Stanislav Lakoba: "From George Washington to Nestor Lakoba"

Nestor Lakoba (1 May 1893 – 28 December 1936) was an Abkhaz Communist leader.

Elena Zavodskaya - Ekho Kavkaza | This week, the Georgian Service of Radio Liberty published an article on our website about the presentation of "Clientelism and Nationality in Soviet Abkhazia" by American historian Timothy Blauvelt. The goal of the book, as Blauvelt himself writes, is to remove the veil from the mythologized image of the Abkhazian political figure Nestor Lakoba. Abkhazian historian Stanislav Lakoba shared his perspective on this work.

Elena Zavodskaya: Stanislav, Ekho Kavkaza featured a piece by Eka Kevanishvili on Timothy Blauvelt's book-presentation on Nestor Lakoba. Are you familiar with this book, and what are your thoughts on its author, the book itself, and the coverage it received?

Stanislav Lakoba (born 1953) is an Abkhazian historian and politician.

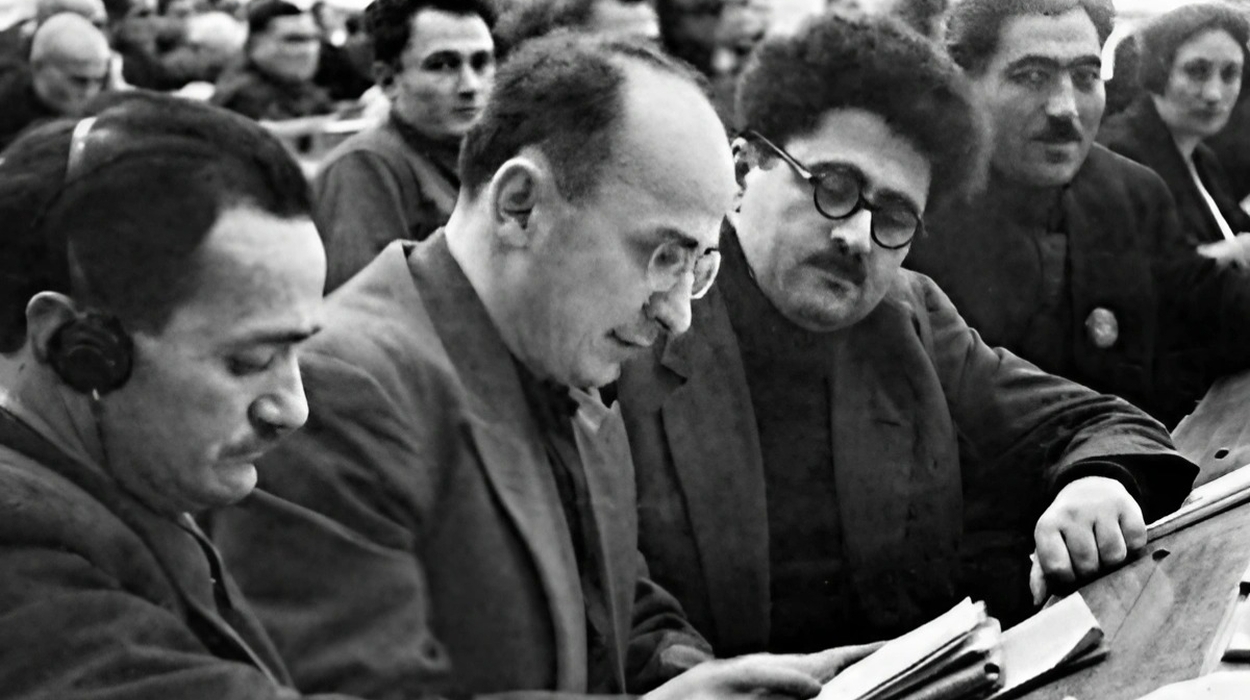

Stanislav Lakoba: To my knowledge, the book was released in 2021 in English and published in both New York and London. It has since been translated into Georgian. Regarding the author, he is an American who resides and works in Tbilisi at Ilia University, focusing on history, thus presenting a Georgian-American viewpoint. The narrative within this book reveals quite a bit. He once reached out to me to help identify some individuals in a photograph. One of these photographs, now featured in the publication, depicts Smetskoj's dacha with Nestor Lakoba, Beria, Vladimir Ladaria, Vasili Lakoba, and others. The book hasn't been published in Russian, making it challenging to fully evaluate, although translations of some parts and individual fragments have been made available. I'm acquainted with some of the materials, but not all. Moreover, this article on Ekho Kavkaza has prompted numerous questions.

- What kind of questions?

- Primarily, these relate to Nestor Lakoba, his circle, and his policies. It appears the author has taken many aspects quite literally, accepting them at face value. Nestor Lakoba's statements, for instance, could vary depending on the expectations of the people and individuals around him. He consistently worked in the interest of Abkhazia, which undoubtedly caused some irritation. It's inaccurate to suggest he had a direct patron or that he was merely a client executing the will of Stalin and others. He was astute and cunning in his approach. He was not a Bolshevik in the strictest sense but rather more of a populist leader, a natural talent. His stance on collectivization, for example, is well documented. He opposed the formation of collectives as they were proposed, a sentiment echoed by the populace. The events of the Duripsh meeting in 1931 are a testament to this. However, the book provides a markedly different interpretation of these events, which is certainly up for debate. He also championed the interests of Abkhazia's multi-ethnic population. Blauvelt, it seems, is only acquainted with a subset of documents and lacks a comprehensive understanding of the entire situation. He also seems to discount the value of eyewitness accounts and memories of those who lived through the era. This wasn't two hundred years ago. These are first-hand accounts from individuals close to Nestor Lakoba, such as Mikhail Lakoba's wife, who spent over 20 years in the camps and later came home. Her insights are invaluable. She shared many details with me. Thus, Nestor was a fundamentally different figure than the one Blauvelt attempts to depict in his work.

- In the discussion about Blauvelt's book, it is mentioned that he utilised the archives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia among other documents. Stanislav, what is your perspective on these archives, which the author employed for his book?

- These documents are well-known and were stored in the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia during the Soviet era. Historians had access to them but often refrained from citing them, not due to inability but because their contentious nature made their intended purpose clear. The documents from the Kadyrov and Tseitlin commissions, compiled during times of internal strife within Abkhazia, aimed at undermining Nestor Lakoba amidst tensions with both internal opposition and external forces dissatisfied with his autonomous governance of Abkhazia, his direct access to Stalin, and his capacity to address numerous issues. This, naturally, was met with discontent from various quarters, including within Abkhazia itself. Such documents surfaced particularly during periods of crisis, notably in 1925, 1929, and 1931, each associated with significant events in Abkhazia's history. I had the opportunity to examine these documents, as well as the archive in America to which Blauvelt refers, where he conducted his research – the Nestor Lakoba Archive. It's my understanding that Musto Dzhik-ogly (Dzhikhashvili) sold it to the Hoover Institution, where these materials, including those from Kadyrov among others, are preserved, thanks to Saria [Lakoba, Nestor's wife].

![On the far left, smoking, is Nestor Lakoba; in the background is Saria Lakoba. Photo by Eugene Schilling. The scene shows the grocery and tobacco trade of Kharlampiy Khristoforovich Ashatidi, [Greek] “Renome”, located on Liberty Street (known as Lenin Street in Soviet times, and today as Leon Street), Sukhum, Abkhazia, 1929. On the far left, smoking, is Nestor Lakoba; in the background is Saria Lakoba. Photo by Eugene Schilling. The scene shows the grocery and tobacco trade of Kharlampiy Khristoforovich Ashatidi, [Greek] “Renome”, located on Liberty Street (known as Lenin Street in Soviet times, and today as Leon Street), Sukhum, Abkhazia, 1929.](/aw/images/archives/abkhazia_1929_nestor_lakoba.jpg)

On the far left, smoking, is Nestor Lakoba; in the background is Saria Lakoba. Photo by Eugene Schilling. The scene shows the grocery and tobacco trade of Kharlampiy Khristoforovich Ashatidi, [Greek] “Renome”, located on Liberty Street (known as Lenin Street in Soviet times, and today as Leon Street), Sukhum, Abkhazia, 1929.

- Are you familiar with these documents?

- Indeed, I am. My book, "Essays on the Political History of Abkhazia," published in 1990, delved into these archives, and I had previously engaged with them in 1983 alongside Ljudmila Malia during our visit to Batumi to study this collection. Malia, who was the director of the Nestor Lakoba Museum, which suffered damage at the war's end and is currently under restoration, collaborated with me. Therefore, my acquaintance with these materials predates Blauvelt's work. Additionally, the esteemed book on Stalin by English researcher-kartvelologist, literary critic, and historian Donald Rayfield, published in 2004 and later in Russian in 2008, offered an objective view that starkly contrasts with Blauvelt's narrative. My interactions with Rayfield about this archive underscored a different perspective, suggesting an information-war aimed at erasing Abkhazia's heroes, leaders, and historical figures. Blauvelt's portrayal, particularly his attack on Saria Lakoba, resorts to slanderous insinuations.

- Stanislav, could you elaborate on the kind of slanderous documents these are?

- Primarily, these were GPU reports crafted to find fault, leading to publications that seemingly even begrudge Nestor and Saria Lakoba their deaths, disturbing their peace posthumously. The intent to tarnish their legacies is palpable. In my view, Blauvelt's narrative is a comprehensive smear-campaign, evident in the chapter-titles, paragraphs, and subtitles derived from these reports. He notably exaggerates, suggesting that directives from Moscow were blindly executed locally. He even quotes Nestor speaking about Stalin, a reflection of the era's complexities that deserves nuanced discussion. Their close relationship is undeniable. Yet, the narrative often overlooks that Nestor Lakoba assumed the role of head of government at 29 and tragically died at 43, placing not just his own but also his family's lives on the altar of Abkhazia. This dedication led to his multifaceted legacy, marked by risk-taking and, ultimately, tragedy. His complex character warrants a more nuanced examination.

- Stanislav, were there any notable responses to this book?

- Certainly, there were several responses, including critical reviews. One notable critique came from George Hewitt, a member of the British Academy and professor at SOAS (University of London), published in 2022. His concise and business-like review offered critical insights, highlighting dissatisfaction with Blauvelt's approach. Hewitt points out Blauvelt's tendency to rely heavily on Party documents and personal correspondences, questioning the credibility of accusations levied against Lakoba over the years. This struggle, marked by Lakoba's strained relations with several secretaries of the Georgian Communist Party and his partial defiance of Party decisions, suggests a nuanced power dynamic rather than a simplistic narrative of patronage and clientelism. There is the well-known 1929 letter if Stalin, where, scolding him, he wrote: ‘Nestor’s mistake is that – we all know – he sometimes does not obey the decisions of the Party, and a second mistake if his is that he does not adopt the Bolshevik position, relying on all layers of the Abkhazian population.’ Lakoba replied: ‘We don’t have a kulak-class, we have no-one to fight with.’ Then there were some things in the letters – in principle, he was dependent on certain structures from the Party, from the Central Committee of Georgia above him, from the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik), and then there were the corresponding services of the GPU, which reported directly to Moscow. All this had to be taken into account.

+ Celebrating a freedom fighter on his 130th birthday: The challenging path of Nestor Lakoba

+ Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him, by Donald Rayfield

+ Excerpt from Timothy K. Blauvelt’s “Clientelism and Nationality in an Early Soviet Fiefdom: The Trials of Nestor Lakoba

+ Stanislav Lakoba: “Thousands of people’s destinies in Abkhazia were crushed”

+ Review of George B. Hewitt & Reply from Timothy K. Blauvelt | Clientelism and Nationality in an Early Soviet Fiefdom: The Trials of Nestor Lakoba

- In Blauvelt's book, there's mention of a letter Nestor Lakoba supposedly sent to Tbilisi following the 1931 peasant-uprising against collectivisation, in which he labelled the rebelling peasants bandits and criminals. How would you respond to this claim?

To put it simply, he effectively saved the people. Force was not used then because even his own mother was among the rebels, facing down machine-gunners, and the situation was peacefully resolved. Beria dared not give the order to fire, avoiding a potential massacre. Moreover, there's testimony from an All-Union Communist (Bolshevik) Party Central Committee instructor, Kozlov, who observed some were ready to tear him apart, reflecting the tense mood. Yet, after Lakoba spoke, the peasants carried him on their shoulders, celebrating him. Kozlov remarked that Lakoba's stance was not in line with Bolshevik ideology, expressing equality among all Abkhazians. This stance displeased some, prompting Kozlov to send a detailed report to Moscow. Many Party officials, supposedly Lakoba's allies, were in fact against him and reported him to the GPU. While a few individuals might have faced repression, the majority of the participants in the Duripsh meeting were dealt with essentially in 1937 already after Lakoba's death. I have documentary evidence of this, such as Suleiman Avidzba from Abgarkhuk, arrested for anti-Soviet activities related to the Duripsh meeting but released by the Abkhazia GPU. Lakoba managed to bring many back, but there were times when he could do nothing. For instance, Kukun Hasanovich Agrba and Vissarion Akhba, both arrested but their fates were sealed differently, with Akhba being executed in 1937. Such cases were numerous and well-known, and blame was later placed on Lakoba. Essentially, he saved as many as he could. Those processed by the Abkhaz GPU typically faced no charges and were released, unlike those arrested by the Georgian GPU, over whom Lakoba had no influence. He helped wherever possible, for example, protecting the noted orator Sit Ebzhnou from Beria's attempts to arrest him. Ebzhnou survived Lakoba and was publicly tried and executed in 1937 under Beria's direct supervision.

Take, Kukun Hasanovich Agrba, of the village Eshera, arrested on 24 February 1931, was released on 19 July 1931. Then Vissarion Akhba, of the village Lykhny, appears throughout the documents as a kulak; he led the “Kiaraz” detachment of 300 people. In 1931 he was arrested but not convicted, and yet he was executed on 10 October 1937. And there are a lot of such examples, as is known. And, by the way, this later served as a charge against Nestor Lakoba. That is, he saved whoever he could. Those who were dealt with by the Abkhazian GPU were, as a rule, not charged and released, but there were others who were arrested directly by the Georgian GPU. And there, of course, Lakoba could no longer do anything. He helped as much as he could. For example, it is known that there was such a one as Sit Ebzhnou, a famous speaker, who spoke loudly there [at the Duripsh gathering]. So, Beria constantly asked that he be arrested, but Lakoba did not allow him to be arrested. And he survived Nestor Lakoba. When there was a public trial of 13 people in the theatre in November 1937, Sit Ebzhnou was there. Neither a Party nor a government figure, he was a peasant, and he was tried there and shot. Moreover, Beria came and personally supervised this trial. These are well-known happenings.

The funeral of Nestor Lakoba | Sukhum, 1 January 1937

- Turning back to George Hewitt's review.

- George Hewitt emphasised the potential impact of Blauvelt's work, questioning how Abkhazians would react if they were to read it. Herein is the comprehensive characteristic, and He poses Blauvelt the question: ‘So, how then do you account for Lakoba’s enduring popularity?’ This was linked to the fact that he was actually poisoned and perished. Blauvelt even tries to deny this, seeming to skirt round it, whereas Donald Rayfield, for instance, explicitly states that Agasi Khandzhian was murdered in Beria's Central Committee office in 1936 and that Lakoba was poisoned, In principle, everyone knew this.

Who was Agasi Khandzhian?

- He was the leader of Armenia, killed right there in Beria's office just months before Lakoba's demise. They wrapped him in a carpet and took him away, bloodied, alleging that he had committed suicide or just died – there were different versions.

Nestor Lakoba (left), Lavrentiy Beria, Agasiy Khandzhian at the party conference, 1935 | © The State Museum of Nestor Lakoba

Do you think Timothy Blauvelt has doubts about Nestor Lakoba's murder?

- Blauvelt leans on the official narrative of a heart attack. However, more significant to me is the perspective of Osip Mandelstam, who commemorated Lakoba's death in poetry. The subsequent persecution of Lakoba's family raises further questions. Why such a fervent search for the archive, now in America, which Blauvelt reviews from the comfort of his office? This archive, preserved at great personal cost, while the donor is now subjected to smears by Blauvelt. For what purpose? Moreover, his comparison of Lakoba to George Washington, amidst the backdrop of current debates over historical memory in America, adds another layer of irony, especially given his critical stance towards Washington.

"The doctors who autopsied the victim were arrested. A month later Lakoba's tomb was flattened and the body exhumed. Lakoba was de-clared an enemy of the people: Saria, his widow, was charged with plotting to kill Stalin with the pistol Allilueva had given her and tortured for two years until she died. Lakoba's mother was bludgeoned to death by Beria's hangman Razhden Gangia. Beria slaughtered almost the entire Lakoba clan, keeping the children in prison until they were old enough to execute. Lakoba's young son Rauf was tortured in Moscow by the notorious Khvat, sentenced to death by Ulrikh and shot in 1941. One brother-in-law and two nieces survived. Most of the Abkhaz intelligentsia perished: Georgians and Mingrelians colonized southern Abkhazia. Beria's revenge was directly sanctioned by Stalin without Ezhov's signature. After Lakoba's murder Stalin stayed away from the Caucasus for nine years."

— from the book 'Stalin and His Hangmen' by Donald Rayfield

- Stanislav, aside from George Hewitt, were there any other significant reactions to this book you're aware of?

- Indeed, Sergey Manyshev, an already renowned even though young historian, offered a very interesting critique in the "Ab Imperio" journal's third issue of 2023. He observed that Blauvelt draws a parallel between the contemporary perception of Nestor Lakoba and the iconic figure of George Washington, describing them both as benevolent national fathers, revered and adored by their people. Manyshev's commentary, laced with sarcasm, questions the simplification of Lakoba's legacy, suggesting a more complex reality. This underscores the concern with Blauvelt's lack of critical engagement with his sources. Blauvelt relies heavily on documents from the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the GPU archives, which were influenced by Beria's well-documented animosity towards Lakoba. Manyshev criticises the author for basing several chapters on detailed scrutiny of denunciations against Lakoba, implying that such accusations shaped the entirety of Abkhazia's history during the era. This approach raises doubts about the reliability of Stalin-era official documents and the legitimacy of the accusations against Lakoba, suggesting they may merely reflect the era's power-struggles. Manyshev regrets Blauvelt's omission of a deeper investigation into Lakoba's death, merely touching upon the "mythological" aspects such as the infamous dinner at Beria's. The absence of a critical examination of such a pivotal event leaves a gap in understanding the intricacies of Soviet governance. Manyshev sums up that the study's conclusions were likely swayed by its reliance on Georgian archives, lamenting the missed opportunity to incorporate Russian archival materials. He acknowledges Blauvelt's role in bringing Lakoba's story out of undeserved obscurity, yet implies the narrative was inadvertently skewed by its source-material. This is a sentiment I echoed in my own review upon the book's release in 2021, highlighting the problematic reliance on denunciatory documents, a practice even Georgian historians avoided due to their contentious nature.

Blauvelt contends that in modern Abkhazia, Lakoba is mythologised, his tenure idealised as a lost utopia disrupted by Beria and his ilk. He suggests his book's greatest contribution could be demystifying the historical narrative. However, it appears he has instead enshrouded it in a new mythos, predicated on denunciations. This approach fails to acknowledge the deep-seated reverence for Lakoba and Saria, whose legacies transcend mere historical record. Consider the poem "Nestor and Saria" by Semjon Lipkin, penned from the accounts of those personally acquainted with Lakoba. This isn't distant history but the lived experiences of individuals closely connected to the events. Lipkin's verses capture the essence of Lakoba's bond with his people and his nuanced leadership:

He cherished all within his simple fold,

The customs and epics of old,

Freeing them to live as they might,

Preserving their legacy in the light.

Reluctant was he to displace,

A rare few faced a harsher fate,

Only when no other path was clear,

Did he act, guided by his steadfast care.

Abkhazia, his unwavering charge,

Navigating complexities large,

Sometimes bending truth's arc,

For Abkhazia, he left an indelible mark.

It is this nuanced portrayal, rooted in the authentic experiences and memories of those who lived through the era, that cements Lakoba's enduring legacy.

This article was published by Ekho Kavkaza and is translated from Russian.