Stanislav Lakoba: "If Yeltsin had been opposed, the war in Abkhazia would not have started"

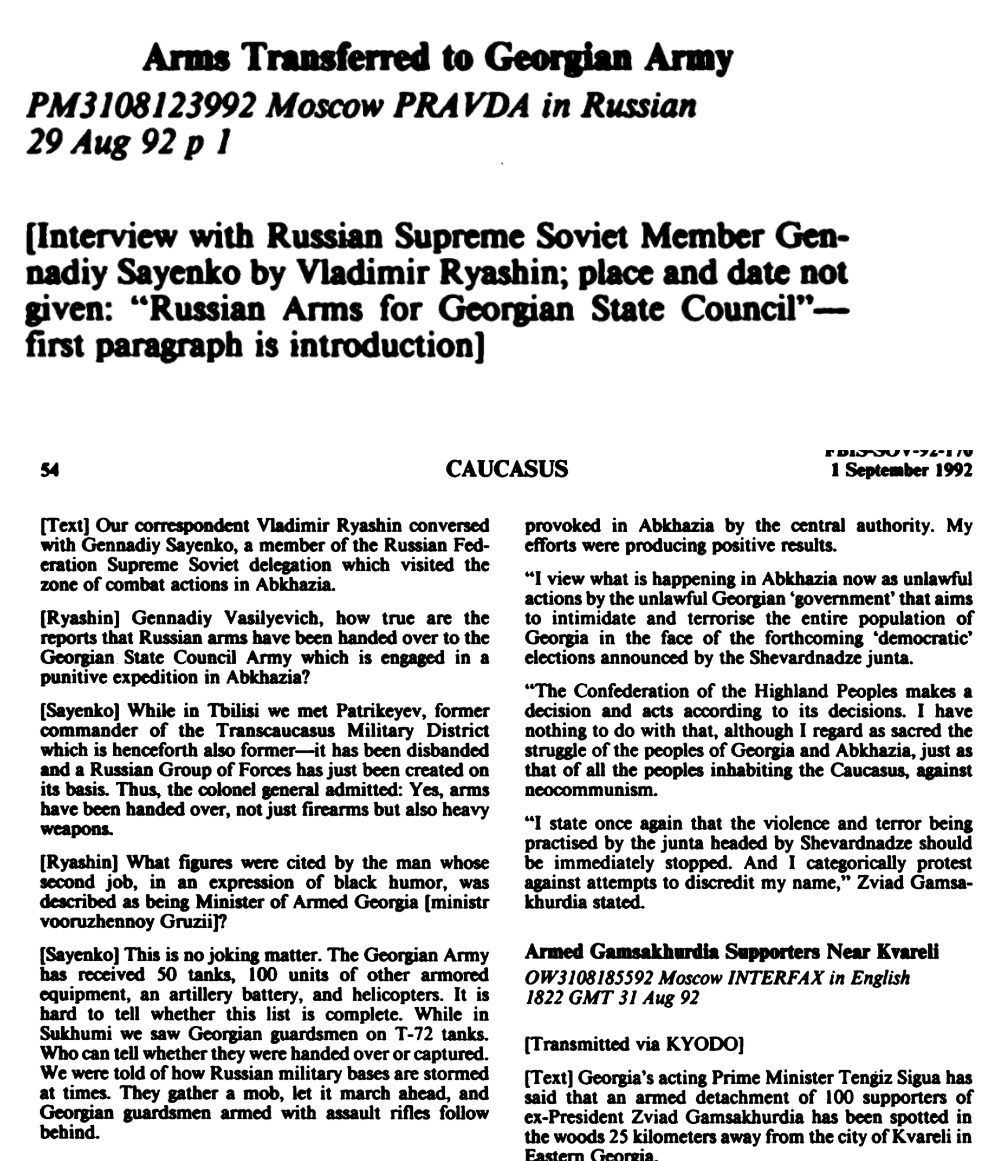

Russian President Boris Yeltsin welcomes Georgian Governing Council leader Eduard Shevardnadze. (June 24, 1992).

Ekho Kavkaza -- Stanislav Lakoba, Professor of History, author of the book “Abkhazia - de facto or Georgia - de jure?”, published in 2001 in Japan (Sapporo), which speaks about the Georgian-Abkhazian war of 1992-1993, a former Deputy of the Supreme Council and Parliament of Abkhazia (from 1991 to 1996), First Deputy Chairman of the Supreme Council, who twice served as Secretary of the Security Council (from 2005 to 2009 and from 2011 to 2013). During the war, he was a Deputy and headed the Commission on International Affairs and Inter-parliamentary Relations.

I look at the world from under the table,

The twentieth century is an extraordinary century.

The century is more interesting for the historian,

So much sadder for a contemporary.

— Nikolaj Glazkov

Elena Zavodskaja: Stanislav, you were a participant in many political processes that took place during the Georgian-Abkhazian war of 1992-1993, an eyewitness to many events. Your opinion and your assessment of the role of those political leaders who acted at that time are very interesting. Let's recall this and maybe start with the role of Boris Yeltsin. If Yeltsin had been opposed, the war in Abkhazia would not have started. This was a very controversial figure, especially if we talk about 1992, when Shevardnadze came to power in early March, and immediately after his appearance more than 30 countries recognised Georgia.

Stanislav Lakoba: Of course, considering this period, first of all, we need to talk about Yeltsin. If Yeltsin had been opposed, the war in Abkhazia would not have started. To me, this is completely obvious. This was a very controversial figure, especially if we talk about 1992, when, after Gamsakhurdia, Shevardnadze came to power as a result of a coup in early March, and immediately after his appearance more than 30 countries recognised Georgia. Under Gamsakhurdia, this was not the case. By and large, Gamsakhurdia met the interests of Russia more than Shevardnadze, but circumstances developed precisely in this way. Gamsakhurdia himself was already saying openly at that time that it was a conspiracy, primarily by the Americans, that Secretary of State Baker and [Pres.] Bush took part in his overthrow. And without the participation of the military, nothing would have happened. We know, that at that time Grachev (later the Minister of Defence of the Russian Federation) was actively in contact with Kitovani. Kitovani led Georgia’s "National Guard" and then went against Gamsakhurdia. At one point, Baker stated that Russia's policy in that period (until 1994) was carried out in the wake of American foreign policy.

On 24 June 1992, a meeting was held in Dagomys to resolve the South Ossetian conflict, which had begun under Gamsakhurdia. Shevardnadze wanted to wash his hands of the affair because he was against this conflict, and there were completely different issues on the agenda – it was necessary to join international organisations. At the Dagomys meeting on 24 June, an end was put to the war, the parties agreeing that it would be stopped. And it had to be stopped, because without the voice of Russia and in the presence of hostilities, Georgia could not become a member of the UN. The agreement was signed, and on the same evening a communiqué was signed between Yeltsin and Shevardnadze that they would cooperate, i.e. their law-enforcement agencies in the territories under their jurisdiction would fight against semi-legal and other armed groups, which later led to the fact that that on 14 August Georgia brought its troops into the territory of Abkhazia. This meeting in Dagomys went down in history as the “Dagomys Conspiracy”. In fact, the green light was given for military action. The fate of Abkhazia was predetermined.

E.Z. Why?

S.L: Because an agreement was signed - a communiqué - that they would restore order: there were Georgian troops in Georgia, and Russia would not interfere. That's what it was all about.

E.Z: Stanislav, in your opinion, what strategic goal did Yeltsin pursue in relations with Georgia and Abkhazia at that time?

S.L: During this period, Yeltsin had very vague, as it seems to me, ideas about what would be and how it would be. Interestingly, foreign policy issues, especially in the Near Abroad, in Transcaucasia, at that time were dealt with to a greater extent by the military department than by the diplomatic one, and this was confirmed by events.

The main goal of the then leadership of Russia and Yeltsin was to get Shevardnadze, even before he came to Georgia instead of Gamsakhurdia, to agree that he would join the CIS. But as soon as Shevardnadze was in Georgia, he began to behave in a completely different way: he forgot about his obligations, delayed their fulfilment, said that the Georgians were weak, that they were now fighting the Zviadists, that we needed to strengthen the army, put things in order, that they had no weapons and might be overthrown and the restoration of the Gamsakhurdia regime might take place. He seemed to frighten Yeltsin with this and even staged a performance in Tbilisi with the seizure the television-centre. It happened on 24 June – during that day Shevardnadze finished fighting this coup then suddenly declared: "The game is over!" And in the evening he flew to meet with Yeltsin. Apparently he convinced him, despite the fact that Georgia was not yet a member of the CIS, to supply weapons.

Yeltsin gave Shevardnadze everything he wanted: both weapons and the Transcaucasian Military District supported him, and they organised an off-loading [sc. of troops & equipment], but Shevardnadze could not take advantage of this.

E.Z.: Yes, it is known that on the eve of the war weapons which were available at Soviet military bases in Georgia were handed over to the Georgian leadership. Tell us a little more about what weapons were discussed and how this transfer took place?

S.L.: Several divisions, tanks, armoured vehicles, planes, helicopters were transferred. I can’t name the exact number, but there were a lot of armoured vehicles. Shevardnadze addressed the State Council on 11 August and said: "We are as strong as we have never been, even two or three days ago." There are relevant publications by serious analysts who wrote that this happened in late July - early August. In particular, there was a huge base in Akhalkalaki – its weapons were transferred, then the entire Transcaucasian district was actually subordinated to Shevardnadze. And we know that on the armoured vehicles that entered Abkhazia on 14 August it was mainly the servicemen of the Transcaucasian Military District who were serving as mechanics and drivers.

The Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) archive.

See also: Russian Officer Views Abkhaz Conflict (27 April 1993)

E.Z: You write that Yeltsin supported Georgia until 25 September 1992. This was the day when Shevardnadze suddenly turned to the West for help at a meeting of the UN General Assembly in New York and laid the blame on Russia. What happened between Yeltsin and Shevardnadze in September 1992? What was the basis of the change in relations, or were they shaky from the start?

S.L.: To speak briefly, it must be said that there was a first stage – let’s consider it as such from the Dagomys communiqué of 24 June 1992 to the end of September 1992. At this stage, Yeltsin and his entourage supported Georgia, because Shevardnadze assured them that there would be a blitzkrieg – a lightning-war that would end in two or three days with little bloodshed, that they would simply change something here, remove a few people, and then they would meet on Sunday at Krasnaja Poljana. On the 16th, in Krasnaja Poljana, on the territory of the military sanatorium, tables were laid, and Yeltsin was present in Sochi.

Moreover, he had come to Krasnaja Poljana that day, but his escort-cars turned around and left, because the blitzkrieg had not taken place. Yeltsin gave Shevardnadze everything he wanted: both the weapons, and the Transcaucasian Military District supported him, and they organised an off-loading, but Shevardnadze could not take advantage of this. He underestimated, apparently, the Abkhazian capabilities, thinking that at the sight of armoured vehicles everyone would scatter, and no-one expected that clashes would begin. Moreover, the operation itself misfired. They planned to land early in the morning directly from the railway platforms, starting from the border at Leselidze (in Gjachrypsh and Tsandrypsh), and the units were to de-train along with armoured vehicles in such a way that the whole country would in effect be occupied by the military in the morning.

But unexpectedly for everyone, one of the bridges on the approach to the River Ingur exploded, so that the tanks had to be reloaded from the platforms; they made their own way and only reached Sukhum during the day. The first skirmishes began already on the 14th, and a tank was knocked out at the turn-off to Tkvarchal.

During this first period, when several divisions with weapons and armoured vehicles, helicopters, planes, etc., were transferred to Georgia, Yeltsin did a lot: he closed his eyes and lent support.

By the way, Georgia was admitted to the UN on 31 July, and two weeks later the war began. Moreover, Chikvaidze, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, speaking at the United Nations, said that there was no non-Georgian land in Georgia, and that they would defend their land to the last inch. That's what he said on the eve of the war. And when the setbacks began, Shevardnadze suddenly appeared in New York and began to accuse Russia of “being in the way and pushing us together, preventing us from living in peace”, and so on. Yeltsin also had an opposition parliament and serious opposition within the country. And everyone began to oppose him. No sooner had Shevardnadze left the UN rostrum than a resolution of the Supreme Council of Russia was adopted, which was called "On the situation in the North Caucasus in connection with the events in Abkhazia", in which they demanded the immediate withdrawal of Georgian troops from the territory of Abkhazia. Shevardnadze himself from New York immediately flew to Moscow, and he later said that Yeltsin met him extremely coldly.

On the eve of war Dzhaba Ioseliani told Shevardnadze: "We must sign with them on the CIS." And Shevardnadze answered him: "Don't rush. First, we need to deal with Abkhazia.”

E.Z.: That is, after Shevardnadze's speech at the UN, where he blamed Russia for the failures, did he then expect a warm welcome in Russia?

S.L.: I don’t think that he expected to be received especially warmly, but he probably didn’t think that there would be such a reaction, because a lot of things had been forgiven him. It was his blunder, of course. Yeltsin then said in a fit of temper: " God knows what he expected of himself, but under him there’s not even a banana republic." These are Yeltsin’s well-known words. After all what I’m saying is that everything revolved around the CIS. Then Grachev became convinced that his friend Kitovani and others could not resolve the issue of Georgia's entry into the CIS, and this was the main issue. Moreover, they convinced themselves that they were not thinking and would not even have thoughts about this, and then, lo!, the situation escalated.

Yeltsin also understood that there could be no question of Georgia joining the CIS. It is very interesting here that on the eve of the war, Dzhaba Ioseliani told Shevardnadze: "We must sign with them with regard to the CIS." And Shevardnadze answered him: "Don't rush." And then Dzhaba – he was a wit – says: “Listen, if they sneeze in Moscow, we will have bilateral pneumonia!” To which Shevardnadze objected: “First, we need to deal with Abkhazia.” This was on the eve of the outbreak of hostilities. To put it graphically, Shevardnadze wanted to enter Abkhazia without entering the CIS. He was playing his own game.

Boris Yeltsin with the head of the Georgian state, Eduard Shevardnadze, and the founder of the Mkhedrioni paramilitary organisation, Jaba Ioseliani (1994).

S.L.: It was a Western game, but it was engineered by the hands of the Russia of Yeltsin and some people from his entourage. However, in Russia there were forces that were opposed and which supported Abkhazia – that very Parliament, the peoples of the North Caucasus, the Cossacks, Southern Russia – there were a lot of volunteers who came to Abkhazia.

E.Z: What was the essence of this game by Shevardnadze, please clarify?

S.L.: In the United States in early February 1992, Shevardnadze, by a decision taken behind the international scenes, not being the leader of Georgia (he arrived in Tbilisi only on 7 March 1992 and became a member of the State Council), signed a protocol with the company Brock Group LTD on Georgia’s economic geo-strategy for the coming decades. I have published these materials. They needed a man like Shevardnadze.

E.Z.: What was it about?

S.L.: It was about the transportation of energy-resources, about the seaports – Batumi, Poti. There were plans, sketches of the future Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil-pipeline by-passing Russia. That’s to say, in efffect, he was given the green light for all this there, in America, in February 1992.

E.Z.: Please specify where Shevardnadze led Georgia, in what direction, what was the goal?

S.L.: Shevardnadze took Georgia out of Russia's influence, he was not going to join the CIS and took a direct course towards the West. But at that moment, he couldn't do it. He relied too much on his Western friends.

As a result of this war, on 9 October Georgia joined the CIS, because otherwise Shevardnadze would have been removed and Gamsakhurdia would have been installed. Moreover, Gamsakhurdia was in Mingrelia; there were battles in Poti. Then do you remember what happened when the Russian marines landed? They helped Shevardnadze and unblocked the railway to Poti, Samtredia, the ports, etc. Those were the agreements. And then suddenly there was a meeting in Moscow, where on 9 October 1993 Shevardnadze, after losing Abkhazia, signed a document on joining the CIS.

That's why former Defence Minister Sharashenidze criticised him, saying that there had been an opportunity to do it earlier, and everything would have been fine, and there would have been no war in Abkhazia, and nothing at all. Moreover, they provided, it seems, for 20 years territories for Russian military bases in Georgia; the port of Poti was transferred to Russia, and some personnel (Giorgadze, Nadibaidze), in whom the Russian Federation was interested, were sent back there. And Shevardnadze for a time, until about 1996, again returned to the orbit of Russian influence.

Those days there was a real genocide. Even the Minister of Internal Affairs of Georgia, Lominadze, recalled: “The Kitovani guards attacked the city like locusts. I never thought we were so shameless."

E.Z.: Stanislav, you’ve covered the role of Yeltsin and Shevardnadze. Let's move on to the role of Vladislav Ardzinba. In the military situation, when hostilities had already begun in Abkhazia, what kind of relations, what points of tension existed between the three leaders? Describe Vladislav Ardzinba, his views on the situation and behaviour?

S.L.: Of course, he still counted on the fact that Russia and Yeltsin, with whom he’d had a meeting the day before, would not be indifferent, that they would provide some kind of support. On the first day of the war, the 14 August, he tried to contact Yeltsin, who was in Sochi, but Korzhakov answered him several times: "Boris Nikolaevich is at sea ...". In fact, there were no contacts. We saw the Russian military evacuate in a hurry.

Of course, Vladislav Ardzinba was somewhat confused, but he did not lose his presence of mind. It is very important that on 14 August he made a statement on Abkhazian television and called on the people to resist, saying that this was an act of aggression. This is very important, because on that day it was extremely difficult to find one’s orientation. Moreover, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation turned to the leadership of Georgia and supported what was happening. This was under Kozyrev, as was published, by the way, on 19 August 1992 in Free Georgia. They supported this action, saying that it was a fight against separatists, terrorists, etc. Do you know what was happening here and what was being done to the multinational Russian-speaking population, what happened with the Armenians, Greeks, not to mention the Abkhazians? There was a real genocide here those days. Even Georgian Interior Minister Lominadze recalled: “The Kitovani guards attacked the city like locusts. I never thought we were so shameless." Thus did he speak after the war and said: "We are guilty of many things."

Tengiz Kitovani, Minister of Defence of Georgia in Sukhum, Abkhazia (August 15, 1992).

E.Z.: In those difficult days, what mood was Vladislav Ardzinba in? How did he, not only as a historical figure, but as a person, react to the situation?

S.L.: What happened was a big surprise for him. It was felt that he was feverishly trying to do something, to get information, to contact the top man by phone. Was it a coincidence that he tried to contact the leader of Russia? It was obvious that, if Yeltsin had been against it, there would have been no military adventure. There was a conspiracy, and we can talk about it now that we are familiar with the documents and materials.

Yes, a certain group of Deputies was nearby then, but for security reasons he was not available. We understood that people were looking for him, it being said openly that "the issue needs to be resolved with Ardzinba". Then it became known from some sources that one of the TU-134 planes from Tbilisi was at the airport in Adler with Georgian special forces. They apparently had the idea that the leadership of Abkhazia would make a run for it, and that they would seize everyone at the border, put them on a plane and take them to Tbilisi, including the Deputies.

+ Georgian-Abkhaz War | FBIS Reports (Aug-Oct. 1992)

+ 'Absence of Will': A commentary

+ The TV Debate Program on Georgian - Abkhaz Conflict | Moscow, October 17, 1992

Georgian president Eduard Shevardnadze stands with soldiers at the parliament building. September, 1993. Sukhum, Abkhazia.

Then there was an amphibious landing from the side of the border with Russia to cut us off from the Russian border. And only on the 17th die we see Vladislav in Gudauta. That’s to say that those days there was no contact– he was with his guards.

It is very important, our deputies also remember that on the 17th in Gudauta, Vladislav's guard Vitalij Bganba called him to the phone – there was a high-frequency telephone in the car – this was the first call from Moscow, Burbulis called, he was then Secretary of State. In the evening Vladislav appeared and was already in a completely different mood.

E.Z.: How did his mood change during those days?

S.L.: Every day Ardzinba’s mood became more and more definite; he spoke in Gudauta, it seems, on the 17th, from the balcony and called on the people to resist. A significant role in this was played by Pavel Kharitonovich Ardzinba, who was recently killed as a result of a terrorist attack.

He stood nearby, he had the means thanks to which they began to acquire weapons and uniforms. Valerij Aiba was also next to him. These people formed the backbone of the resistance. Deputies, of course, too, but not all, about 14 of them. These are those who stood nearby, supported, cemented the situation. As for the rest, sometimes it was not clear what role they played.

Then Vladislav began to gain strength. It was very difficult to endure this situation: the death of people, the tragedy, the displacement of the population, it was necessary to organise conditions for the life of the refugees who managed to get out of the occupied part of Abkhazia. Contacts with various political forces in Russia did not stop. We have to pay tribute – everyone - liberals, democrats, nationalists - all supported Abkhazia. For example, Elena Bonner and Deputy Starovoitova gave support. They knew Abkhazia, understood what was happening. They said: “If Russia has let you go, you let Abkhazia go. After all, Georgians, what are you doing?”

Of course, Yeltsin and Russian policy were strongly influenced by the rising of the North Caucasus. They saw that the security of the Russian Federation itself was in question. I mean the volunteer-movement in support of Abkhazia, the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus, it made such a serious impression that Yeltsin and others were forced to correct their course.

The Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) archive.

After all, this is how they thought: “We’ll quietly, silently slam Abkhazia, we’ll come to agreement with Georgia, Shevardnadze is still our man, he worked in Moscow, Gamsakhurdia is not our man, and if we have Shevardnadze, we’ll have the entire former Georgian SSR, including Abkhazia.”

They didn't want any problems, and, it seems to me, they talked very freely on this topic, but in many ways they didn't even understand the subject they were talking about. Such was my impression.

But there were people who understood, for example, Sergej Nikolaevich Baburin, who knew and studied our problem. There were others; Deputies came, and not only Deputies. Returning to Vladislav, I want to say that he behaved very resolutely and firmly, showing considerable perseverance. No-one could have been a leader like him during that period. We must give him his due – he behaved very courageously, and as a historian he understood the role he played. In fact, Ardzinba did the impossible during that period.

Before the war Ardzinba said: “If necessary, I will even come to Tbilisi and talk there.” But Shevardnadze did not react, he simply wanted to destroy, humiliate, trample...

In his memoirs, General Levan Sharashenidze, the former Minister of Defence of Georgia, directly writes that Shevardnadze is solely responsible for starting the war. Before the war, in the month of May, he had a meeting with Ardzinba, and Ardzinba said: “If necessary, I will even come to Tbilisi and talk there.” He says: "I reported all this to Shevardnadze." But Shevardnadze did not react, he simply wanted to destroy, humiliate, trample... That's what he thought.

E.Z.: Speaking about the pre-war and military situation, one cannot speak about Zviad Gamsakhurdia. Stanislav, please tell us about the role he played in the situation, did his views change and how?

S.L.: At first, he made extremely chauvinistic statements about many peoples who lived on the territory of the former Georgian SSR. At the beginning of 1989, there was his appeal "To the Georgians in North-Western Georgia", where he spoke out against the Abkhazians, saying that they were supposedly immigrants, with no connection to Abkhazia. He even urged Georgians not to attend Abkhazian funerals and weddings. There were such petty things in 1989, but little is said about it, and yet, after all, this was the start of 1989, and, by the way, it all made a depressing impression not only on the Abkhazian population but on the entire non-Georgian population in Abkhazia, and even on those Georgians [recte Kartvelians – Trans.] who lived here. Such statements led to the events of April 1989 in Lykhny, where many thousands of people gathered, at which the question of restoring the status of the Abkhazian Republic of 1921 was raised.

+ Zviad Gamsakhurdia: “Abkhaz Nation Doesn’t Exist!”

+ The Guardian: Georgia elects ultra-nationalist (April 15, 1991)

+ The Guardian: Zviad Gamsakhurdia - Georgian rebel turned dictator (January 4, 1994)

Gamsakhurdia followed this line until about March 1991, when the referendum took place. After the referendum, an air-assault battalion was transferred to Abkhazia, plus the Confederation of the Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus was operating, and he saw that a colossal threat had arisen here. At that time, he was already fighting in South Ossetia and, apparently, realised that he could not fight on two fronts. And then he suddenly spoke in a completely different way: he said that the Abkhazians are the same indigenous people as the Georgians; he began to talk about bi-aboriginalism, and even about the need to form a parliament. Gamsakhurdia even proposed quotas based on ethnicity, although he was offered, in particular by the Abkhazian lawyer Zurab Achba, a bicameral parliament: a chamber of nationalities and a chamber of the republic, where all national communities would be represented. But he didn't like it, saying that it would be a very dangerous tool for Georgia itself: if a bicameral parliament were created, then large groups of people living in Georgia, for example, Armenians and Azerbaijanis, might cause a lot of trouble for the parliament. He proposed ethnic quotas, i.e. 28 deputies to be Abkhazians, 26 to be Georgians [recte Kartvelians – Trans.] and 11 to be Russophones. Moreover, he went even further and began to say that it would be nice to create an Abkhaz-Georgian federation by analogy with Czechoslovakia. In principle, as I understand it, he began to move away from the brink and realised that a bad peace is better than war. 26 are Georgians and 11 are Russian speakers. Moreover, he went even further and began to say that it would be nice to create an Abkhaz-Georgian federation by analogy with Czechoslovakia. In principle, as I understand it, he began to move away from the brink and realized that a bad peace is better than war. 26 are Georgians and 11 are Russian speakers. Moreover, he went even further and began to say that it would be nice to create an Abkhaz-Georgian federation by analogy with Czechoslovakia. In principle, as I understand it, he began to move away from the brink and realized that a bad peace is better than war.

E.Z.: There is such a point of view in publications that it was not Shevardnadze who initiated the sending of troops into the territory of Abkhazia on 14 August 1992. What do you think about this?

S.L.: In such a sense – the opinion of the former Minister of Defence Levan Sharashenidze is very interesting, who writes that from February to May 1992 he had many meetings with Ardzinba, and Ardzinba agreed to negotiate with Shevardnadze, but Shevardnadze was to blame, because he made no concessions.

Shevardnadze was determined to solve the problem by force. When surrounded by the likes of Kitovani and Ioseliani, he did not have much room for manoeuvre.

E.Z: And why did he not agree to a meeting with Ardzinba, what do you think?

S.L .: Because Shevardnadze was determined to solve the problem by force.

When surrounded by the likes of Kitovani and Ioseliani, he did not have much room for manoeuvre. But the opinion that Shevardnadze was allegedly against the introduction of troops, whilst others insisted on it, does not hold water. Read, for example, how on 11 August Shevardnadze spoke at the State Council. He said that they would bring order to the entire territory of Georgia, starting from Leselidze, and that their borders were inviolable.

E.Z.: Before the war, many had the idea that Shevardnadze was smart enough, experienced enough and diplomatic enough not to start this war. And now you are saying that he expected to destroy and conquer Abkhazia by blitzkrieg. Why did he underestimate the possible resistance?

S.L.: I'm not saying that – it's about documents and materials. Indeed, he wanted to solve the problem in Abkhazia quickly in this way. They took Mingrelia as their example, where they entered and everyone fled. They killed people, mocked them, and probably thought that the same thing would happen in Abkhazia. But here everything turned out differently.

Throughout his life and career, Shevardnadze had Abkhazia as a sui generis "obsession". He began all meetings with the question: “How is it there in Abkhazia?” And he was always very fearful. Of course, everything could have been decided differently. Even Levan Sharashenidze writes that he was surprised how this man, who led the Russian Foreign Ministry, with a wealth of experience, could not find a common language with Ardzinba and Abkhazia for five or six months. Nevertheless, Shevardnadze did not take a single step forward.

By the way, the Georgian historian Zurab Papaskiri also writes that it is surprising how Shevardnadze, a person with such experience, could do this. He should even have gone to Sukhum and negotiate with Ardzinba, find out what the Abkhazians wanted and what they wanted. This only confirms what Sharashenidze wrote about. Apparently, the goal was completely different; he wanted to solve this problem by military means, to cut the Gordian knot at once, so as not to make a fool of himself with these Abkhazians. For me, this is completely obvious.

Ioseliani said something very interesting: “I warned them later: Don’t do this. I know the Abkhazians. What do you think? – You’ve been given tanks and planes, and you’ll be able to roll over over them, the Abkhazians? I’ve sat with them, I know them, they will turn you over."

But he did it mainly through the agency of Kitovani. I spoke with Ioseliani in Geneva during the negotiation-process in 1994. I asked him: "Dzhaba, how did this happen?" He answered me: “You know, I was generally against it. This is Shevardnadze and Kitovani.” I say to him: "How?" And he says that they decided this on the 11th at a meeting of the State Council, at which he was not even present. And it's true, he wasn't there. And he even said such a very interesting thing to me: “I warned them later: Don’t do this. I know the Abkhazians. What do you think? – You’ve been given tanks and planes, and you will be able to roll over them, the Abkhazians? I’ve sat with them, I know them, they will turn you over.” Here are his words verbatim. And then he interestingly finished his monologue: “They will turn you over”, paused and said: “So, that’s what we got.” I say: “Are you then not involved in these cases?” “I,” says Ioseliani, “was involved, but only later.” I say to him: “Well, what were you doing in the Ochamchira Region?” And he replied: “Well, I can’t answer for every scoundrel, you also have scoundrels.”

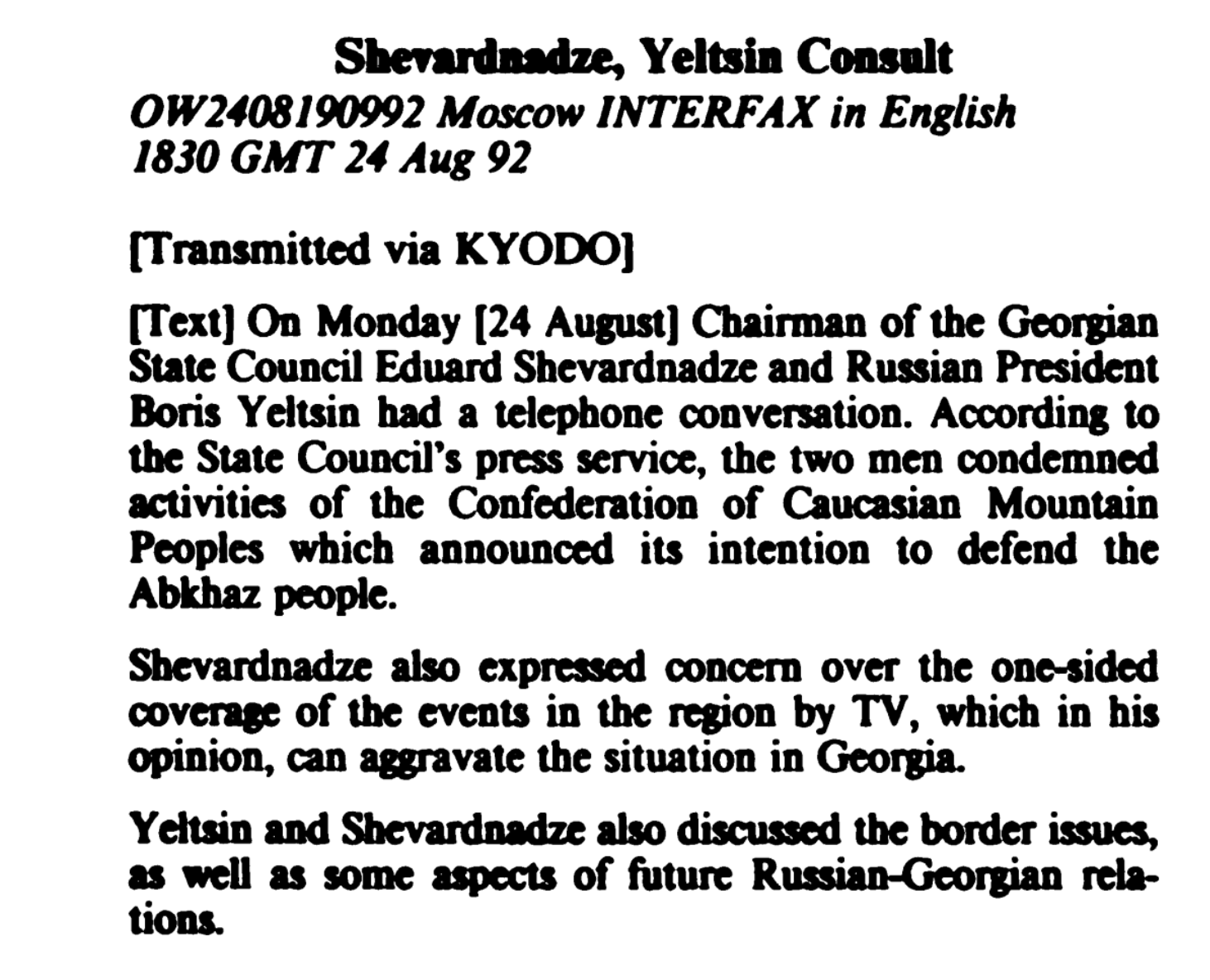

E.Z.: How did the relationship develop after the outbreak of hostilities between Vladislav Grigorevich Ardzinba and Boris Nikolaevich Yeltsin? We all remember the footage in the news when Yeltsin, Ardzinba and Shevardnadze go out to the reporters and such a strange situation arises when Yeltsin tries to force Ardzinba and Shevardnadze to shake hands. These seconds give the impression of being very tense and very tragic. Can you somehow comment on that situation?

S.L.: I was talking about what happened on 25 September. Shevardnadze went to the States and made accusations against Russia there. After that, there was a complete reversal in Russian politics. Already in early October, Gagra was liberated and the border with Russia was opened. And on 3 September, the question of war and peace, the future of Abkhazia, was being decided in Moscow.

This meeting was attended by representatives of many republics of the North Caucasus, and it was decided that this conflict could be resolved politically and diplomatically. First, as I understand it, one document was presented, which was discussed on our part, and on the other hand, some comments were made, but it proved to be generally acceptable. And then, as Vladislav Grigorevich himself said, there was a short break, Yeltsin and Shevardnadze retired, went out together. Then Yeltsin appeared, obviously drunk, and said: "We will not sign that document, let's sign another document." Ardzinba tells him: “We need to have a discussion, Boris Nikolaevich; how are we going to sign it without looking at it?” “No,” Yeltsin told him, “we must sign, we don’t have time now to discuss every point.” And there was this situation: if the Abkhazian side had not signed that document, it would have meant that we were against a peaceful settlement, against everything. Anything at all could have been forced on us. And there were people, as he said, who, both to the right and to the left, told him: “Sign, sign, sign.”

Ardzinba was forced to sign that document. It was about the territorial integrity of Georgia, about the fact that not all troops would be withdrawn, and Georgia would leave part of its military on the territory of Abkhazia. And there was no longer a word about the federal structure of Georgia.

Parliament delegated Vladislav Ardzinba and Yuri Voronov to this meeting. And so there was a situation that Ardzinba was forced to sign that document. It was about the territorial integrity of Georgia, about the fact that not all troops would be withdrawn, and Georgia would leave part of its military on the territory of Abkhazia. And there was no longer a word about the federal structure of Georgia. And what you are talking about is very important: when they went out to the journalists, Ardzinba behaved in an outstanding way. He actually disavowed this document when he said that “the hope is in you, Boris Nikolaevich, we signed this document out of respect for you, we were forced to sign it” – he did even say this! And then he did not want to give Shevardnadze his hand, as you remember, although hands were, nevertheless Vladislav still did not offer his hand. And you can see what a grin Shevardnadze had, whereas he [Ardzinba] was furious. Nobody expected that Vladislav would conduct himself in this way. Take any politician, I think no-one could behave like that in that situation. I believe that this was a turning point, after which Yeltsin somehow looked at him differently.

Vladislav Ardzinba, Boris Yeltsin and Eduard Shevardnadze (September 3, 1992).

E.Z.: And what brought about such a revolution in relation to Abkhazia after this meeting and the speech of Vladislav Ardzinba? Is it the will to resist or what? As a historian, please be specific.

S.L.: In short, what was it that became clear to many there? “They twist my arms, but we do not give up, we will continue!” That's what it meant. And everyone understood what state he was in, understood that in effect he alone stood in opposition to the whole world. Vladislav later told me that after that all doors were opened for him, all his questions were solved by the head of the government Yegor Gaidar. This refers to humanitarian aid, food and other matters. “There were a lot of problems, and he removed these problems. There was no occasion where I came and had to stand somewhere in the waiting room, being kept waiting,” said Ardzinba.

E.Z.: Since we are covering the international context of the Georgian-Abkhazian war, please tell us about the role of the two leading Georgian security officials - Kitovani and Ioseliani.

S.L.: This is what one person (I won't name him) told me who came to Tbilisi after the events in January 1992, when Gamsakhurdia was expelled. So, when he arrived in Tbilisi, he was met by Dzhaba Ioseliani. And when Ioseliani was driving with him in the car, he said to him: “Do you know what they say in Tbilisi about me and Kitovani?” He replied, “No, I don't know. What do they say?” “They say,” Ioseliani said, “that a well-known thief has come to power - this is me, and an unknown artist - this is Kitovani, he is a sculptor!”

Grachev thought that with the help of Kitovani it would be possible to formalise Georgia's union with the CIS. After all, it wasn’t just in a straightforward and disinterested way that he helped them with weapons.

Of course, they were different people. As far as I know, Ioseliani could not abide Kitovani. He once said about him: "This is an animal." He considered him a butcher, an uncouth, not subtle man. Ioseliani, of course, was more subtle, more intelligent. Of course, they were the driving force. Kitovani headed the former "National Guard" and was an ardent opponent of Gamsakhurdia; he was on close, friendly terms with Grachev. Grachev thought that with the help of Kitovani it would be possible to formalise Georgia's union with the CIS. After all, it wasn’t just in a straightforward and disinterested way that he helped them with weapons. And Ioseliani was a completely different kind of person.

Russian President Boris Yeltsin and Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze after signing the Treaty of Russian-Georgian Friendship, Good Neighborliness, and Cooperation. Behind Andrei Kozyrev and Jaba Ioseliani (February 3, 1994).

E.Z.: What kind?

S.L.: For example, Ioseliani believed that Georgia needed Shevardnadze, while Sigua and Kitovani were against his coming to Georgia. After Shevardnadze spoke with Kitovani for five hours in Moscow, Kitovani became different and changed his mind.

Ioseliani, when I asked him “Why did you need Shevy?”, he replied: “You know who we are? We need a screen." I told him: "You will destroy yourselves." But he still believed that they needed Shevardnadze as a screen, being known throughout the world. And nobody knew them. “You know,” he told me, “our biography.” This is how he talked about it. In part, it was a criminal power, and a criminal revolution that took place there. Gamsakhurdia, of course, was a person from a completely different environment, from an intelligent family, the son of a writer, but he was carried away by romantic nationalism. And then, when he faced reality, everything turned out to be different there, but, as it seems to me, he never abandoned national romanticism.

There were certain contacts with him, there was a moment when he wanted help from Abkhazia. Imagine, a man said that Abkhazians as such did not exist, and then suddenly he spoke in Abkhaz. He also made an appeal in the Abkhaz language in 1993, at the height of the war.

E.Z.: What was the sense of his conversion?

S.L.: He said that we are brothers, that we should help each other, that Shevardnadze is a usurper, etc. He was offered, as I understand it, a buffer-state within the frontiers of Mingrelia, but he wanted all of Georgia, but all Georgia, it seems, they did not intend to grant him. And when Shevardnadze understood what was going on, he gave the go-ahead both to join the CIS and to the presence of Russian bases, then he was given support, and he entered the CIS. Two years later, in 1996, Russian positions weakened, and he again broke out of this orbit. Do you remember there was an attempt on his life? Then they accused Giorgadze; then Giorgadze left; there was such a person as Nadibaidze, the Minister of Defence – these were considered pro-Russian. There was a struggle for spheres of influence...

This interview was published by Ekho Kavkaza on 21st October 2018, and is translated from Russian.