have been afraid, their fears, the risks they see. We have been unable to achieve this, although there were attempts before the war.

Arda spoke about one document. There were other opportunities – the possibility of conducting some kind of negotiations in the Supreme Council of Abkhazia, there were some opportunities with different parliamentary factions, but, unfortunately, those resources, those forces that were striving for war, turned out to be stronger in the end than the resources of those people who did not want to allow war.

+ Abkhazia [14 August] 1992-2022

+ Beslan Kobakhia: ‘This war should be ended by those who started it’

+ In Defence of the Homeland: Intellectuals and the Georgian-Abkhazian Conflict, by Bruno Coppieters

- Arda, in Abkhazia, is there such a historical gap between what was and what might have been in order that the war could have been avoided?

Arda Inal-ipa: Probably, such persons were not the majority, but still there were those who really counted on the return of representatives of the Diaspora, since, as you know, most of the Abkhazian people are located outside of Abkhazia – those who have not lost their ethnic self-consciousness, despite the fact that these ties were interrupted for many years in the Soviet Union, but they were instantly restored when the possibility of travel and contacts arose. Therefore, there was such a hope that an open Abkhazia would be able to increase its population, solve the problem over the language – i.e. there were hopes that it could be done peacefully.

– Now is it not customary to recall that, in principle, this was possible?

Arda Inal-ipa: Thank God, in Abkhazia, despite all the problems, democracy and freedom of speech have been preserved, and during some discussions, round tables, people openly talk about what could have been. But, unfortunately, reality sets the tone for all discourses and narratives in Abkhazia.

– The most important narrative that we mentioned is the Russian narrative. How has this narrative changed, how has the perception of Russia's role in Abkhazia itself changed over the course of 30 years?

Arda Inal-ipa: Firstly, there’s the fact that very often Moscow was the centre of decision-making, which the Abkhazians have always regarded with hope. And, in fact, some very important issues were resolved in Moscow, when, for example, the Abkhazians were indignant at some kind of pressure from Tbilisi, this happened with some success, but then none the less there was some kind of centre in Soviet Union. Naturally, such inertia in this kind of attitude, of such hopes still remains strong.

On the other hand, the world has become very complicated, and our society sees that Russia has its own interests and a completely legitimate right to defend its interests, even when they do not coincide with those of Abkhazia, although we are strategic partners. Well, there was a period when Abkhazia was under blockade...

The attitude is changing a little, because our authorities have not chosen the right strategy in their relations with Russia, when it seemed to them that the more they can beg or agree on some kind of financial assistance, the better, and this is such a victory for them. In fact, this has led to dependence, to passivity, to the irrational use of our resources, to weak economic policies.

+ Stanislav Lakoba: "If Yeltsin had been opposed, the war in Abkhazia would not have started"

+ 14 August 1997, Vladislav Ardzinba - in Tbilisi. How did this come about?

+ The Georgia-Abkhazia peace process: Agreements Database

Naturally, this has also changed Russia's attitude towards Abkhazia. That is, Russia saw that Abkhazia is ready to be such a satellite, without any political subjectivity of its own. And Abkhazian society didn't like how Russia's attitude was changing, and it has givcn rise to new processes. So this is indeed a very complicated process, and you probably observe how Abkhazian society, economically dependent on Russia, still allows itself such risky steps to defend its sovereignty.

An objective observer, of course, would have had to appreciate that life in Abkhazia is far from the life of such a puppet society. Now, when there are hopes on the part of our government that the oligarchs, including Russian ones, will be able to change the economy of our country for the better, this causes a huge protest in society.

– Paata, I remember the time, even before (Mikhail) Saakashvili, when Abkhazia, like South Ossetia, was somewhere at the end of the top ten, even the start of the second [group of ten], on the list of problems for the Georgian layman, as there were things much more important. In your opinion, is it really so important for Georgia – this Russian narrative, or is it, as follows from the speeches of politicians, that the 14th of August has, in general, become just such a set of toasts, as you said?

Paata Zakareishvili: I don’t remember about the second ten, but places 7-8, yes, were occupied by these topics in sociological research. But as soon as something happens – a tense situation, a pre-war context – a dormant situation immediately turns hot one and immediately begins to occupy places 1-2. Then months somehow pass, and it falls back, as unemployment, various geopolitical challenges or others take the first place. But the events in the Ukraine were just able to rouse this topic again. Although no-one remembers the Georgian-Ossetian situation of the 1990s, everyone remembers only 2008. With Abkhazia, thank God, since the 90s there have been no serious clashes, so we always mark the 90s, and somehow there’s been a coalescence with August – the events of 1992 in Abkhazia and of 2008 in South Ossetia. Accordingly, Abkhazia always remains in the 90s, and South Ossetia – in the modern period.

Against this background, of course, the topic of Russia is becoming more and more permanent, firmly fixed on the agenda of the opposition. Moreover, it is obvious, and in my opinion too, that the Georgian authorities are doing almost nothing today in order to start moving peacefully and to remind the world-community and to include the Georgian topic on the agenda of today's world-events, not only in the context of the Ukraine. A lot is happening, and here one could include the Georgian theme, but by means of absolute silence on the part of the Georgian authorities we are thus handing Abkhazia and South Ossetia over to Russia. This is how the narrative is now being formed. Usually it’s the opposition parties, but even among a significant part of civil society that does not deal with conflicts there is a feeling that all this is just – Russia.

– But there is some segment in Georgian society – civil society, the expert-community – in which there is some kind of constructive settlement programme that does arises not from this idea but from the fact that to some extent, one way or another, Abkhazia has succeeded, and now the settlement-formula is not quite the same as it could have been 30 years ago?

Paata Zakareishvili: Yes, I think I also belong to this group. This group is not numerous, but very competent and qualified. At least when there is a question of discussing unresolved conflicts, both television, and the media, and representatives of the opposition, and even the authorities turn to this group. It says that it is imperative to communicate with the Abkhazian side, to take into account its interests, to take into account the reality that is being created in the world and in the region – all together, in the context of Karabakh and the Ukraine, all this must be taken into account.

Eduard Shevardnadze and Vladislav Ardzinba in Tbilisi. 14 August 1997.

– What are the summative points that this group can offer?

Paata Zakareishvili: That we must necessarily take into account the interests of the Abkhazian side – well, I mean the Ossetian side too. But the Abkhazian side is more vocal about its positions, unlike, unfortunately, what comes from South Ossetia. The Abkhazian side has constant demands that there be agreement on some kind of document regarding the non-resumption of hostilities. I am for it. It is necessary to discuss those topics that concern them. There are other topics that the Abkhazian side proposes: transport-issues, trade-issues – there are a lot of issues. By the way, before the Karabakh war there was a serious discussion in Abkhazia about dialogue with the Georgian side. Unfortunately, after that it stopped, and the fault was ours too.

There is now the new context for the Ukraine, as well as some challenges, the Black Sea context. In Abkhazia, there aren’t always the most successful opportunities to resolve issues – I have in mind the attitude towards Russia and relations with Georgia too. Therefore, Georgia should be the initiator on many issues. The ultimate political decision is lacking – political will. Now the Georgian authorities have other challenges they are fighting for survival, for maintaining power, and neither for society nor for the authorities is conflict-resolution the most important topic now.

- Do you have any strategic idea as to what kind of relations there might be between Abkhazia and Georgia?

Paata Zakareishvili: Finally, the Georgian authorities have recently begun to develop some kind of new strategic view, because the last one was in 2010, but the Ukrainian events put a stop to all this; currently everyone is waiting to see what will happen in the Ukraine. But, in any case, there is no written document, but there is a clear understanding in civil society: we cannot resolve Abkhazian or South Ossetian issues without communicating with the Abkhazian or South Ossetian government. We offer them a lot of things, without even asking the Abkhazians – the economy, a fifth or tenth – but the Abkhazians do not accept, because all this has not been agreed with them. The main problem is not that there is no strategy, but that we do not discuss what this strategy might be. I am categorically against Tbilisi nurturing and proposing such a strategy. This should be mutual and agreed upon by both parties.

Arda, I understand that Abkhazia has fewer opportunities for initiative; in terms of football, it is forced to play second. But does it have any constructive strategic ideas about it? And, if possible, please answer Paata's question: is Abkhazia ready for what Georgia can offer? Because just in the last few months I have certain doubts about this...

Arda Inal-ipa: What I hear from Paata about the need to take into account Abkhazian interests, to talk with Abkhazia, I completely agree with this. But Georgia has taken some steps that prevent this. For example, the Law on Occupied Territories. In fact, I don't think it reflects reality in any way. Yes, we have a Russian base, but it appeared as a result of the fact that there was a real threat from Georgia, and it [Georgia] does not sign this agreement on the non-resumption of hostilities. If we are an occupied territory, then who is Georgia going to talk to? That is, there is ab initio such a contradictory position on their part. It seems to me that it has driven into a dead end what, in general, is the quite pragmatic process that could develop.

Yes, the issue of the need to conduct negotiations has been discussed; yes, there is resistance to this in society, and then we abandoned this concept of a multi-level dialogue with Georgia. But this issue continues to be discussed in various political and public circles, and, in principle, Abkhazia is ready to discuss issues of unblocking transport-links, etc. But now this Law on the Occupied Territories is really destructive, both from a regional and bilateral point of view, and, of course, from the point of view of the development of Abkhazia.

Basically, there are a lot of questions. And, yes, now the political contradictions are insoluble, but there are a lot of humanitarian and economic issues. There are issues that might generally be raised at a regional South Caucasian level: environmental issues, transport-issues, tourism-issues, for example, and this could establish some kind of constructive relationship, on the basis of which it would be possible to start more difficult ones, so to say, political contradictions. So, it seems to me that now the ball is fully in Georgia’s court.

This interview was published by Ekho Kavkaza, and is translated from Russian.