Stanislav Lakoba: "Sakharov had an interest in Abkhazia through Iskander"

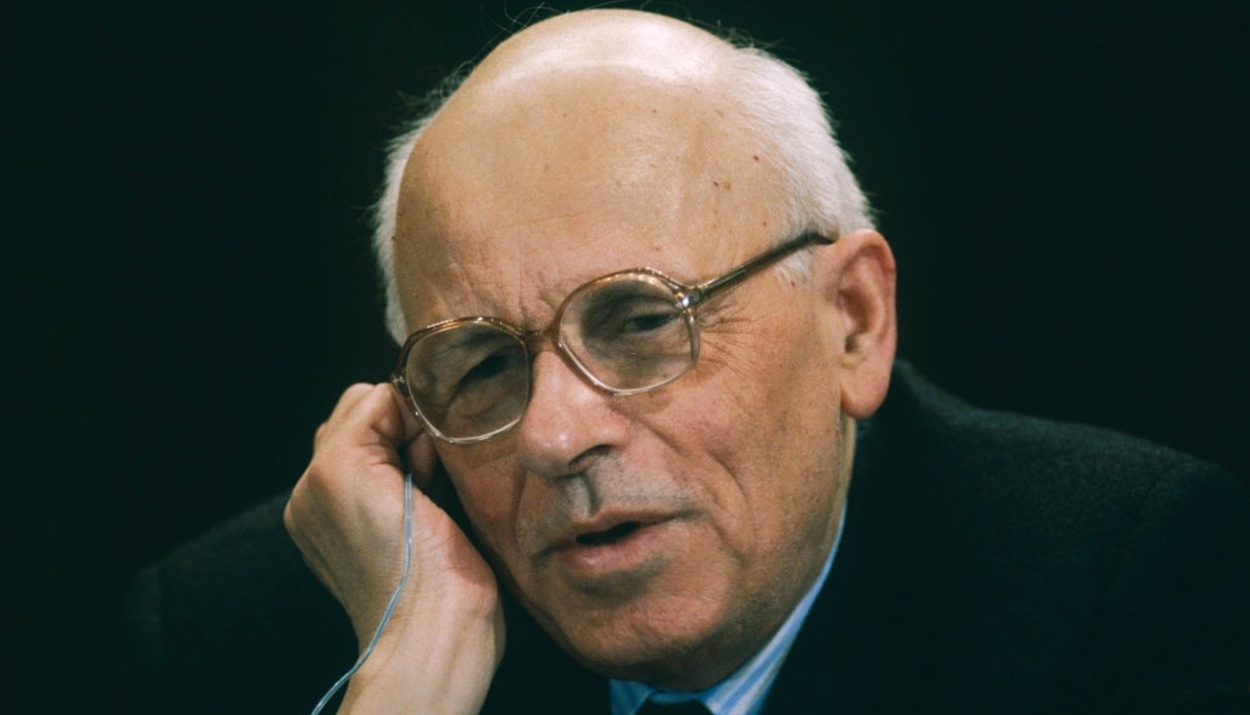

Andrei Sakharov (1921-1989) during a Press conference in 1988.

On 21 May, the world celebrated the 100th anniversary of the birth of Academician Andrei Sakharov, a man about whom another academician Dmitry Likhachov once said: “He was a real prophet — a prophet in the ancient, original sense of the word, that is, a person who called his contemporaries to moral renewal for the sake of the future."

Wikipedia speaks about him as follows: “Soviet theoretical physicist, academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences, one of the creators of the first Soviet hydrogen bomb. Three times Hero of Socialist Labor. Public figure, dissident and human rights activist, People's Deputy of the USSR ... Winner of the 1975 Nobel Peace Prize. After statements condemning the entry of Soviet troops into Afghanistan, he was deprived of all Soviet awards and prizes and in January 1980 was expelled with his wife Elena Bonner from Moscow. At the end of 1986, General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Mikhail Gorbachev allowed them to return from exile to Moscow, which was regarded in the world as an important milestone in the cessation of the struggle against dissent in the USSR. "

Sakharov died on 14 December 1989 at the age of only 68, and in light of this it becomes obvious: for the broad masses of the population of what we today call the post-Soviet space, in particular in Abkhazia and Georgia, he became truly known only in the last six months. own life. It was those fateful months that included his speeches in May-June at the first Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR, when he, who seemed outwardly a feeble old man, unbendingly stood on the podium under the roar, banging, clapping and whistling of the “aggressively obedient majority” of the Congress, and a sensational interview published in Ogonjok magazine in October ...

In Abkhazia, both republican television channels devoted large reports to his centenary, and Abkhazian television began with footage shot on one of the central streets of Sukhum, which has carried the name of Academician Sakharov for almost thirty years.

The famous Abkhazian historian and political figure Stanislav Lakoba told Echo of the Caucasus today about his meeting with Andrei Sakharov, which took place in Moscow at the first, constituent congress of the Memorial Society in January 1989:

“As far as I remember, there were three delegates from Abkhazia. They were Iolanta Otyrba, Aida Grigorievna Ashkharua and me. Everything happened in the Moscow Aviation Institute, in the MAI club. One of the hosts of this event was Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov. There were a lot of people. And there I was given the floor to speak about what happened during this period in Abkhazia; I mean the 30-50s. Well, and then a conversation with Andrei Dmitrievich took place right there on the stage. That is, he got up, walked over and began to ask me about Abkhazia, in quite such detail: in general what is happening and how? Maybe for about seven minutes there was a conversation - directly, so to speak, in public. Then he asked me: ‘Have you heard, do you know about the case of the Abkhazian youths?’ I say: ‘What, was it actually called that?’ — ‘Yes, it was called that.’ I said that I suppose so, but as to which young men were being spoken of, apparently about such and such. And he agreed it was so. And he looked into the hall where Elena Bonner was sitting. And after some time they brought ... I was presented with archival documents about the rehabilitation of children by the name of Lakoba. Well, I mean the son of Nestor Lakoba, Rauf Lakoba, the son of Mikhail Lakoba, Nestor's brother, Nikolai. And Tengiz Lakoba is Vasiliy Lakoba's son. And the fourth is Koka Inal-ipa, the lad who was shot in 1941. Well, they were arrested in the course of the years [19]37-39.”

These archival documents, which he received from Sakharov, Stanislav Lakoba then quoted more than once in his publications about the Stalinist-Beriaite repressions in Abkhazia. He says:

“I used them when my book, Essays on the Political History of Abkhazia, was published. This was in 1990. I dedicated this book to ‘the blessed memory of Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov’. He was no longer alive. And just then, when our conversation took place at the Moscow Aviation Institute, I said that I had with me a copy of the so-called Abkhazian Letter [a document that had been sent to the Kremlin in 1988 setting out the history of Abkhazian dissatisfaction with their treatment over decades at the hand of the Georgian authorities -- editor] and I ‘would like to present it to you so that you are aware of the events’. He received this Letter with great interest. Thus, it actually then so happened that in the 31st issue of the Ogonjok magazine there was his interview, where he speaks of the Georgian SSR as a small empire."

Earlier, when in 1979 Andrei Dmitievich visited Abkhazia, Stanislav Lakoba spoke with his friend who were with him:

“Before that, I had already seen Sakharov. He came to Abkhazia and was here at the same time with a group of people ... It was in the summer or autumn of 1979. The last was his visit to Abkhazia, after which he was exiled to Gorky. Fazil Iskander was here then, as was also the writer Lev Kopelev, who was very friendly with Fazil, and Raisa Orlova, his wife. They arrived with Sakharov. They stayed in the hotel Abkhazia. I remember well how they sometimes went out to the coffee-shop opposite the hotel Abkhazia, where there was a so-called brekhalovka, the old one, and drank a cup of coffee. Then they visited the Nartaa restaurant, where they ate khachapuri (the boat-type they serve there) ... I think that Sakharov had an interest in Abkhazia through Iskander. As a writer, he greatly respected Fazil. He liked Fazil's works very much. At that time the first chapters of the novel Sandro from Chegem had already appeared.”

Just two days before his sudden death, Sakharov addresses the Soviet legislature on December 12, 1989. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev can be seen in the background.

To mark the centenary of Sakharov, a monument to him was unveiled in the city of Sarov, Nizhniy Novgorod region. Russian writer Viktor Erofeev dedicated a publication to him, which begins with the words:

“Andrei Sakharov is a bright personality. A thousand years will pass, and this is how, in my opinion, he will remain in the memory of Russia. Along with the saints. His life-evolution is a striving for precisely this canon”.

But in general, Sakharov's jubilee was held in Russia rather modestly, which is not surprising, given the strength of neo-Stalinism there today.

Even less surprising is the fact that in Georgia they completely preferred to observe this date in silence. Still: how can one fail to recall what effect, a veritable explosive informational hydrogen bomb, was produced in 1989 by only a few lines from his aforementioned interview entitled Degree of Freedom, given to the most popular journalist of Ogonjok in those years, Grigory Tsitrinjak. Here is the phrase: "This is the only way to solve national problems in small empires, which are essentially the union-republics, for example Georgia, which includes Abkhazia, Ossetia and other national entities."

Stanislav Lakoba recalls:

“There was a lot of noise then. There was a lot of dirt poured on him. I remember: Gamsakhurdia spoke very harshly, as well as many others."

Indeed, only the lazy in the Georgian society at that time did not react critically to these words, although there was nothing offensive in them in relation to the Georgian people — Sakharov talked about the matrjoshka-system of national state-formation generally accepted in the Union. Media-responses ranged from the indignant to the regretful that the great scientist and human rights’ activist had taken on something "which he doesn't understand”, or that, supposedly, he was misinformed ... Moreover, the professor of legal law Samuel Fleishman recently wrote:

“On the Internet, I have often come across a common false story, apparently born in the depths of Georgian propaganda, to the effect that, allegedly, academician Sakharov never said that Georgia is a small empire — allegedly some nameless journalist asked him a question, and the academician, not hearing him, nodded his head affirmatively. And then, allegedly in some newspapers, Sakharov offered refutations and apologies!"

This interview was published by Ekho Kavkaza, and is translated from Russian.