Abkhazia's archive: fire of war, ashes of history, by Thomas de Waal

The documented history of the cosmopolitan Black Sea territory of Abkhazia was destroyed in war on 22 October 1992. Its Greek archivist is conserving what little remains, reports Thomas de Waal.

(This article was first published on 20 October 2006)

12 - 07 – 2007

For me the tragic story of Abkhazia's archive is inseparable from the story of its archivist.

I first met Nikolai Ioannidi in May 1992 in Sukhumi, then capital of the autonomous republic of Abkhazia and still firmly part of Georgia. War was about to break out between the Abkhaz and the Georgians, but I sensed this only vaguely, noticing that there was a curfew at night, a dispute over which security forces had the right to bear arms and worried speculation from the people I spent my time with about the future.

I had a rather skewed view of this strange tense situation because all my companions happened to be Greek. I had chosen Abkhazia, pretty much at random, as a location to make a BBC radio feature about the plight of the Pontic Greeks, and the dilemma they were facing as the Soviet Union collapsed: should they abandon their ancient Black Sea habitat and emigrate to a strange country called Hellas?

I spent several days, living in a wooden hut by the Black Sea, being plied with too much cognac, touring villages, schools and cultural societies - and never for a moment freed from the hospitable guard of my Greek hosts. It felt as though I was the captive of some long-lost Greek domain from the Byzantine era.

One day they took me to see the archive and its remarkable Greek curator, Nikolai Ioannidi. He was tall, gaunt, with parchment-pale skin and keen blue eyes - from his German mother, it seemed, rather than his Greek father. He smoked a lot, talked clearly and exactly and wore a navy-blue beret. He was the great expert about the history of Abkhazia and about the Pontic Greeks of the Black Sea

As Ioannidi spun a fascinating tale about the history of Abkhazia's Greeks- their role in the 19th-century Russian-Ottoman wars, the fortunes they made in shipping and tobacco, their mass deportation by Stalin in 1949 and begrudged return a decade later - I barely noticed the archive we were sitting in, except to register that it was home to a unique collection of Pontic Greek newspapers.

Abkhazia had only three more months of peacetime existence. In August that year the Georgian army - or to be precise a collection of ragged armed looters nominally subordinate to the embryonic military forces of a new and barely functioning state - entered and sacked Sukhumi and ousted the Abkhaz authorities. War broke out. The Abkhaz were first driven north by the Georgians, then in the autumn of 1993, with Russian help, turned into vengeful victors, driving out the Georgians.

A history erased

It was ten years before I saw Sukhumi, the archive and Ioannidi again. In the meantime I had covered the war in Chechnya and the aftermath of conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, but had not been back to my first conflict zone in the Caucasus.

I could barely make sense of the geography of the place I visited. Although fighting had ended eight years before, grass was growing in the streets of Sukhumi and half the city was still in ruins. The vast burned hulk of the Abkhaz parliament loomed over the town, a blackened shipwreck beached in the middle of the central square. There was an air of Pompeii about it: the city's largest community, its Georgians, had fled in their entirety, leaving Sukhumi the half-empty capital of a new seperatist state, recognised by no one. The Abkhaz had won a "victory", but the price was impossibly high.

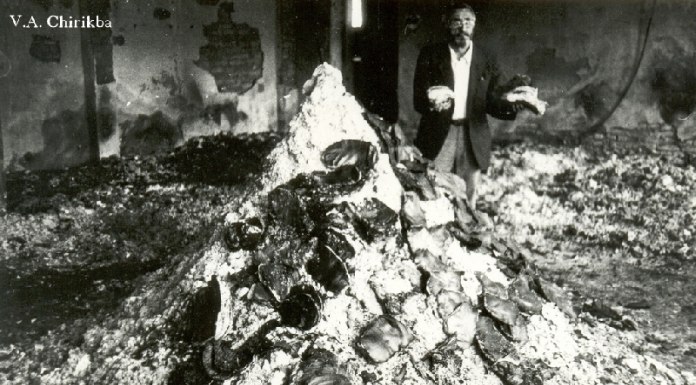

Instead of an archive there was a damp square of ground with the low black empty shell of a building - one wreck amongst many. Ioannidi now worked out of two corridors in the cold wing of the university, piled waist-deep with cardboard packages. He told me the story of what had happened.

Ioannidi lived in Sukhumi's "new town", a Soviet dormitory of tower-blocks two miles from the centre, where the archive was. On 22 October 1992, the city was under Georgian military control and curfew and he had made his precarious way home when it was still light, as the snipers were beginning their evening's work.

At 8pm a neighbour who lived next to the archive rang and said the building was on fire. There was no way Ioannidi could make his way back, so he had to wait until morning to find out what had happened during the night.

Late in the afternoon a car with five or six young Georgians wearing black uniforms of the Sukhumi military police had drawn up outside the archive. They broke down the door of the building, went in and set it on fire. Neighbours of all nationalities, including Georgians, rushed to put the fire out. However, the armed men returned forty minutes later. This time they drove away the neighbours with shots, ringed the building, poured kerosene over it and set it ablaze again. A fire-engine, which came to put out the fire, was not let through.

Frantic telephone calls to the KGB, the police, even the Orthodox bishop, yielded no result. It seemed as though the arson had been officially sanctioned, though no one would ever claim responsibility for it.

Ioannidi arrived at 6am the next morning to find it all gone. When he opened the safe in his wrecked office he believed for a moment that his own unpublished manuscripts had survived, only to see them turn to ashes from the heat before his eyes.

A crowd of curious onlookers gathered. Then the distinguished Abkhaz writer, Shalva Inal-Ipa, walked up stiffly and, observing the ritual of an Abkhaz funeral, bowed his head to the ground.

In a single night Abkhazia's documentary history had been virtually erased. 95% of the archive was destroyed. The only section that more or less survived at all was the radio archive from the 1930s. Nothing from the extensive 19th-century collection was preserved.

The following year, Abkhazia's Communist Party archive, kept in a different building, was annihilated in fighting, as the Abkhaz recaptured Sukhumi from the Georgians. Ioannidi estimates that of 176,000 archival documents in Abkhazia, before the war, 168,000 were destroyed. He ensured that at least some of it survived, for a long time keeping the remaining documents piled at home in his damp ninth-floor apartment, before he was allocated the empty rooms at the university, where the remnant of the archive is now housed.

A legacy Project

It is a truism that combatants in war try to rewrite history. This is a chilling instance where one side succeeded comprehensively in actually destroying the history of its adversary. Part of the struggle between Georgians and Abkhaz is the complaint by the latter that their history was always belittled by their bigger neighbour. But there are multiple ironies here: Abkhazia was a cosmopolitan Black Sea territory with many different nationalities. By erasing the documentation of its rich multi-ethnic past, the Georgians were not only denying the Abkhaz their right to have a history of their own, they were also wiping out the complexity of the real history of this mixed region and sending it back to Year Zero. And of course they also erased themselves.

Nowadays, you would barely know that any Georgians had lived in Sukhumi as traces of their heritage have been removed. And the Greek community of the city, amongst which Ioannidi grew up, has virtually disappeared. What Stalin began and the Georgian warlords continued, the Greek government helped complete by sending a big empty cruise ship to evacuate a thousand Greek citizens from Abkhazia at the end of the war in what they grandly called "Operation Golden Fleece".

Ioannidi stands as a dignified emblem of a multicultural road not taken. He has an unpublished manuscript on the Stalinist deportation of 1949 based on his study of KGB archives that went up in flames. And he has the authority to assert that that mass expulsion deprived Abkhazia of a community which was binding Abkhaz and Georgians together. "If there had not been 1949, the whole situation in Abkhazia would have been different," he told me. "If there had been a neutral force in the middle, war would not have been so possible."

Ioannidi has now formally retired as chief archivist of Abkhazia, although he still spends most of his days there, drinking Greek coffee, casting a fatherly eye over what is left of the institution he ran for forty years. But he is no romantic and wants a younger person to carry on with the job. "I am from the Soviet generation, I am not the best person to know what to do with this now."

The only catalogue perished with the archive itself and Ioannidi would dearly like to see the stacked bundles that remain properly catalogued. But the trouble with being an unrecognised state, he said, is that no one from the outside world offers any help and you live in international limbo, cut off from contact with international archivists.

I am writing this partly in the hope that someone can suggest how to preserve the small charred archive of an inaccessible unrecognised state. It would not be an easy task. But it would be a blow for civilisation in this sad corner of the Caucasus - and a gesture of deserved respect for someone who is a rare curator of decent values as well as of yellowing papers.

Source: openDemocracy